Caught for breaking and entering as well as attacking animals with a machete when he was just a teenager, Ivan Milat eventually graduated to homicide and became known as the “Backpacker Murderer” after slaying seven hikers starting in 1989.

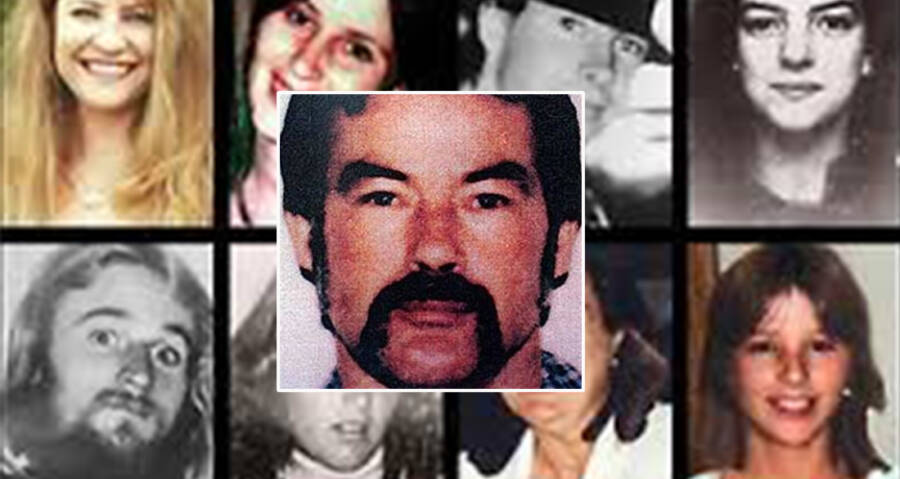

In the early 1990s, Australia was rocked by the gruesome murders of seven backpackers in Belanglo State Forest. To this day, the “Backpacker Murders” remain some of the worst killings in the country’s history — and it was all the work of one disturbing predator named Ivan Milat.

“There are just some people who are dirty, rotten people,” said journalist Mark Whittaker who authored Sins of the Brother, a book about the Backpacker Murders which were later fodder for the cult classic horror film Wolf Creek.

“If you speak to five psychiatrists, you get five separate opinions. All I know is that I was often sitting there at the typewriter, crying… I just don’t think there’s a moral to the story.”

Ivan Milat’s Early Crimes Before Graduating To Murder

News Corp AustraliaThe Milat brood grew up in a violent household.

Like many serial killers, Ivan Milat grew up in a dysfunctional family.

He was born Ivan Robert Marko Milat on December 27, 1944, to a poor family of Croatian immigrants in Guildford, Australia. His father was often violent and his mother often pregnant. She had 14 children, including Milat who was the fifth. Two of his other 13 siblings died.

