‘Biblical Apocrypha’ sounds like something out of a conspiracy theorist’s darkest dreams. Books that have been hidden away from us. Books that contain secret information on the origins of Christianity. As is so often the case, this isn’t exactly true. The history of the Apocrypha isn’t quite as shadowy as some writers would have us believe. However, the Apocrypha do offer us a fascinating glimpse into the early origins of Christianity, and the power wielded by a handful of theologians that died centuries ago.

What are the Biblical Apocrypha?

Put simply, the biblical Apocrypha are texts that have been left out of the Biblical canon. Some Christian sects leave them out completely, while others may include them in their Bibles, but make it clear they are non-canonical.

The biblical canon is the set of texts which a specific Jewish or Christian community regards as part of the Bible. There are many different Christian and Jewish sects, with different biblical canons. For example, one of the big differences between Catholicism and Protestantism is their biblical canons. While Catholics tend to include the Apocrypha in their Old Testament, canonizing them, modern Protestant Bibles tend to eliminate the Apocrypha altogether.

Protocanonical Vs. Deuterocanonical

A prime example of differences in the biblical canon is the protocanonical and deuterocanonical texts. The protocanonical books are the books of the Old Testament which are also included in the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh). These are the books that the very early Christians (who were the precursors to Orthodox Christians) believed to be canon.

On the other hand, the deuterocanonical texts are the “second canon”. They are considered canon by the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodox Church, and a handful of others as canonical representations of the Old Testament. However, Protestants disagree, regarding these texts as Apocrypha.

Martin Luther posting his 95 theses in 1517 is considered a starting point of the Protestant Reformation. Painting by Ferdinand Pauwels, 1872 (Public Domain)

Different Bible; Different Apocrypha

This just scratches the surface of differences in biblical canon. Throughout history, as different versions of the Bible have been published, the issue has only gotten more confusing. Each Bible handles the issue of the Apocrypha differently.

The Gutenberg Bible of 1455 doesn’t have a section for Apocrypha. Instead, its Old Testament simply included the texts that many thought to be apocryphal. Pope Clement VIII would later move these to the index with the 1592 edition of the Clementine Vulgate.

In comparison, when Martin Luther released his German translation, the Lutheran Bible, in 1534, he included a whole section dedicated to Apocrypha. Furthermore, he had his doubts about the veracity of four of the New Testaments books, and so he moved them to the back of the Bible. The King James Bible of 1611 followed in Luther’s footsteps, adding an Apocrypha section. Today, when we talk about Apocrypha, in general we are normally referring to the books listed within the King James Version’s Apocrypha section.

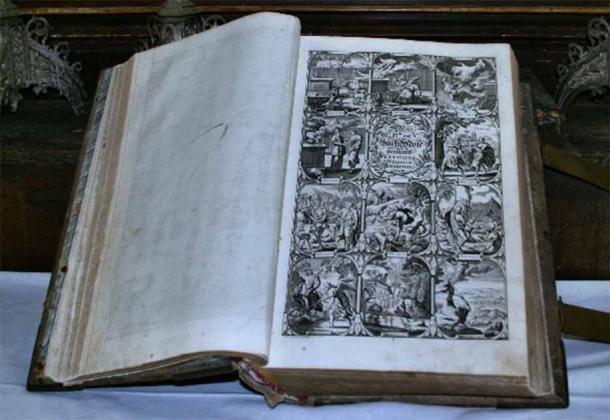

A Luther Bible, from 1534 (Public Domain)

The Gutenberg, Lutheran, and King James Bibles are the most well-known versions of ‘the Bible’, but of course, there are many, many more. Some include all books of the Apocrypha, others only include some, and each orders it in a different way. More commonly, most modern editions of the Bible leave it out altogether, but we’ll discuss that later.

Lutheran Bibles had the Apocrypha sectioned off at the end (Koosg / CC BY SA 3.0)

Apocrypha vs Pseudepigrapha

To add to the confusion about what counts as biblical canon, we also have pseudepigrapha to contend with. As mentioned, Apocrypha are the books outside of the canon. These were usually books that were not included when the New Testament became official, after Constantine I of Rome converted to Christianity.

Pseudepigrapha translates as “false writing”. For the most part, these were forgeries written in a biblical style. They were often written in the name of famous people from the past, to lend them credibility.

