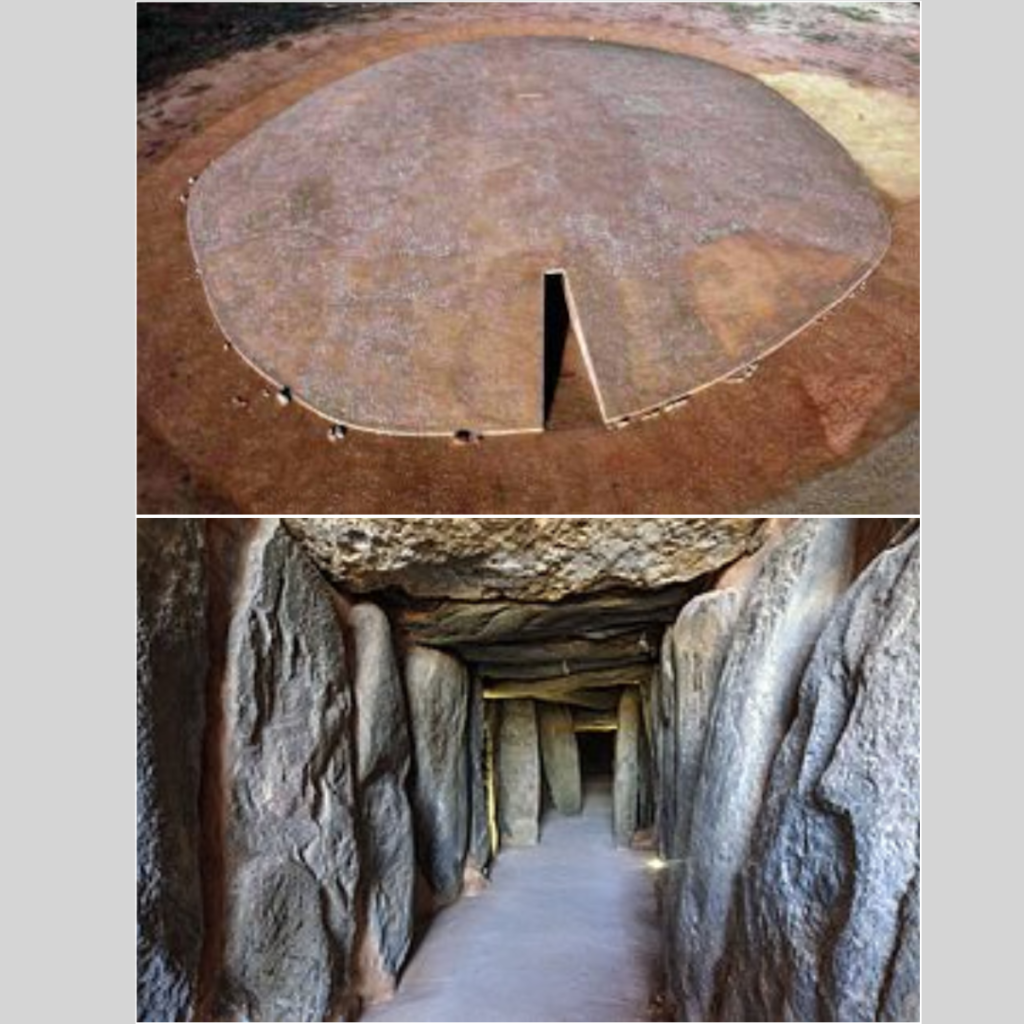

The Dolmen de Soto from above, showing both the low earth mound covering the megalithic corridor, and the reconstructed entrance way beside the portal, which provides access to the interior. (Image: Dron Pelayo)

Investigating an isolated Neolithic tomb in Andalucía has revealed a new dimension to its rock art. What can this tell us about life as well as death in a remarkable megalithic monument? George Nash, Sara Garcês, José Julio García Arranz, and Hipólito Collado share the secrets of the Dolmen de Soto.

The origins of Neolithic tomb building in Europe are difficult to pinpoint. We know that the Neolithic Revolution occurred in the ‘Fertile Crescent’ of the Middle East around 10,000 BC, but the development and spread of tomb architecture across Europe is less clear. We can say that during the 5th and 4th millennium BC, passage graves became dominant, probably after emerging from a tomb style popular in eastern Europe. It appears that the passage-grave tradition originally arose in the Iberian Peninsula, before becoming part of a Neolithic package that moved northwards, transmitting the architectural style to most of the core areas of Atlantic Europe, which included portions of modern-day Portugal, north-west Spain, Brittany, the Channel Islands, south-east Ireland, southern Scandinavia, and, to a limited extent, north Wales, north-west England, Scotland, and Orkney.

Inside the Dolmen de Soto. Recent survey of the rock art within this passage grave has revealed a previously unknown element, raising questions about just who could enter this remarkable structure. Here we see the tomb passage, as viewed from the chamber area.