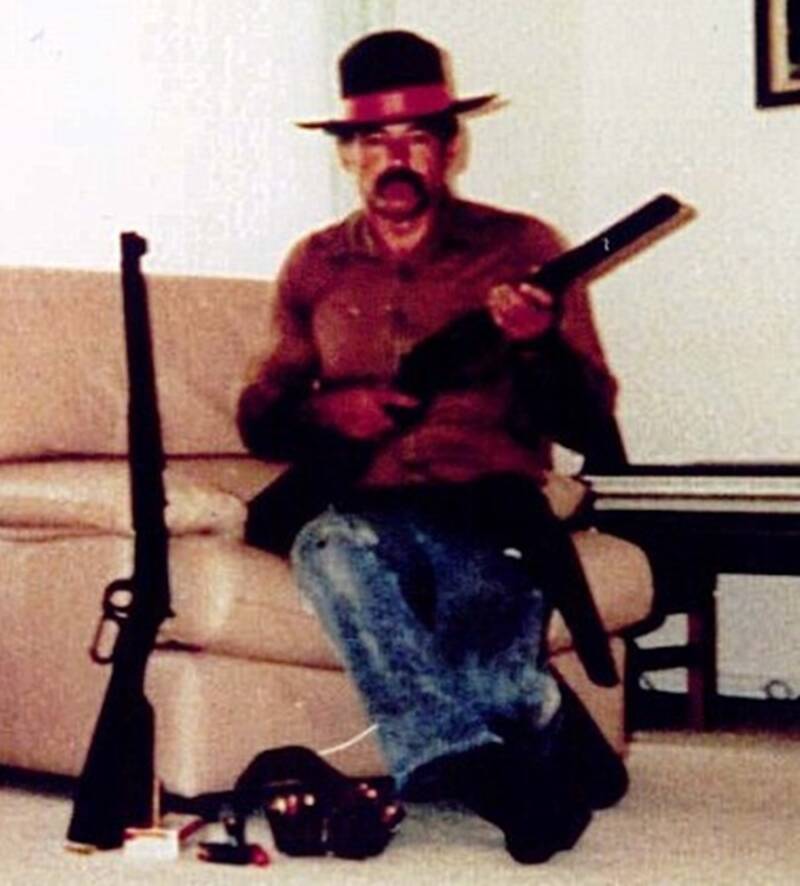

Milat and his overcrowded family grew up in a shack house in Moorebank, a suburb located at the outskirts of Sydney, Australia. The Milat siblings were enrolled in private Catholic schools, but after classes would get into mischief. They were used to handling knives and firearms and spent their afternoons shooting at targets in their parents’ yard. Milat was a well-known delinquent to the authorities by the age of 13.

Soon enough, his crimes escalated. By 17, he’d been sent to a juvenile detention center for theft. By 19, he broke into a local store.

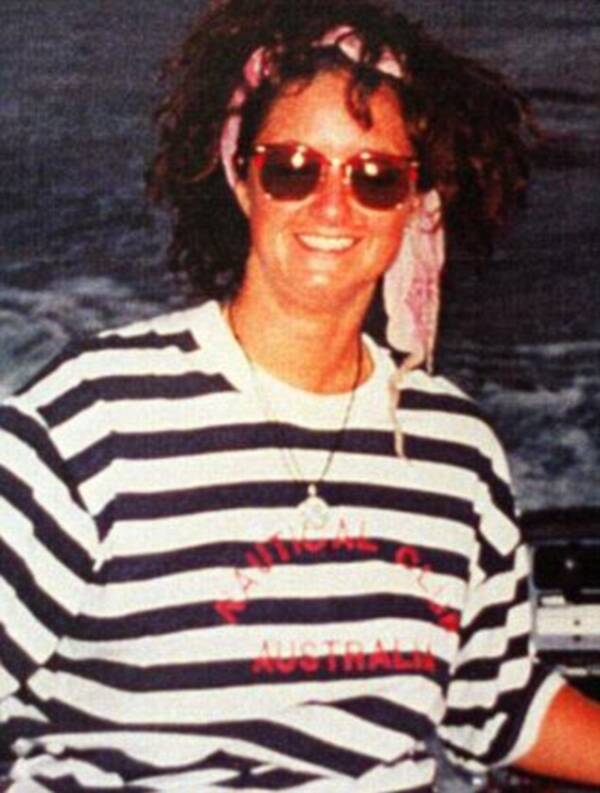

Daily MailBefore he became Australia’s number one killer, Ivan Milat had a violent criminal history.

According to Milat’s older brother, Boris, who is also the only member of the Milat family who has spoken publicly against him, Ivan Milat showed signs of psychopathic behavior from an early age.

When Ivan Milat was 17 he allegedly confessed to Boris about accidentally shooting a taxi driver during a stick-up gone awry. The man was left paralyzed from the waist down. Milat was never caught and an innocent man was subsequently convicted and served five years in prison for his crime.

Then, in 1971 at age 26, Ivan Milat was charged with raping two female backpackers. But the sloppiness of the prosecutor’s evidence only served to get Milat acquitted. Perhaps having gotten away with this crime, Ivan Milat felt he could get away with more — and worse — crimes.

He attempted the rape and murder of two more women in 1977, for which he was never charged.

Daily MailIvan Milat had a love of firearms and knives since he was a kid. His violent crimes eventually became the true story of Wolf Creek, a cult classic horror film.

“[Ivan] was pretty normal up until 12, 14,” Boris said in an interview. “I heard about it from his mates, you know. They’d all boast about [how] they’d go out at night and do things with machetes. I heard he cut a dog in half with a machete while he was growing up.”

