A French SPAD S.XVI two-seat biplane reconnaissance aircraft, flying over Compeign Sector, France ca. 1918. Note the zig-zag patterns of defensive trenches in the fields below.

Aerial warfare was by no means a First World War invention. Balloons had already been used for observation and propaganda distribution during the Napoleonic wars and the Franco-Prussian conflict of 1870-1871.

Planes had been used for bombardment missions during the Italo-Turkish War of 1911-1912. Yet, aerial warfare during the First World War marked a rupture with these past examples. It was the first conflict during which aircraft were involved on a large scale and played a significant role.

At the beginning of the war, the usefulness of air machines was met with a certain amount of skepticism by senior officers on all sides. In fact, airplanes were mostly involved in observation missions during the first year of the conflict.

However, rapid progress enhanced airplanes’ performance. In 1915, the Dutch aircraft manufacturer Anthony Fokker, who was working for the Germans, perfected a French invention allowing machine-gun fire through the propeller.

This discovery had a revolutionary consequence: the creation of fighter aircraft. This type of plane gave an edge to the Germans during 1915.

German pilot Richard Scholl and his co-pilot Lieutenant Anderer, in flight gear beside their Hannover CL.II biplane in 1918.

Their air superiority was to last until April 1916, two months after the beginning of the battle of Verdun. Thereafter, Allied dominance was gained through the creation of French fighting squadrons and the expansion of the British Royal Flying Corps.

The control of the sky was to change hands again in the first half of 1917 when the Germans reformed their squadrons and introduced modern fighters. During April 1917, nicknamed ‘bloody April’, the British suffered four times more casualties than the Germans.

But things were on the move on the Allied side. Successful reorganizations in France and Britain brought back air control for good until the Armistice.

During 1915, another important step was taken when the Germans organized strategic bombing over Britain and France by Zeppelin airships. In 1917-18 ‘Gotha’ and ‘Giant’ bombers were also used.

This new type of mission, targeting logistic and manufacturing centers, prefigured a strategy commonly adopted later in the century. Inevitably, bombardments of ports and factories were quickly adopted by all sides and led to civilian deaths.

British Handley-Page bombers on a mission, Western Front, during World War I. This photograph, which appears to have been taken from the cabin of a Handley-Page bomber, is attributed to Tom Aitken. It shows another Handley-Page bomber setting out on a bombing mission. The model 0/400 bomber, which was introduced in 1918, could carry 2,000 lbs (907 kilos) of bombs and could be fitted with four Lewis machine-guns.

Although the number of civilians killed by aerial machines remained small during the war, these air raids nonetheless caused widespread terror.

Yet, planes were on occasions a welcome sight. Indeed, aircraft and balloons were used by the Allies from 1915 to 1918 to drop propaganda leaflets over occupied France, Belgium, and Italy in order to combat German psychological warfare. Propaganda was also dropped on German soldiers in an attempt to demoralize them.

In 1915, aviation caught the attention of the press both in Germany and in the Allied countries. Fighting pilots credited with at least five victories became known as ‘aces’ and were admired as celebrities on Home Fronts until the end of the conflict.

This phenomenon illustrates the ability of war culture to penetrate all aspects of society but also underlines a paradox: heroes of the air became glamorous because they were clean and deemed noble while their infantry counterparts remained an anonymous mass, stuck in the mud of the trenches. This romanticized admiration by the public of flying aces was a cause of tension and jealousy between army and air force.

German soldiers attend to a stack of gas canisters attached to a manifold, inflating a captive balloon on the Western front.

By the war’s end, the impact of air missions on the ground war was in retrospect mainly tactical – strategic bombing, in particular, was still very rudimentary indeed. This was partly due to its restricted funding and use, as it was, after all, a new technology.

On the other hand, the artillery, which had perhaps the greatest effect of any military arm in this war, was in very large part as devastating as it was due to the availability of aerial photography and aerial “spotting” by balloon and aircraft.

Tactical air support had a big impact on troop morale and proved helpful both to the Allies and the Germans during 1918 when coordinated with ground force actions.

But such operations were too dependent on the weather to have a considerable effect. Meanwhile, fighting planes had a significant impact in facilitating other aerial activities.

