A team of South African and American archaeologists exploring the Rising Star cave system in central South Africa discovered something that seems quite anomalous. In the deepest, darkest recesses of an almost inaccessible part of one cave, they found the skeletal remains of a small child who likely lived between 250,000 and 300,000 years ago, during the Middle Pleistocene epoch. The child belonged to the mysterious archaic human species Homo naledi, which is known about exclusively from explorations of the Rising Star cave system.

An illustration by Boniswa Khumalo of the skull of the Homo naledi child known as Leti. (Boniswa Khumalo / University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg)

The Homo naledi Child Leti Found At Deepest Cave Level

Over the past eight years, explorers in the Rising Star system have recovered nearly 2,000 samples of Homo naledi teeth and bones. But the skeleton of the small child was found at a greater depth than any of the other samples, and that is what makes this discovery so extraordinary.

The discoverers have named the child “Leti,” which means “lost one” in the indigenous South African Setswana language.

The unfortunate youngster’s remains were found stuffed inside a narrow crevice on a cave wall, deep in the cave’s interior. The scientists recovered six teeth and 28 skull fragments in all from her eternal resting place. Based on the size of the teeth and skull, they estimate Leti was between the ages of four and six years old when she died.

The route to the ledge where the child’s remains were found was extremely hard to reach. It featured several tight squeezes through claustrophobia-inducing narrow passageways, plus steep vertical drops that must be navigated with great care. The route ends at a narrow crevice located 150 meters (492 feet) underground, far away from any natural light.

“No one involved in this had any expectations that we were going to find naledi bones in these situations,” John Hawks, a University of Wisconsin-Madison paleoanthropologist, said to National Geographic. “We’re pushing into places that are meters and meters down impossible passages.”

The skulls of 4 known archaic hominins with Homo naledi on the far right. (Chris Stringer / CC BY 4.0)

Who Were the Homo naledi?

Any discovery that sheds light on Homo naledi practices is welcomed by scientists, who must depend entirely on the Rising Star cave system for information about this long-extinct human cousin.

“Homo naledi remains one of the most enigmatic ancient human relatives ever discovered,” Rising Star Expedition leader Lee Berger, a paleoanthropologist from South Africa’s University of the Witwatersrand, explained in a press release about the latest find.

“It is clearly a primitive species, existing at a time when previously we thought only modern humans were in Africa. Its very presence at that time and in this place complexifies our understanding of who did what first concerning the invention of complex stone tool cultures and even ritual practices.”

Physically, this species was built similarly to Australopithecus, an ancient possible forerunner to Homo sapiens (modern humans) that lived in Africa three million years ago. In addition to the sturdy build and small archaic brains they shared with this species, they also possessed many characteristics similar to those of modern humans, which reveals interesting details about how human evolution unfolded over time.

Dating at Rising Star suggests Homo naledi went extinct at least 236,000 years ago. As of now, the full range of their territory is unknown (although they surely must have lived at locations far from the Rising Star caves).

The LES1 Homo naledi cranium found at a higher level than Leti’s remains in the Rising Star caves. (John Hawks, et al / CC BY 4.0)

The Unmistakable Signs of an Intentional Burial

As the South African and American scientists explain in a new article appearing in the journal Paleoanthropology, the child’s skeletal remains were found during a 2017-2018 Rising Star caves archaeological mapping project. The scientists charted more than 1,000 feet (305 meters) of new passageways during this initiative, many of which followed routes deep into the earth.

The mapping project took them well into the interior Dinaldi cave subsystem, which is where almost all of the Homo naledi remains have been recovered over the years. Notably, this part of the cave is only reachable via a steep and risky descent down a 40-foot (12-meter) chute, or by crawling along a twisting and exceptionally narrow path that winds downward through the rock.

The spacious entryway to the subsystem is known as the Dinaldi Chamber, and the small Homo naledi child’s skeleton was discovered about 39 feet (12 meters) away from this central gathering spot. Hers is one of five skeletons explorers have found outside the main chamber, where remains linked to 15 Homo naledi skeletons have been identified.

There have been ancient skeletons discovered deep inside caves that were not placed there by humans. Caves are prone to flooding, and water rushing in from outside has been known to deposit human and animal skeletal remains inside caves from time to time. Large predators who feed occasionally on humans may drag their kills into caves before consuming them as well.

In this instance, there is no evidence to suggest either of these things happened to any of the archaic human remains found in the Rising Star system. No signs of flooding in and around the Dinaldi Chamber have been observed. There are also no signs of gnawing or biting on any of the bones, which would be a telltale sign of predator activity.

If these possibilities can be eliminated, the only other alternative is that the bones were put inside the cave intentionally by living members of a Homo naledi group. By definition, this would be a type of funerary practice, where the dead are carefully and deliberately interred to protect or preserve their bodies from scavengers and the elements, and perhaps also to prepare them for entrance into the afterworld.

“We can see no other reason for this small child’s skull being in an extraordinarily difficult to reach and dangerous positioning,” said Berger.

The crevice where Leti was placed would have been chosen because of its ideal shape and size. Its bottom formed a flat ledge about six inches (15 centimeters) across and 31 inches (80 centimeters deep). It was much too small for an adult but would have been a perfectly appropriate resting spot for a small child. Its location was difficult to get to, but from the Homo naledi perspective that might have made it seem like a safe and secure resting place.

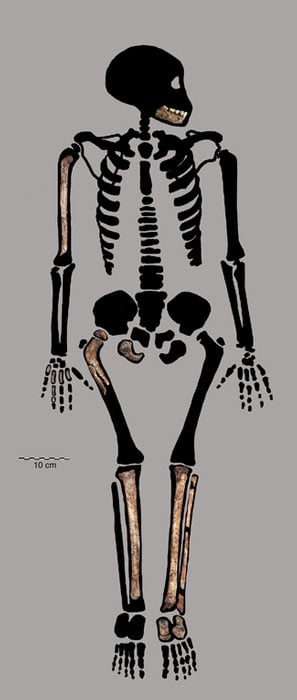

Skeletal reconstruction with known remains of a juvenile Homo naledi specimen known as DH7. (Debra R. Bolter, et al / CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Funerary Practices of Ancient Man

If Homo naledi did have funerary customs, or rules about how the dead should be treated, it would mean they possessed a level of cultural sophistication that was once considered impossible for archaic human species.

Other discoveries have shown that customs related to the proper disposal of the dead go far back into history.

It is now widely accepted that Neanderthals had distinctive funerary practices, as revealed by discoveries of multiple Neanderthal skeletons deliberately buried in southwestern France at the La Ferrassie archaeological site.

Earlier this year, archaeologists announced they’d discovered the 78,000-year-old remains of a three-year-old child that had been intentionally and carefully buried near the mouth of Panga ya Saidi cave in Kenya.

Some archaeologists have even argued that a depository of 430,000-year-old human bones found in Spain’s Sima de los Huesos cave are most likely the result of intentional burial (although this thesis is considered controversial).

There is no way to know what the funerary rituals of an archaic human species meant to the people who practiced them. Their motivations could have been deeply spiritual, or they may simply have wanted to protect the remains of the deceased from animal scavengers. But regardless of their purpose, the existence of such practices shows that archaic humans were complex beings, and perhaps not so different from modern humans as some might have imagined.