“He was going to kill somebody from the age of 10. It was built into him… I knew he was on a one-way trip. I knew that it was just a matter of how long.”

Ivan Milat married a woman 15 years his junior in 1984. But the marriage went south quickly and as a result, Milat burned down her parents home in Newcastle. His ex-wife testified against Milat in trial and said her ex-husband was obsessed with guns and known to be violent.

But Ivan Milat’s propensity for violence would only grow, fueling ever more gruesome crimes.

The Grisly Story Of The Backpacker Murders

Wikimedia CommonsAustralia’s Belanglo forest has become synonymous with the Backpacker Murders of the 1990s.

Even before the first of Ivan Milat’s victims had been found, a slew of backpackers were reported missing in the Belanglo Forest since 1989, including a teenaged couple en route to ConFest.

The first of Ivan Milat’s victims were found on September 19, 1992, in the Belanglo State Forest located in New South Wales. Two runners first stumbled on a concealed corpse, face down in the dirt, hands tied behind their back.

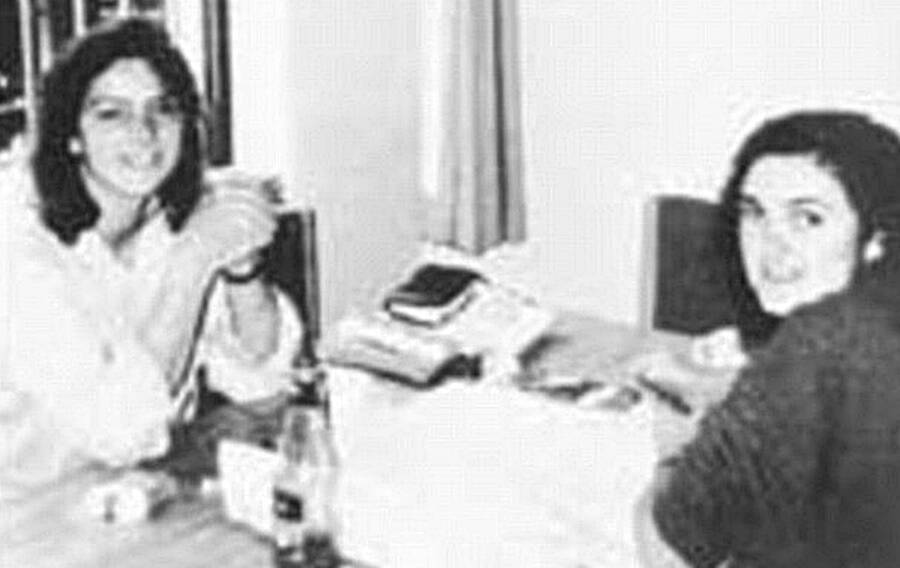

But then another body was found the following morning by police just 98 feet from the first body. Dental records identified the two bodies as British backpackers Caroline Clarke (21) and Joanne Walters (22), who were last seen months before in April on their way to Victoria to go fruit picking.

An autopsy report confirmed that the two had been brutally slaughtered. Clarke had been blindfolded and marched into the bush execution-style, then shot 10 times in the head. It was believed her body had been used for target practice.

Walters had been stabbed 14 times; four times in the chest, once in the neck, and nine times in the back which ultimately severed her spine.

APBackpackers Caroline Clarke and Joanne Walters were among the victims slaughtered in the Belanglo forest.

Suspecting they would find more bodies in the forest, investigators conducted a search of the area but came up empty-handed.

But they were right and eventually, more corpses would be unearthed in the coming year.

In October 1993, a local man searching for firewood discovered human bones in a remote part of the Belanglo State Forest. After returning with police, authorities quickly uncovered two bodies which were later identified as the young teenaged couple who had gone missing in 1989, Deborah Everist (19) and James Gibson (19).

Nineteen-year-old Gibson was found in the fetal position riddled with stab wounds so deep that his spine had been severed and lungs punctured. Everist had been beaten, her head fractured and jaw broken, and stabbed once in the back. The location of the teenagers’ bodies confounded police as their belongings had cropped up in December 1989, 75 miles north.

The next month, a skeleton was found in a clearing along a fire trail in the forest during a police sweep. The remains were later identified as missing German backpacker Simone Schmidl (21). She had also been stabbed so deeply that her spine had been severed.