Aviation made huge technological leaps forward during the conflict. The war in the air also proved to be a field of experimentation where tactics and doctrines were imagined and tested.

A German Type Ae 800 observation balloon ascending.

A captured German Taube monoplane, on display in the courtyard of Les Invalides in Paris, in 1915. The Taube was a pre-World War I aircraft, only briefly used on the front lines, replaced later by newer designs.

A soldier poses with a Hythe Mk III Gun Camera during training activities at Ellington Field, Houston, Texas in April of 1918. The Mk III, built to match the size, handling, and weight of a Lewis Gun, was used to train aerial gunners, recording a photograph when the trigger was pulled, for later review, when an instructor could coach trainees on better aiming strategies.

Captain Ross-Smith (left) and Observer in front of a Modern Bristol Fighter, 1st Squadron A.F.C. Palestine, February 1918. This image was taken using the Paget process, an early experiment in color photography.

Lieutenant Kirk Booth of the U.S. Signal Corps being lifted skyward by the giant Perkins man-carrying kite at Camp Devens, Ayer, Massachusetts. While the United States never used these kites during the war, the German and French armies put some to use on the front lines.

Wreckage of a German Albatross D. III fighter biplane.

Unidentified pilot wearing a type of breathing apparatus. Image taken by O.I.C Photographic Detachment, Hazelhurst Field, Long Island, New York.

A Farman airplane with rockets attached to its struts.

A German balloon being shot down.

An aircraft in flames falls from the sky.

A German Pfalz Dr.I single-seat triplane fighter aircraft, ca. 1918.

Observation Balloons near Coblenz, Germany.

Observer in a German balloon gondola shoots off light signals with a pistol.

Night Flight at Le Bourget, France.

British reconnaissance plane flying over enemy lines, in France.

Bombing Montmedy, 42 km north of Verdun, while American troops advance in the Meuse-Argonne sector. Three bombs have been released by a U.S. bomber, one striking a supply station, the other two in mid-air, visible on their way down. Black puffs of smoke indicate anti-aircraft fire. To the right (west), a building with a Red Cross symbol can be seen.

German soldiers attend to an upended German aircraft.

Japanese aviator, 1914.

A Sunday morning service in an aerodrome in France. The Chaplain conducting the service from an aeroplane.

An observer in the tail tip of the English airship R33 on March 6, 1919 in Selby, England.

Soldiers carry a set of German airplane wings.

Captain Maurice Happe, rear seat, commander of French squadron MF 29, seated in his Farman MF.11 Shorthorn bomber with a Captain Berthaut. The plane bears the insignia of the first unit, a Croix de Guerre, ca. 1915.

A German airplane over the Pyramids of Giza in Egypt.

