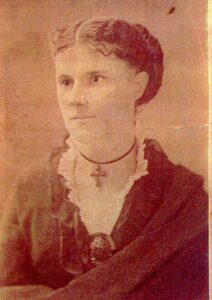

Mary Loughborough was the publisher of the Little Rock, Arkansas–based Southern Ladies’ Journal. When she died at the age of fifty, she was buried alongside her husband in Mount Holly Cemetery in Little Rock.

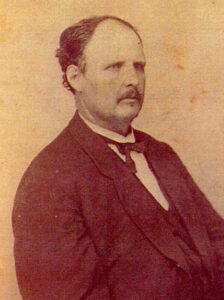

She was born in New York on August 25, 1837, and raised in St. Louis, Missouri. In 1859, she married prominent attorney James Loughborough. The couple would have six children.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861 and Missouri split over secession, James enlisted in the Missouri State Guard, moving with it to Arkansas, to Tennessee, and then to northern Mississippi, where he served in several major battles and in General Ulysses S. Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign. Mary followed her husband—literally—with a child in tow. Letters she wrote reveal that she was first in Memphis, then in towns all over northern Mississippi, and ultimately Jackson. “I am unlucky enough to be identified with some retreat or threatened city,” she wrote of managing to stay ahead of Grant’s unsuccessful 1862 invasion of the state.

After the war, James became the land commissioner of the Cairo and Fulton (later Union Pacific) Railway. The town of Hope, Arkansas, was named for their daughter, Hope. The Loughboroughs would ultimately settle in Little Rock.

A widow by the 1880s, in 1881 Mary launched the Ladies’ Little Rock Journal as an insert in the Rural and Workman newspaper. It grew to become the standalone Arkansas Ladies’ Journal and finally the Southern Ladies’ Journal. The publication was a major new departure for the South, as it featured not only women’s domestic interests but also took a stand on women’s right to vote. The voting efforts are detailed in my book Arkansas Women and the Right to Vote: The Little Rock Campaigns, published by Butler Center Books in 2015.

In early 1887, Mary was planning to enlarge the newspaper and issue it twice monthly, but in February she took seriously ill and died on August 27. The following day, the Arkansas Gazette called her “a much respected and talented woman” whose friends would greatly miss her.

In early 1887, Mary was planning to enlarge the newspaper and issue it twice monthly, but in February she took seriously ill and died on August 27. The following day, the Arkansas Gazette called her “a much respected and talented woman” whose friends would greatly miss her.

***

Though little else is known about her, Mary Loughborough was obviously a well-educated and accomplished individual. If pioneering the publication of a newspaper for women—the first women’s newspaper in the South—had been all that she had done, she would have secured a place in history. But nearly twenty years before, she had also written and published an account of her experiences in Vicksburg in 1863. Called My Cave Life in Vicksburg, it is acclaimed as the best account of the civilian experience in the besieged city. First published in New York by Appleton in 1864, it is available online courtesy of Project Gutenberg, and many recent printings are available.

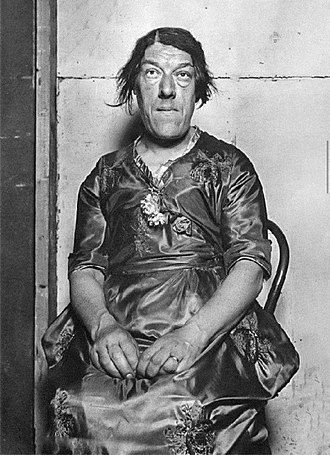

Mary’s letters of her sojourn through northern Mississippi, appended at the end of her tale, deal with her journeyings and experiences in 1862. But this was only the beginning of her trials. Having arrived in Jackson in late 1862 and remaining there in April 1863, she visited Vicksburg with friends, only to arrive at the time of the momentous bombardment on April 16 of Admiral David Porter’s gunboats and transports as they sneaked past the thirteen riverfront batteries of the city to meet Grant’s army and transfer Union troops across the river. Her trip lasted several horrifying days.

She wrote:

I shall never forget my extreme fear during the night, and my utter hopelessness of ever seeing the morning light. Terror stricken, we remained crouched in the cave, while shell after shell followed each other in quick succession. I endeavored by constant prayer to prepare myself for the sudden death I was almost certain awaited me. My heart stood still as we would hear the reports from the guns, and the rushing and fearful sound of the shell as it came toward us.

“We were glad to leave Vicksburg,” she further wrote, “with the sound of the cannon and noise of the shell still ringing in our ears.”