Sometimes the pseudepigrapha sought to answer questions early Christians may have had about the Bible. For example, what was Jesus like as a child? Others simply sought to entertain early Christians using characters they were already familiar with. This led to weird combinations, like romantic biblical stories.

Canon or Apocrypha: Who Decided?

Today, deciding which stories are Apocrypha should be relatively simple. Does it appear in the Apocrypha section of the Bible, especially in the King James Bible? Then it’s Apocrypha. Anything else is more than likely pseudepigrapha.

But who decided what was canon and what wasn’t? When asking these questions as historians, we have to be careful not to offend. When examining the Bible as a historic text, the simple fact is, much of what its writers claimed took place can’t be verified.

The Bible may mention some people from throughout history, but it has a habit of embellishing the truth. Take King Herod, for example: we know he was 100% real, and it is likely he had three of his sons executed. However, besides the Bible, there is no other evidence stating that he had everyone’s infant sons executed.

So, who decided what went in the Bible? How did they decide “this miraculous story happened, but this other one didn’t”? This is where early Christian theologians played an important role.

These theologians were largely responsible for shaping early Christianity. It should be no surprise that they tailored the religion to fit their own beliefs. If an early Bible story had a strong pagan influence, for example, it became heretical and therefore pseudepigrapha. Was it more focused on entertaining, rather than teaching an important lesson? Then again, it was generally labelled heretical, and / or pseudepigrapha.

The men who wrote the Bible were human beings with their own biases, motivations, and agendas. For example, how did Martin Luther choose which texts went into the Apocrypha? How could he be sure which biblical stories were ‘true’ and which weren’t? He used his faith. Luther was unhappy with many of the teachings of the Catholic Church, so he created his form of Christianity, Lutheranism, which largely led to the Protestant Reformation.

When Luther created his Apocrypha, he took the parts of the Catholic Old Testament which didn’t fully support his new religion and put them in the Apocrypha. He interpreted the Bible in a way that supported his beliefs, and then made sure his Lutheran Bible reflected those beliefs.

The King James Bible did something similar. While it is broadly similar to the Lutheran Bible, its Apocrypha does vary slightly. Why? Because King James, a leader with his own goals, ordered that the Bible be translated in such a way that it reflected the teachings of the Church of England. A church that, as monarch, he was the head of.

The Infancy Gospel of Thomas: A Different Jesus

Perhaps the best example of why a Bible story might find itself labeled as pseudepigrapha is the Infancy Gospel of Thomas. Early Christians wanted to know more about the early life of Jesus. The canon stories jump straight from the birth of Jesus to his life as a young man.

The Infancy reads very much like a superhero or supervillain origin story. In it, Jesus reads like a spoiled, psychotic brat. He misuses his powers for personal gain, tortures his tutor, and even kills another boy who he doesn’t like. By the end of the story, Jesus has learned to control his powers and resembles the canon Jesus to an extent, but it’s a rough road there.

The Jesus of the Infancy Gospel of Thomas resembles the gods of the old pagan myths. Spoiled, rash, and with little regard for the lives of mortals. It is easy to see why early theologians would look at this depiction of their martyr and deem it heretical. It did not fit with the religious narrative they were trying to sell.

One of the “Tring Tiles”, circa 1330, depicting the antics of a teenage Jesus (Johnbod / CC BY SA 3.0)

Why Did the Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha Disappear?

The conspiracy theorists out there like to point at the Apocrypha and pseudepigrapha as proof of grand sweeping conspiracies. They like to question why it is that so many people hailing from predominantly Christian countries have never heard of many of these biblical tales. Surely this is proof of the Illuminati, or the Knights Templar, or someone else controlling what we believe. What don’t they want us to know?!?

As is so often the case, the reality isn’t quite as exciting. It is interesting though! The first ‘disappearance’ of the Apocrypha occurred in revolutionary Britain during the 1600s. The Puritans were dogmatic, following the Sola Scriptura standard (Scripture Alone). This means they only cared about and were interested in the biblical canon. Everything in the Apocrypha was worse than useless to them; it was borderline offensive. The Westminster Confession of Faith excluded the Apocrypha from the canon, and so most British publishers stopped printing it during this period.

Eventually, the Apocrypha was banned by those offended by it. This time, it really stuck, and was likely the reason so many people today are unfamiliar with the Apocrypha and tend to sensationalize it.