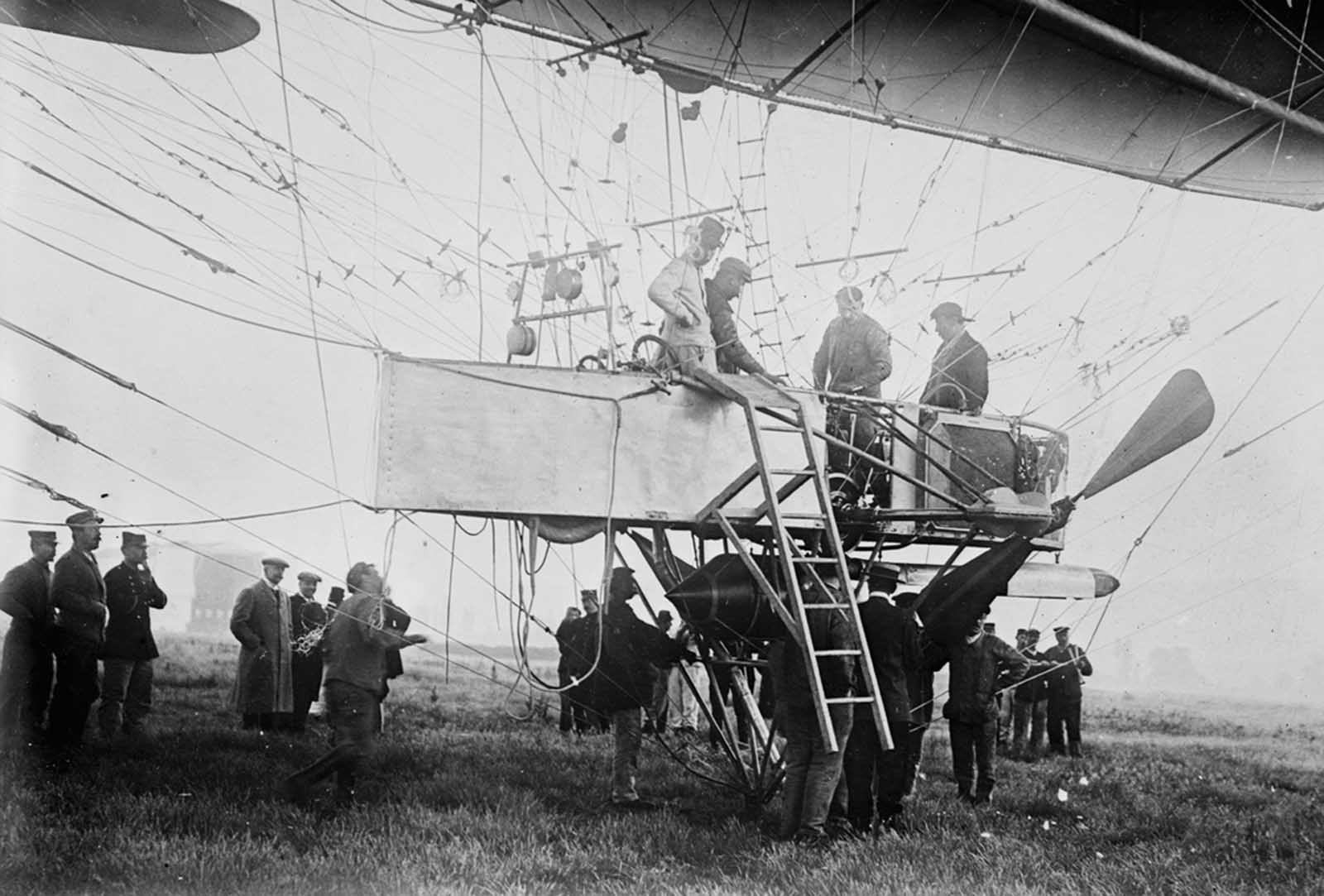

Car of French Military Dirigible “Republique”.

A German pilot lies dead in his crashed airplane in France, in 1918.

A German Pfalz E.I prepares to land, April 1916.

A returning observation balloon. A small army of men, dwarfed by the balloon, are controlling its descent with a multitude of ropes. The basket attached to the balloon, with space for two people, can be seen sitting on the ground. Frequently a target for gunfire, those conducting observations in these balloons were required to wear parachutes for a swift descent if necessary.