On a nearby fire trail, two more corpses were discovered, including German travelers Gabor Neugebauer (21) and Anja Habschied (20) who had been missing since two years prior. Habschied had been decapitated, but investigators were never able to find her skull and Neugebauer had been shot in the head six times.

Daily MailVictim Simone Schmidl had been stabbed so forcefully that her spine had been severed in process.

The carnage was nothing like the local authorities had seen before. The killings dominated the news. The series of homicides earned the nickname “Backpacker Murders” considering the killer had targeted tourists hitchhiking their way through Australia.

“That shows you how malicious and nasty the murders were,” says retired New South Wales Police detective Clive Small, who led the investigation into the Backpacker Murders. “The deaths were being dragged out, and the fact that there were a number of deaths also shows that he was becoming more and more committed to the murders.”

The Search For The Backpacker Murderer

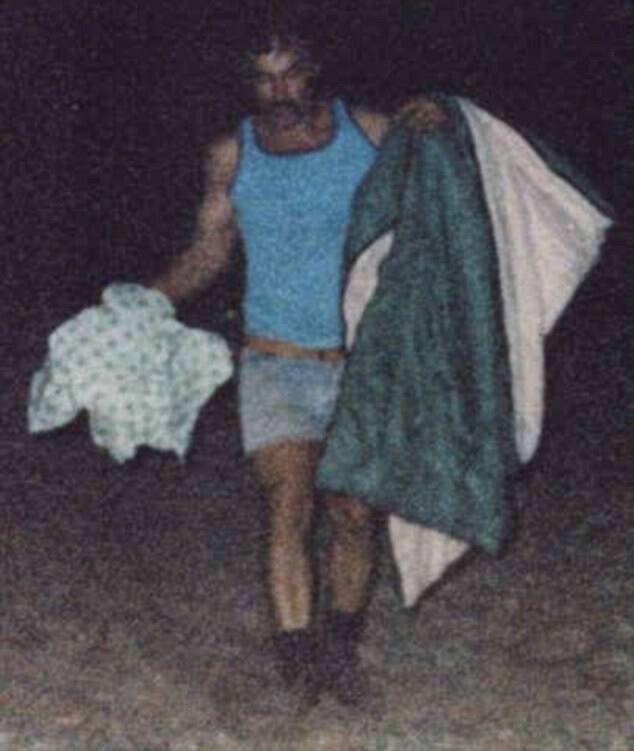

Daily MailA photo of Ivan Milat carrying the sleeping bag of Deborah Everist was among the damning evidence against him.

Authorities counted that between 1989 and 1992, the killer acted every 12 months. His target of choice was young travelers — both men and women — whom he picked up as they tried to grab rides from strangers from Sydney to Melbourne.

The media frenzy soon conjured up past reports about the Milat brothers who were known to possess firearms and lived about an hour away from the Belanglo forest.

However, authorities did not have any evidence that would warrant a search of the Milats or their property where Ivan Milat was still living with his mother.

