“If the Wildcat lagged behind the Zero in performance, why did it enjoy such success?”

By Marc Liebman

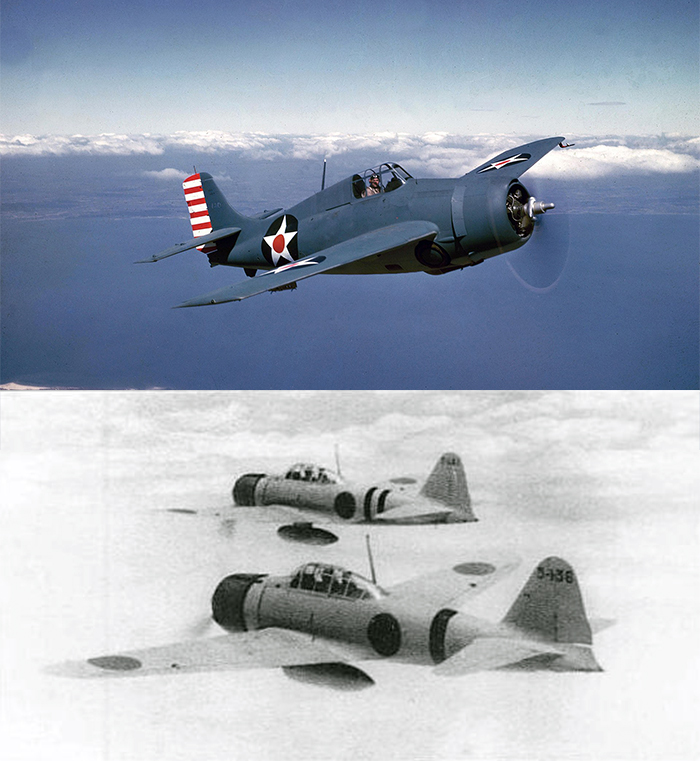

WHEN THE UNITED States Navy entered the war with Japan, it did so with the Grumman F4F Wildcat as its principle frontline carrier-based fighter – a warplane that, at least on paper, was greatly outclassed by Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero. The actual numbers tell a different story.

Unable to beat the Zero’s top speed of 330 mph and less maneuverable than its Japanese counterpart, the stubby, ungainly Wildcat managed to prevail in the face of the superior enemy fighters it went up against in the war’s first months.

Consider the Battle of the Coral Sea. During the May 4 to 8, 1942 clash off the Solomons, U.S. Navy Wildcats shot down 14 A6Ms for a loss of just 10 aircraft.

Later that year – between Aug. 7 and Nov. 15 – Wildcats shot down 72 Zeros while losing 70. And, in the carrier vs. carrier battles during the same period, 43 Zeros were bagged at a cost of 31 Wildcats.

The numbers kept improving in the Grumman fighter’s favor. By the end of the Battle for Guadalcanal – Feb. 3, 1943 – records show that Navy and Marine Corps aviators flying F4Fs shot down 5.9 Zeros for every one Wildcat lost. That ratio would eventually grow to 6.9:1.

So, if the F4F Wildcat lagged behind the Zero in performance, why did it enjoy such success?

Origins

The Wildcat was born out of 1936 U.S. Navy requirement for a new monoplane fighter. Grumman entered the competition with the F4F-2, an aircraft that had originally been conceived as a biplane with retractable landing gear. Problems with the plane’s Pratt & Whitney R-1830 engine plagued prototypes and the Navy instead opted for the Brewster F2A Buffalo. In the meantime, France had expressed interest in the new Grumman monoplane and ordered 81 in 1940. Deliveries were halted when the country fell to the Nazis in May of 1940; Great Britain took over the contracts, designating the plane the Martlet Mk. I. One of these airplanes scored the first Wildcat/Martlet kill when on Christmas Day, 1940, a Martlet I shot down a German Ju-88 over Scapa Flow.

Grumman continued to improve the F4F and by 1941 the U.S. Navy was placing orders for Wildcats to replace its Buffalo squadrons, which were already proving to be obsolete.

On the other side of the Pacific, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) was in the market for a fast, modern fighter to replace its fixed gear, open cockpit Type 96 fighters (Allied code name Claude). Development of what became the Zero began in 1936 with an emphasis on maneuverability, long range and rate of climb.

Japanese aeronautical engineers went to great lengths to ensure the new airplane was as light as possible, yet strong enough to survive carrier operations. Researchers at the Sumitomo Metal Company created Extra Super Duralumin alloy, which was stronger, lighter and easier to fabricate than what was being produced in the rest of the world.

The first A6M prototypes were turned over to the IJN in September 1939 and production orders followed in July 1940. Zeros first saw combat in China where their sudden appearance and outstanding performance gave the American Volunteer Group (the “Flying Tigers”) a shock.

Strengths and Weaknesses

Designed for aerobatics at medium altitudes –15,000 feet – the Zero was the ideal airplane for Japanese pilots, who had been trained to focus on air-to-air maneuvering and fighting spirit.

Gunnery was also important, but the IJN pilots believed that between their aerobatic skill, the Zero’s maneuverability and esprit de corps, they could outfly any enemy.

In the U.S. Navy, training focused on gunnery, specifically deflection shooting – the practice of estimating the lead needed to hit a moving target. This skill, along with aerobatics, would pay huge dividends in the coming air battles.

By the Battle of Midway, U.S. Naval aviators had learned that the Zero was a formidable opponent. The Japanese fighter had a lower wing loading and a better horsepower-to-weight ratio, which translated into better climb rates and tighter turns.

But the Zero was only marginally faster than the Wildcat below 18,000 feet. Depending on the source, the difference in speed was as much as 20 mph or as little as 13. Even a 20-mph advantage won’t outrun bullets.