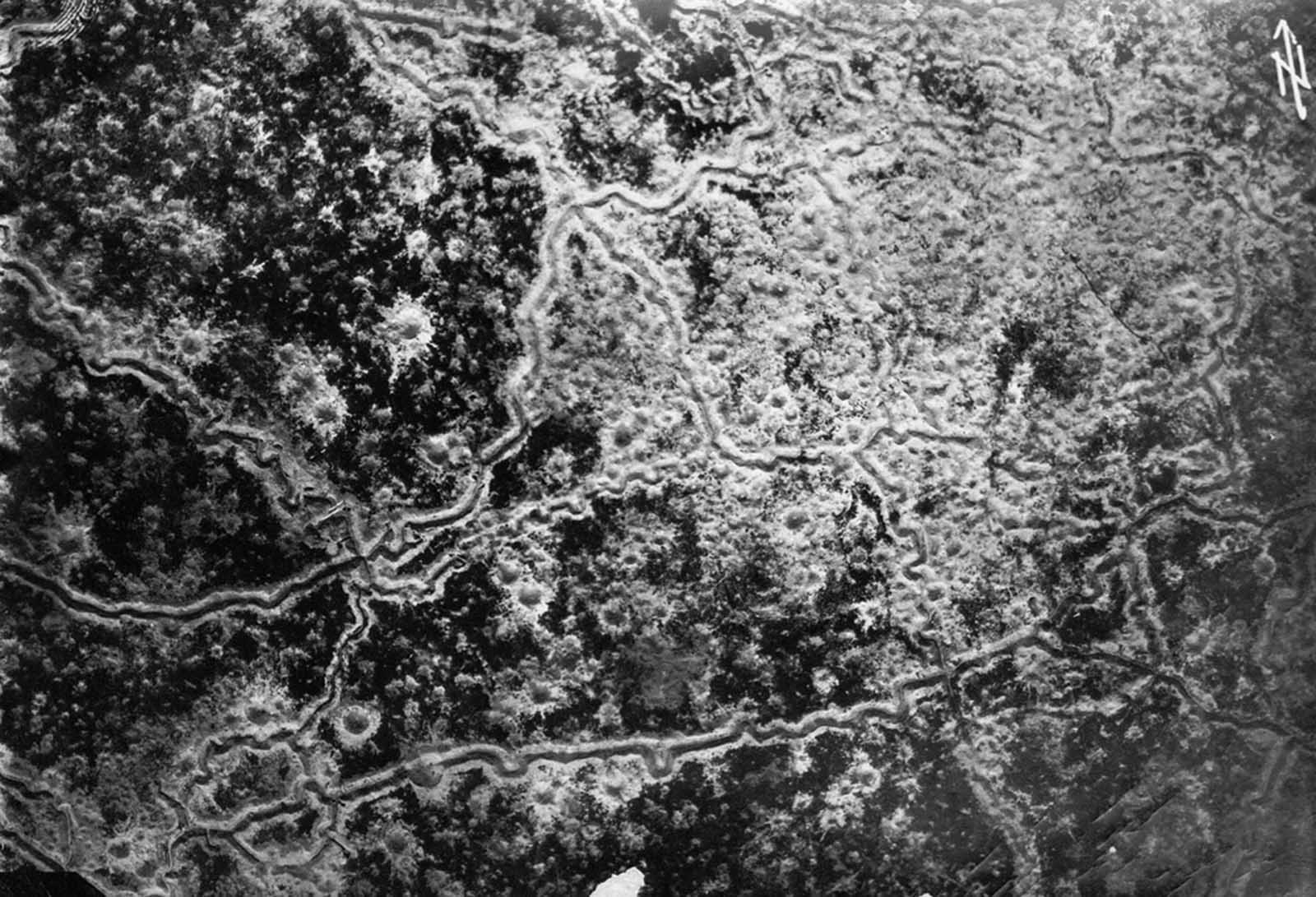

Aerial reconnaissance photograph showing a landscape scarred by trench lines and artillery craters. Photograph by pilot Richard Scholl and his co-pilot Lieutenant Anderer near Guignicourt, northern France, August 8, 1918. One month later, Richard Scholl was reported missing.

German hydroplane, ca. 1918.

French Cavalry observe an Army airplane fly past.

Attaching a 100 kg bomb to a German airplane.

Soldiers silhouetted against the sky prepare to fire an anti-aircraft gun. On the right of the photograph a soldier is being handed a large shell for the gun. The Battle of Broodseinde (October 1917) was part of a larger offensive – the third Battle of Ypres – engineered by Sir Douglas Haig to capture the Passchendaele ridge.

An aircraft. crashed and burning in German territory, ca. 1917.

A Sopwith 1 1/2 Strutter biplane aircraft taking off from a platform built on top of HMAS Australia’s midships “Q” turret, in 1918.

An aerial photographer with a Graflex camera, ca. 1917-18.

14th Photo Section, 1st Army, “The Balloonatic Section”. Capt. A. W. Stevens (center, front row) and personnel. Ca. 1918. Air Service Photographic Section.