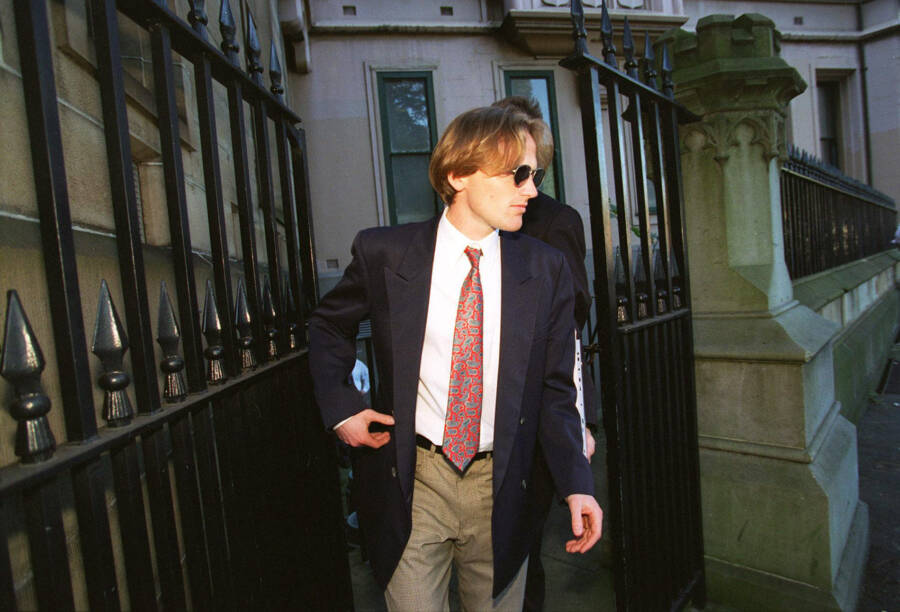

Fairfax Media via Getty Images/Fairfax Media via Getty Images via Getty ImagesThe information provided by Backpacker Murderer survivor, Paul Thomas Onions, proved integral to putting Ivan Milat behind bars.

Among the flood of tipsters eventually came news from a British man named Paul Onions, an ex-Navy member who had backpacked around Australia years prior. He told Australian investigators that a man had tried to kill him during his travels and that he believed this was the same man responsible for the other Backpacker Murders.

The man introduced himself to Onions as “Bill” and offered Onions a lift while he was backpacking along the highway, but Onions soon grew suspicious when the driver pulled off the road.

Later, the man stopped his car in a secluded area miles away from the highway where he pulled out a gun and rope.

“I just thought, ‘This is it… run or die’, so I undid my seatbelt and jumped straight out of the vehicle and ran,” Onions recalled of the incident years later.

The driver fired at Onions as he tried to run across the Hume Highway. Eventually, he flagged down a woman driver, Joanne Berry, yelling and pleading at her for help. Berry helped him to escape. But Onions’ report and Berry’s statement about the incident to local police was waved off and forgotten — that is until Onions saw the news about the Belanglo Backpacker Murders.

Fairfax Media via Getty Images/Fairfax Media via Getty Images via Getty ImagesDetectives take then-suspected backpacker killer Ivan Milat into custody in 1994.

Australian authorities flew Onions in from London to Sydney to identify the man who had tried to kidnap and murder him. Out of 13 photos of suspects, Onions identified his almost-killer as suspect number four: Ivan Milat.

The Eventual Capture Of Ivan Milat

Meanwhile, authorities reached out to the two women who had been hitchhiking in 1977 near the forest and had narrowly escaped murder at the hands of an anonymous man with “black straggly hair.” After being shown a series of photos which included both Ivan Milat and his brother Richard, one of the women identified the brothers.

Together with Milat’s 1971 rape charge from two female backpackers, authorities believed they’d found their Backpacker Murderer. They placed an intercept on the Milat’s Sydney home, which was owned and shared between Ivan Milat and his sister, Shirley Soire, who many said was in some way involved in the murders as well.

“Shirley was in on it,” the Milat’s youngest brother, George, reported. “I can’t really say Shirley did (commit murders), all I can do is say she was involved.”

Soire and Milat also allegedly had a sexual relationship since the 1950s.

Fairfax Media via Getty Images/Fairfax Media via Getty Images via Getty ImagesIvan Milat’s mother watches as her son is taken into custody.

Investigation efforts culminated in a search operation of Milat’s home on May 22, 1994. Teams of armed police dressed in bulletproof vests surrounded the perimeter while, according to Small, Milat laughed and mocked the lead negotiator as if all of it was a joke.

