Some researchers believe the ancestors of modern humans migrated from their homelands in Africa to Europe and Asia 60,000 years ago in response to the climate becoming dryer. If food and water were becoming increasingly scarce, the established African migration theory states, early humans may have left Africa in search of wetter and more fertile lands. This seems like a logical conclusion. But new research published in the journal Communications, Earth & Environment by geographer Frank Schäbitz from the University of Cologne and several colleagues has called this idea into question.

It appears Homo sapiens (modern man) first began leaving Africa in large numbers when the climate was humid and ample supplies of food and water were available. Their African migrations were driven not by desperation, but more likely by curiosity about what might lie over the next hill or beyond the next valley.

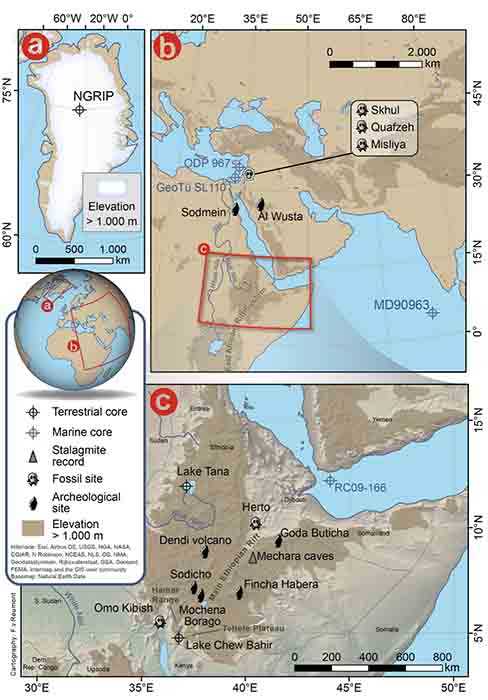

Location maps from the African migration study showing the area of research in Ethiopia where the core samples were taken. (Communications, Earth & Environment)

African Migrations and The Influence of Local Climate Change

Professor Schäbitz recruited a team of international scientists to perform a thorough reconstruction of the climate of Ethiopia over the past 200,000 years.

To achieve this goal, they extracted a 1,000-foot (300-meter) core sample from the ancient Lake Chew Bahir basin in southern Ethiopia. After examining the layers of the sample closely, they confirmed that the climate in East Africa was quite warm and wet between 200,000 and 125,000 years ago. It started becoming progressively more arid after that, with the drying picking up speed around 60,000 years ago.

This data fit well with previous discoveries. But using the most sophisticated techniques for analysis available, the scientists were able to identify many smaller cycles of climate change that occurred within the larger time frames. The climate tended to get wetter or dryer than normal at various times, for periods of a few thousand or a few hundred years. In some instances, the fluctuations were even shorter.

“Some of our proxies allow time resolution for specific decades in large sections of the core, which has not been done before for this part of Africa,” Schäbitz explained in a University of Cologne press release announcing his team’s discoveries. “That way we can capture very short-term climate changes representing less than a human lifetime.”

In contradiction to the long-term trend, Schäbitz and his colleagues discovered that the climate in East Africa had become wetter, warmer, and more hospitable again around 70,000 years ago. In fact, this was the last significant wet period the region experienced, according to the core analysis.

Conditions took an abrupt turn for the worse 60,000 years ago, and Schäbitz believes that it was sometime during that 10,000-year window that early Homo sapiens began their African migrations northward and eastward in large numbers.

African migrations were influenced by short climate change cycles, often less than a human lifetime, that forced people to move “up” or “down” depending on where there was more food and water. (Jo Raphael / Adobe Stock)

“We hypothesize that the evidence of dry-humid climate fluctuations in East Africa found in our drill core had a significant impact on the evolution and mobility of our ancestors,” said Schäbitz. “Migration out of Africa was possible several times during the last 200,000 years, during periods when the climate was wetter, and has led to the spread of our ancestors as far as Europe.”

The idea is that people would have needed access to plenty of food and water all along the way to complete long-distance trips on foot. Since they might be traveling for months or years, carrying enough supplies with them would have been impossible.

As for the theory that humans might have had no choice but to leave when excessively dry conditions developed in East Africa, Schäbitz points to evidence that shows they did something else.

“It is interesting that just in the period from 60,000 to 14,000 years ago, when the lowlands of East Africa were repeatedly particularly dry, numerous archaeological findings in the high altitudes of the Ethiopian mountains bear witness to the presence of our ancestors there,” he noted. “We suspect that the greater ‘environmental stress’ at lower elevations forced this development.”

Rather than flee when times became difficult and resources scarce, early humans living in East Africa simply migrated upward, into the cooler and damper highlands.

A green patch or part of a longer green corridor in the Sahara desert in Morocco, which long ago may have been utilized by homo sapiens on their African migrations heading north. (Michal / Adobe Stock)

Green Corridors through the Sahara?

Africa is a large continent, meaning African migrations from sub-Saharan Africa could have followed many different routes.

It is known that some traveled northward along the Nile River Valley on their way to the Middle East, and then eventually on to Europe and Asia. Others took a much shorter sea route, crossing the narrow Bab-el-Mandeb strait that separates East Africa from modern-day Yemen and the Arabian Peninsula. Still others may have tried to cross the Sahara Desert, going north and west.

Those who chose the latter route might have seem destined for failure. But in 2008, a team of researchers from the United Kingdom published an article in the journal PNAS that suggested crossing the Sahara would have been possible at one time. Not necessarily 70,000 years ago, but during an earlier period, when much smaller numbers of early Homo sapiens were beginning to venture out into the broader world.

Interestingly, the work of these scientists mirrored that of Frank Schäbitz and his research team. They operated under the same assumptions and reached the same type of conclusion.

The scientists were trying to explain how a few 120,000-year-old fossilized human remains could have been found in the Middle East, when there was no evidence to show that any humans had been traveling northward along the Nile River Valley that long ago. They eventually determined that in those early African migration migrants must have traveled across the Sahara, during a time when fluctuations in the climate would have made parts of the Sahara wetter than usual.

In support of their hypothesis, they pointed to space-based radar images that revealed the existence of ancient, buried riverbeds that once crossed the Sahara on their way to the Mediterranean. Since climate reconstructions of the past have shown that Africa experienced wetter-than-usual conditions between approximately 130,000 and 117,000 years ago, they believe those rivers might have existed at that time.

If so, they would have created green river valley corridors that migrants could have followed from East and South Africa all the way to the Mediterranean. Along these green corridors, food and water would have been plentiful, making long-distance travel possible.

Evening view of an African landscape showing that some areas are green while others are dry or barren. This was true during the African migrations, and also today. (milosk50 / Adobe Stock)

The Past and Future History of an Endlessly Shifting Climate

It should be noted that the climate changes experienced hundreds of thousands of years ago were caused by changes in the orbit and rotation of the Earth. Over long periods of time, slight variations in both alters the distance between the Earth and the Sun. This either increases or reduces the sunlight reaching the planet’s surface, causing both long-term and short-term fluctuations in the climate.

The research linking changes in the Earth’s movement patterns to climate shifts in ancient East Africa is solid. It tells us what happened in the past and why. But it also functions as a preview of our planet’s future.

While much of the current focus in climate science is on man-made climate change, even if that problem is eventually addressed it will not stop climate cycles from occurring. Among other effects, continuing alterations in the Earth’s orbit will bring on another Ice Age at some point.

A long, cold, seemingly endless winter will eventually return, forcing new rounds of mass human migration that will change human history forever—just as the migration out of Africa changed it so many millennia ago.