Naval aviators put the Wildcat’s strengths to good use. Diving away was one edge the F4F had over the Zero. Above 280 mph, the A6M’s controls stiffened noticeably and above 300 mph rolling the airplane was difficult. In such settings, its large control surfaces were actually liability. Above 350 mph, the Zero’s elevators and ailerons were almost impossible to move. The F4F had none of these problems because servo tabs on all the control surfaces countered aerodynamic forces.

Furthermore, the traditional two-barrel carburetor on the Zero’s Nakajima Sakae engine starved the engine for fuel whenever the Zero pilot shoved the nose down abruptly or flew upside down. Fuel flow was disrupted and the engine would cut out until positive G’s were restored.

The Wildcat’s engine had a pressure injection carburetor which didn’t care what attitude the airplane was in. It also featured a two-stage supercharger that gave more boost at higher altitudes than the single-stage unit on the Zero. This enabled F4F pilot to dive, turn enough to shoot and dive away.

While the Zero had a significantly longer range than the Wildcat, in a dogfight this is insignificant unless one pilot was low on fuel and if he didn’t leave the fight, would not make it home. However, what proved far more important was how the fuel was stored in both airplanes.

The Zero carried a total of 140 gallons fuel distributed between a small fuselage tank and one in each wing. An 85 gallon drop tank could be carried on a fuselage centerline station. The Wildcat carried all its internal fuel in one 166-gallon tank in the fuselage just aft of the landing gear. Later models could carry two 58 gallon drop tanks under the wings.

To minimize weight, the Zero’s tanks were essentially vented boxes sealed to prevent leakage. As the plane burned fuel, highly explosive fuel vapours accumulated in the tank. Any puncture by a tracer or incendiary round could ignite the fumes.

Behind the pilot, the F4F featured a large plate of case-hardened steel that could stop .50 caliber bullets. Plus, the front panel of the windscreen could absorb .30 caliber bullets. The Zero had no armour of any kind. Hits by .50 caliber rounds would rip through the fuselage’s thin alloy and into the cockpit often killing the pilot instantly.

The Zero Model 21 did pack a punch. It was armed with two 20-mm cannon with 60 rounds per gun and two 7.7-mm machine guns with 500 rounds. Until the Japanese increased the number of cannon rounds to 100, the Zero pilot had less than 10 seconds of 20-mm ammunition. F4F-4s on the other hand, were armed with six, .50 caliber Browning M-2 guns that fired around 750 rounds/minute and carried 240 rounds per gun.

Despite the Zero’s heavy 20-mm cannon, the Wildcat’s “broadside,” i.e. the weight of lead being fired was actually greater per burst than that discharged by the Zero. Plus, the Japanese pilot had to deal with the very different trajectories of the 7.7mm and 20mm rounds, which made targeting a challenge.

Lessons from First Combat

Zero pilots, many of whom were air combat veterans from years of war in China, flew a modified three-plane V, with one wingman high and to the right and another off to the left, also higher. The element leader was the “shooter” and the other two pilots were to protect the leader. Conversely, U.S. Navy fliers, who had no combat experience, applied the lessons of European air combat, and shifted from the three-plane V to two-plane elements and four-plane divisions in what is known today as the “finger four” formation.

Dogfights over the Pacific very quickly devolved into what is known as 1V1 or one vs. one. As such, the integrity of three-plane V was very difficult to maintain. On the other hand, the two-plane element was much easier to continue through a fight.

American pilots Jimmy Flatley and John Thatch began experimenting with these tactics during the Gilbert and Marshall Island Raids of February, 1942 and the Battle of the Coral Sea. The Thatch Weave, a maneuver in which two aircraft or two elements criss-cross their paths. When an enemy plane engages one of the aircraft in the formation it leaves itself open to attack by the other. Even though the aircraft losses were about equal during these early dogfights, Thatch and Flatley drove a change in tactics to the weave, coupled with the dive, shoot, and dive away doctrine.

The Wildcat Advantage

As the war progressed, pilots flying the F4F began to have their way with the Zero. Weapons and tactics were only part of the equation.

Improvements in U.S. Navy radar direction enabled Wildcat pilots to take advantage of the plane’s better performance at high altitude and dive down onto the Japanese formations.

Training was another element. The U.S. Navy quickly realized its pre-war emphasis on gunnery was paying off and combat experienced leaders were pulled from the frontlines and sent back to training squadrons to teach their hard-learned lessons. Thus, rookie U.S. Naval Aviators flying the F4F had a decided advantage when entering combat.

In the IJN, pilot training deteriorated as the war progressed. U.S. submarines savaged Japanese shipping traffic, which meant there was less fuel for flight schools and fewer raw materials to build airplanes. Rather than recycle experienced pilots into training squadrons, IJN fliers stayed at the front until they were either killed or incapacitated. Once the experienced cadre from early in the war was decimated at Midway and in the skies over Guadalcanal, the quality of the average IJN pilot dropped significantly.

By 1943, experience levels of the pilots fighting for each side were reversed: the experience level of the U.S. Navy squadrons outstripped the Japanese.

Coupled with the Wildcat’s ability to absorb damage and bring the pilot home, the results were predictable. At the Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway, the exchange ratio between Zero and Wildcat was a draw. By the time the Battle for Guadalcanal was over, the tide had shifted in the F4F’s favour. As the war progressed, just kept improving and ultimately became almost seven to one.

Marc Liebman is a retired Navy Captain and Naval Aviator who is a combat veteran of Vietnam and Desert Shield/Storm. He is also an amateur historian and award-winning author with nine novels in print.