But on returning to Jackson her odyssey continued. She had to abandon Mississippi’s capital city around May 12, 1863, on one of the last trains going west before Grant’s army destroyed the railroad at Clinton and then overran Jackson. By the time she arrived in Vicksburg for the second time, the river city was the end of the line, for with Grant’s incursion into Louisiana in March 1863, the railroad to the west was blocked. Escape was impossible, but the good thing was that her captain husband was stationed there.

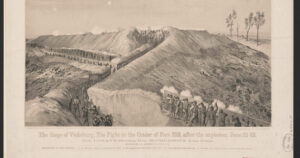

The siege effectively began on May 17, 1863, when General William T. Sherman’s XV Corps of Grant’s Army of the Tennessee arrived outside the northern section of Vicksburg’s formidable fortifications.

Union forces now surrounded the town. Cannon and gunboats on the Louisiana side of the Mississippi river bombarded from the west. Below Vicksburg’s landward defenses, 220 cannon bombarded from the east. Mary was stuck in the middle.

She wrote:

On one occasion, I was reading in safety, I imagined, when the unmistakable whirring of Parrott shells told us that the battery we so much feared had opened from the entrenchments. I ran to the entrance to call the servants in; and immediately after they entered, a shell struck the earth a few feet from the entrance, burying itself without exploding. I ran to the little dressing room and could hear them striking around us on all sides. One fell near the cave entrance, and a servant boy grabbed it and threw it outside; it never exploded.

She was describing only one of the eighty-nine batteries that the Union forces quickly installed around the city’s fortifications. With the bombardments continuing fierce and relentless, Vicksburg’s inhabitants dug caves in the stable hills of loess soil for safety. Mary’s cave was in town.

She wrote:

She wrote:

And so I went regularly to work, keeping house under ground. Our new habitation was an excavation made in the earth, and branching six feet from the entrance, forming a cave in the shape of a T. In one of the wings my bed fitted; the other I used as a kind of a dressing room…

Her husband communicated with her daily and came to see her once a week. Later, he moved her to a new cave. To get there, they drove out of town toward the battle lines and close to “two large forts on the hills above us,” where she was installed in one of the little “shell and bomb-proof houses in the earth, covered with logs and turf.”

She reminisced:

Our little home stood the test nobly. We were in the first line of hills back of the heights that were fortified; and, of course, we felt the full force of the very energetic firing that was constantly kept up; and being so near, many that passed over the first line of hills would fall directly around us.

Mary relates many acts of bravery and many others of tragedy. Her tale is replete with descriptions of terrible beauty and of such pathos they raise a lump in the throat. She captures the hell on earth that both the townspeople and the men on the siege lines were living through—at the same time as the breathtaking beauty of a moonlit sky revealed an alternative dimension to being. Frequently commenting on the evil around her, she still expresses her faith in God. Though her book was written later, she captures the immediacy of her experiences, feelings, and thoughts as if in real time.

And so life in Vicksburg would continue, but with ever-diminishing food supplies and with death and disease all around. Even with hunger, deteriorating morale, and increasing illness among the Confederate soldiers, and with Grant’s troops digging ever closer and pummeling constantly at the fortifications, the siege lasted forty-seven days.

And so life in Vicksburg would continue, but with ever-diminishing food supplies and with death and disease all around. Even with hunger, deteriorating morale, and increasing illness among the Confederate soldiers, and with Grant’s troops digging ever closer and pummeling constantly at the fortifications, the siege lasted forty-seven days.

On July 4, 1863, General John C. Pemberton surrendered the city to Grant. The Union took control of the Mississippi River and paroled the Confederate army. While Grant gave passes to some women to return to their home state, Mary does not say how she got out of Vicksburg.

Soon, however, friends in St. Louis heard of her harrowing entrapment in the river city during the siege that took place 160 years ago this year. They encouraged her to write about it. And in 1864 Mary’s memoir was published, to become a bestseller, still available today. It is an amazing legacy from a woman who made Little Rock her home.

***

On March 3, 1888, a year after Mary’s death, another new women’s venture, the Woman’s Chronicle, reported that the Southern Ladies’ Journal had died with Mary. But its legacy still lives on in the twenty-first century as a document of women’s lives in the nineteenth-century South. Microfilmed Journal issues are available at the Arkansas State Archives (ASA) in Little Rock. The Arkansas State Archives started the Arkansas Digital Newspaper Project (ADNP) in 2017 to digitize historic Arkansas newspapers from microfilm held at ASA. The ADNP is part of the National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP), a partnership with the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America project with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). View the Chronicling America page for the Southern Ladies’ Journal here.