In 1826, the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS) announced that they would no longer fund any printing of the Apocrypha, anywhere. The National Bible Society of Scotland had petitioned them on the matter, and the BFBS agreed. This ban lasted until 1964 in the United States and 1966 in the UK. The result is most modern Bibles, including reprints of the King James and non-Catholic reprints of the Clementine Vulgate, omit the Apocrypha. Even reprints of even older, more obscure Bibles skip the Apocrypha.

The reason the Apocrypha was seemingly hidden from millions of Christians? Simple economics. The more pages you print, the more expensive the book is to produce and transport. By this point, most Christians (except Catholics) were of the mind that the Apocrypha was non-canonical. So why waste money printing it?

The more cheap, readily available Bibles that Christians distributed, the more minds the Bible was able to reach. Hopefully, meaning more Christians. It was a simple cost-benefit analysis.

There it is: no big secret. The only reason the apocalyptic apocrypha seemed to disappear for such a long period is that printing it wasn’t deemed financially prudent. However, the pseudepigrapha is a slightly different story.

An argument can be made that efforts were made to hide pseudepigrapha from early Christians. Most pseudepigraphical stories were deemed heretical by early religious leaders. These men were trying to shape a young religion, and so they simply banned whatever contradicted their teachings.

Many pseudepigrapha disappeared and were largely lost to history. This is not uncommon; anyone familiar with ancient history is used to lost sources. Unfortunately, this has led to huge gaps in our understanding of Greek, Roman, and Egyptian religion, because so many sources didn’t survive.

In more modern times, archaeologists and historians have begun re-discovering pseudepigrapha that had been thought lost to time. These often give us a fascinating insight into the very early days of both Christianity and Judaism. No one is hiding them; a quick Google search will bring up lots of examples.

Taking out parts of the Bible to save money? Simple economics. (Lightfield Studios / Adobe Stock)

Apocalyptic Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha

In recent years, society has become a little obsessed with the apocalypse. Anything apocalypse-related sells big. Many are also a little fixated on conspiracy theories. Unsurprisingly, this means that in recent years, the idea of the Apocrypha being ‘hidden’ has gone hand in hand with conspiracy theories regarding the apocalypse. So, how apocalyptic is the Apocrypha?

In truth, only one of the texts usually attributed as Apocrypha even deals with an apocalypse: 2 Esdras. In it, Ezra, a scribe, has four visions relating to the apocalypse. There is nothing particularly inflammatory in it.

The Book of Esdras describes a three-headed eagle (Public Domain)

The Pseudepigrapha, however, deal more with the apocalypses. The Apocalypse of Abraham, the Apocalypse of Moses, the Apocalypse of Paul, and the Apocalypse of Peter all offer more sensationalized versions of the apocalypse than what is included in the Bible. The Apocalypse of Peter in particular has survived in many ancient manuscripts. It gives us a slightly more detailed depiction of what life is like in heaven.

There is nothing in any of these texts which would make one think there is a reason they were hidden away. Instead, the texts simply don’t fit the canon laid out by earlier biblical scholars. Anyone hoping for DaVinci Code-level revelations when reading them is bound to be sorely disappointed.

Most depictions of Armageddon and the Apocalypse are actually kept in the Bible (IgorZH / Adobe Stock)

Conclusion

Studying the Apocrypha can be unsatisfying for anyone expecting a grand revelation that would turn the established church on its head. It is simply just a collection of ‘extra’ stories that didn’t make it into the canon and then were largely cut altogether because of financial constraints.

In fact, most of the Apocrypha appear in the Old Testament of Catholic Bibles, so they’re really not very well hidden at all. The pseudepigrapha are perhaps more interesting. They offer raunchy, sensationalized versions of characters already established in the Bible. A psycho Jesus who kills little boys and tortures people? That story will sell. And it is easy to see why people might wonder what else was hidden from them.

However, in fact, the pseudepigrapha are little more than fan-fiction: stories written to entertain people whose lives largely revolved around their religion, while filling in gaps in the established canon.

This does not mean the study of these texts is dull or unimportant, however. Studying both the Apocrypha and pseudepigrapha shows us the effect certain people have had on the development of modern Christianity and its religious text. It reminds us that the Bible is a very old text which has been translated myriad times, and that, like any text, it is very open to interpretation.