When viewing these tombs from the outside, the most immediately obvious feature of a generic passage grave is a round mound, containing an entrance leading into a subterranean corridor, which is typically orientated east–west. This is the eponymous passage, and it usually merges or connects with a defined burial chamber. In the case of the Dolmen de Soto, its passage and chamber appear to form a continuous gallery, which constricts halfway along its course. At some stage, various stone uprights lining the passage and chamber were engraved with megalithic art, which was accompanied by painted schematic images. In one case, this artwork came courtesy of a reused menhir, but most examples seem to have been created either while construction was under way, or more likely when the tomb was in use. As part of a Junta de Andalucía-funded project, a Portuguese-Spanish-British team was commissioned to record this unique prehistoric artistry in 2016 and 2017.

Establishing a baseline

The passage-grave tradition within this part of the Iberian Peninsula appears to emerge around the 4th millennium BC. Its roots probably lie in converging architectural ideas that grew up around concepts of annual celestial or life/death cycles. Such monumental tombs were also a way to honour the dead and probably even a means to signal status within a community based on varying degrees of access to the burial place. This architectural movement, along with burial practices and grave goods that differ from region to region, appears to have enjoyed widespread popularity for at least two millennia, over the course of which the tradition evolved considerably, with changing styles, morphology, size, and probably use.

Archaeological research into prehistoric monuments in Andalucía spans some 180 years. From the mid 19th century onwards, numerous Neolithic burial sites were excavated, including plenty of passage graves in eastern Andalucía, which form what is known as the Los Millares group. Unfortunately, these sites were investigated before the advent of systematic archaeological excavation and scientific-dating methods, leaving the regional chronological sequence difficult to determine.

Despite these early shortcomings, by the latter part of the 20th century, fieldwork and research had identified the existence of distinct monument groups within Andalucía, which had become firmly established as one of southern Europe’s largest and most-concentrated core areas of Neolithic burial activity. Since the early part of this century, more specific site-led research has been undertaken on a number of monuments, including urgent consolidation and conservation work at the Dolmen de Soto. Our recording of the rock art came about as part of this programme.

A rather splendid type of architecture

The Dolmen de Soto is one of around 1,650 Neolithic burial monuments within the region of Andalucía. The province of Huelva alone boasts around 210 burial-ritual monuments displaying various architectural styles, which can typically be sorted into distinct clusters. In this regard, the Dolmen de Soto stands alone, as an essentially isolated monument lying north of the Tinto River. The tomb is dated to between 3000 and 2500 BC, placing it within the later stages of the passage-grave tradition and making it broadly contemporary with, say, the larger examples within the Boyne Valley in Ireland and two passage graves in north Wales. It is more than likely that a similar date can be applied to the majority of the 200 or so monuments that stand within Huelva, making them a comparatively late flourishing of the passage-grave tradition that took root elsewhere in the Iberian Peninsula a millennium or so earlier.

Within the tomb, the east–west passage and chamber collectively measure about 21m in length and were each created using a series of stone uprights. The north wall required 31 of these, while a further 33 went into the southern side; together, these walls support 20 large capstones. Part of this capstone roof had been removed from the chamber prior to Obermaier’s excavation. The passage and chamber are set within a low mound, about 4m high and 75m in diameter. In terms of geology, the team identified that the vast majority of the uprights were a form of hard sandstone known as greywacke, set alongside several limestone and quartzite examples.

Careful thought seems to have gone into the design of the passage and chamber. Although the entrance is comparatively narrow, at just 0.8m wide, the breadth of the passage increases as one processes to the chamber, which is 3.1m wide. Such increasingly generous dimensions are reflected in the height of this corridor, as it rises from c.1.55m at the entrance to c.3.9m at the eastern end of the chamber. Graduating the height and width in this manner allows ‘visitor(s)’ to move from the entrance into the passage and then the chamber with relative ease. At the same time, however, any viewers watching from outside the tomb would find it difficult to see into the chamber.

Art gallery

Prior to the survey, the team carefully considered the potential impact of our recording techniques on the archaeology, and how the results should be archived. It was especially important to keep any contact between the researcher and the rock-art surface to a bare minimum. The photographic survey provided detailed coverage of all 64 upright stones forming the interior walls, as well as the roofing slabs they supported. Although many of the engraved stones had been recorded in the past, our work identified previously overlooked examples of rock art. The photogrammetry survey provided an accurate account of all engravings, however faint they were.

A view of the pitted surface of Stone 15 when D-stretch is employed, making traces of haematite visible as red splodges,

A view of the pitted surface of Stone 15 when D-stretch is employed, making traces of haematite visible as red splodges,

One of the most important items within our toolkit was lighting. Unsurprisingly, both the passage and chamber are naturally dark places. In order to identify and record the wealth of engravings present, oblique lighting proved invaluable for illuminating even barely visible engravings. It also assisted in the photogrammetry and animation project, where an ability to control the angle of the light source was once again essential. To provide an accurate record of these markings, our survey employed a variety of techniques that are now standard practice in rock-art research, particularly photogrammetry and Decorrelation-Stretch (also known as D-Stretch). This latter technique employs software initially developed by NASA, which has proved ideal for digitally enhancing faint traces of ancient painting.