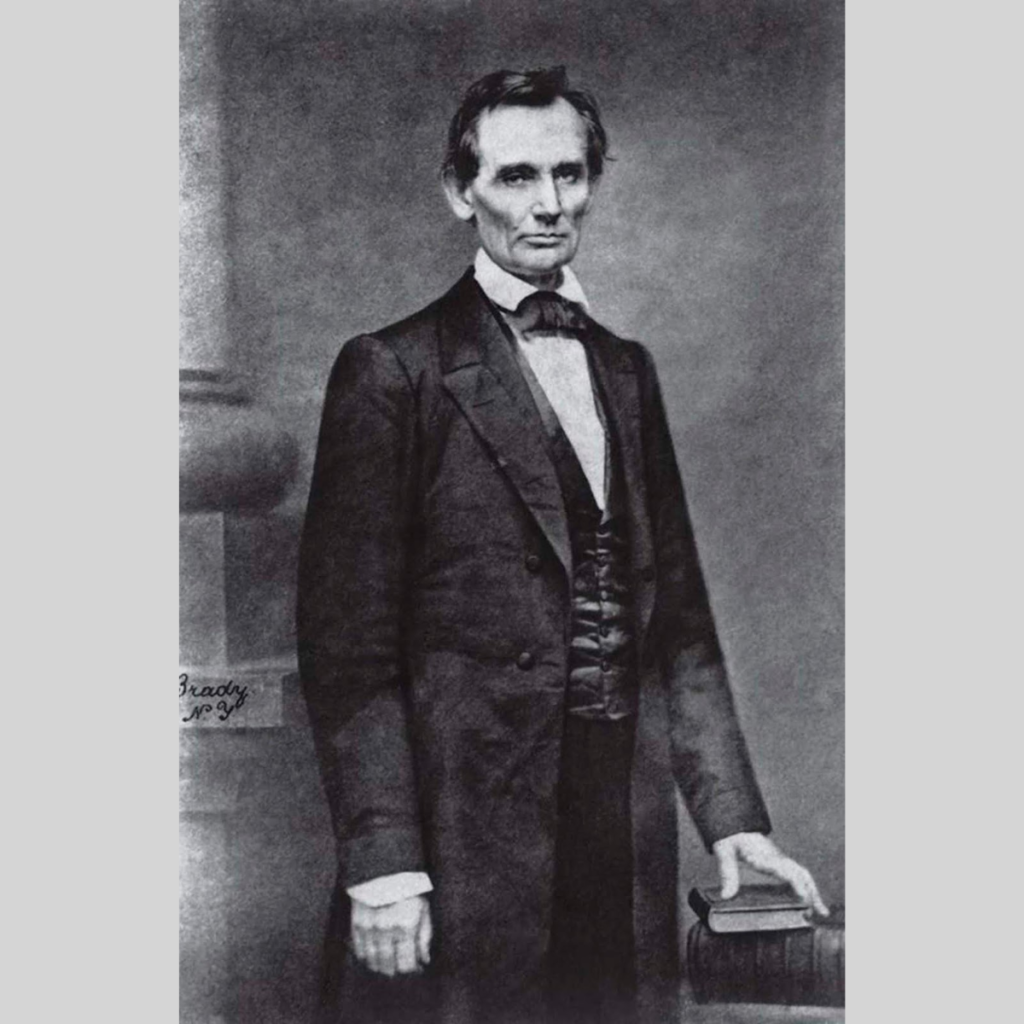

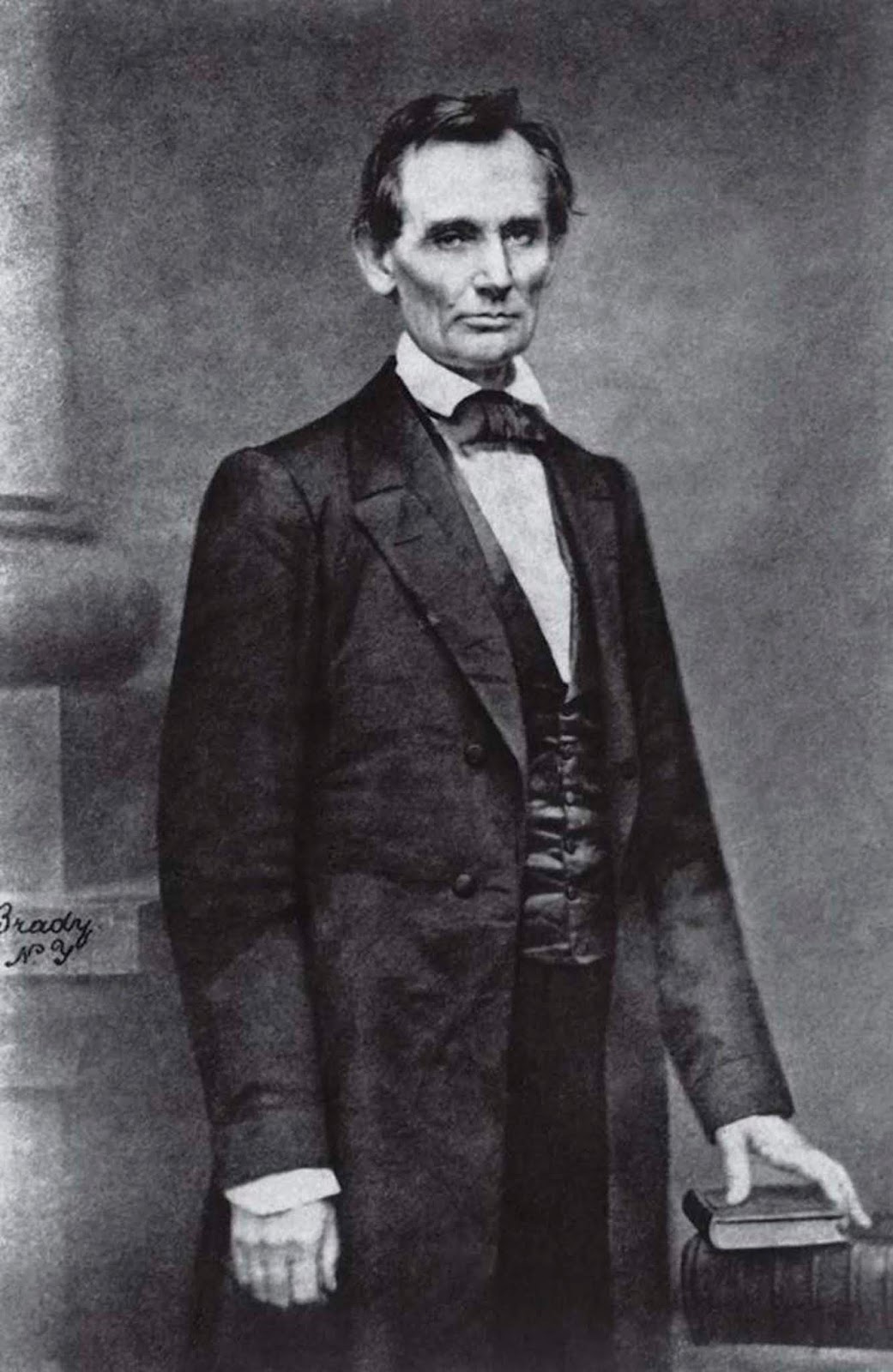

Abraham Lincoln was a little-known one-term Illinois Congressman with national aspirations when he arrived in New York City in February 1860 to speak at the Cooper Union.

Abraham Lincoln was a little-known one-term Illinois Congressman with national aspirations when he arrived in New York City in February 1860 to speak at the Cooper Union.

The speech had to be perfect, but Lincoln also knew the importance of image. Before taking to the podium, he stopped at the Broadway photography studio of Mathew B. Brady.

The portraitist, who had photographed everyone from Edgar Allan Poe to James Fenimore Cooper and would chronicle the coming Civil War, knew a thing or two about presentation. He set the gangly rail splitter in a statesmanlike pose, tightened his shirt collar to hide his long neck and retouched the image to improve his looks.

In a click of a shutter, Brady dispelled talk of what Lincoln said were “rumors of my long ungainly figure … making me into a man of human aspect and dignified bearing.”

By capturing Lincoln’s youthful features before the ravages of the Civil War would etch his face with the strains of the Oval Office, Brady presented him as a calm contender in the fractious antebellum era.

Lincoln’s subsequent talk before a largely Republican audience of 1,500 was a resounding success, and Brady’s picture soon appeared in publications like Harper’s Weekly and on cartes de visite and election posters and buttons, making it the most powerful early instance of a photo used as campaign propaganda.

As the portrait spread, it propelled Lincoln from the edge of greatness to the White House, where he preserved the Union and ended slavery. As Lincoln later admitted, “Brady and the Cooper Union speech made me President of the United States.”