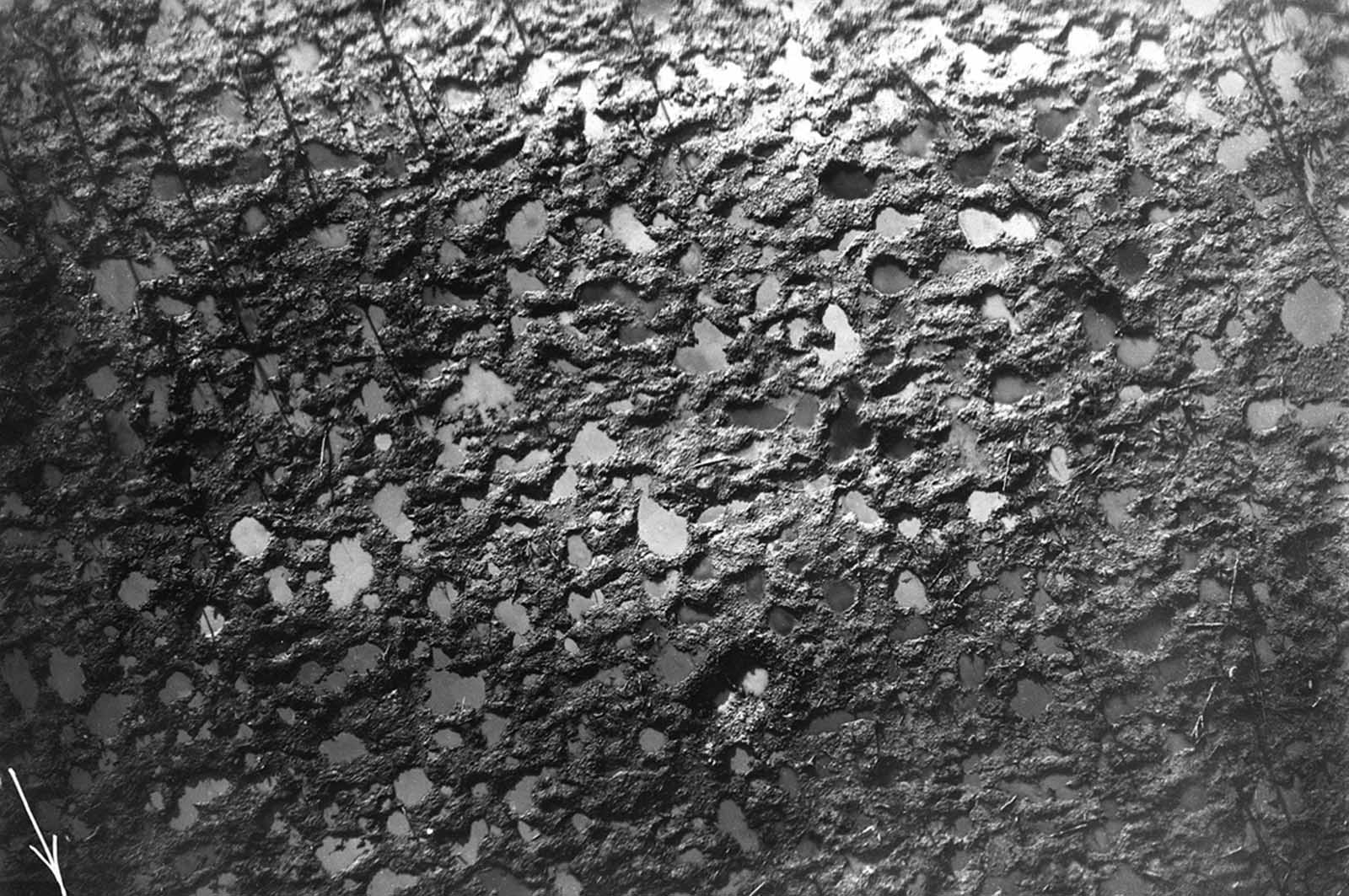

Aerial photo of a cratered battlefield. The dark diagonal lines are the shadows of the few remaining tree trunks.

A British Commander starting off on a raid, flying an Airco DH.2 biplane.

The bombarded barracks at Ypres, viewed from 500 ft.

No. 1 Squadron, a unit of the Australian Flying Corps, in Palestine in 1918.

Returning from a reconnaissance flight during World War I, a view of the clouds from above.

Air force units were reorganized on numerous occasions to meet the growing need of this new weapon. Crucially, aerial strategies developed during the First World War laid the foundations for a modern form of warfare in the sky. During the course of the War, German Aircraft Losses accounted to 27,637 by all causes, while the Entente Losses numbered over 88,613 lost (52,640 France & 35,973 Great Britain).