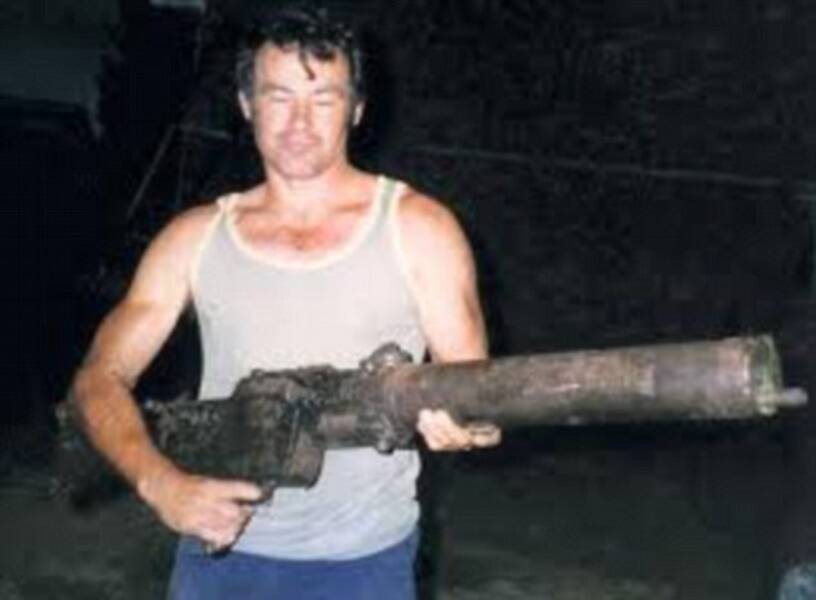

Once the team of armed police was able to place Ivan Milat under arrest, they searched the premises and found a postcard from someone from New Zealand who referred to Milat as “Bill,” the same firearms cartridges and electrical tape found at some of the murder scenes, and Indonesian currency. Milat had never traveled to Indonesia but victims Neugebauer and Habschied had spent time there right before traveling to Australia.

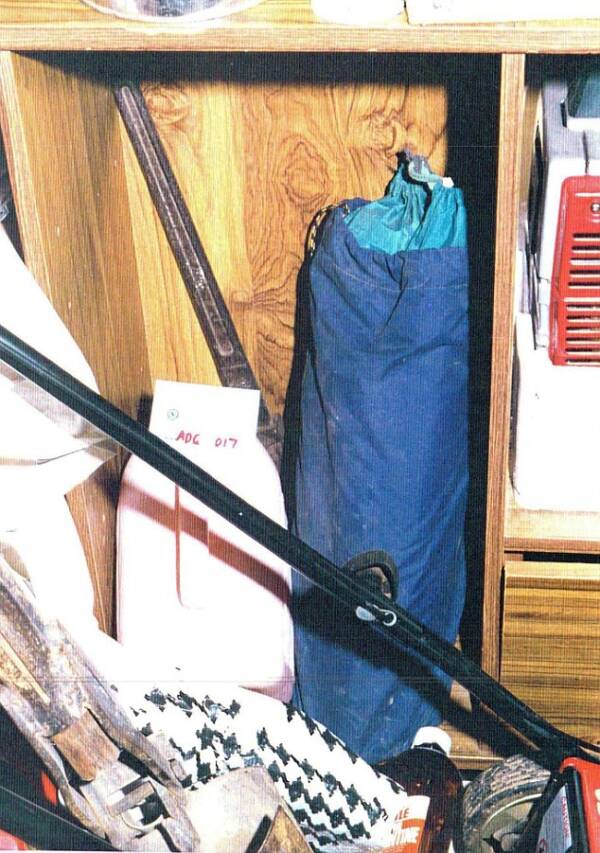

But the motherload was no doubt the backpacking items and other equipment that investigators uncovered around the house and even inside the home’s walls.

The items matched the belongings of several of the Belanglo forest victims. Smalls described the discovery as an “Aladdin’s cave of evidence.”

Daily MailOne of Ivan Milat’s victims, Simone Schmidl’s, sleeping bag was among the sinister trophies found lying around Ivan Milat’s home.

As investigators continued to rummage through the house, an eerie thought crept into Smalls’ mind:

“The house was jointly owned by Ivan and his sister, but the way Ivan’s things — including weapons, ammunition, clothing and other property apparently linked to the Backpacker Murders — were strewn around the property, it made it look as if the house was Ivan’s alone. I left the house convinced that [forensic psychiatrist Rod] Milton had been right in his assessment that control, possession, and domination were the driving forces behind Ivan’s life.”

After a trial that lasted weeks, the Backpacker Murderer was sentenced to seven life sentences, one for each of Ivan Milat’s victims found in Belanglo, plus six years for the abduction of Onions, without the possibility of parole.

Although the killer was put behind bars, mystery still shrouds the case of the Backpacker Murders. Namely, how Milat managed to pull off some of the murders on his own, which has led to the theory that he may have operated with an accomplice, like his brother Richard, even though no tangible evidence against him has ever been discovered.

Milat’s Quest To Clear His Name

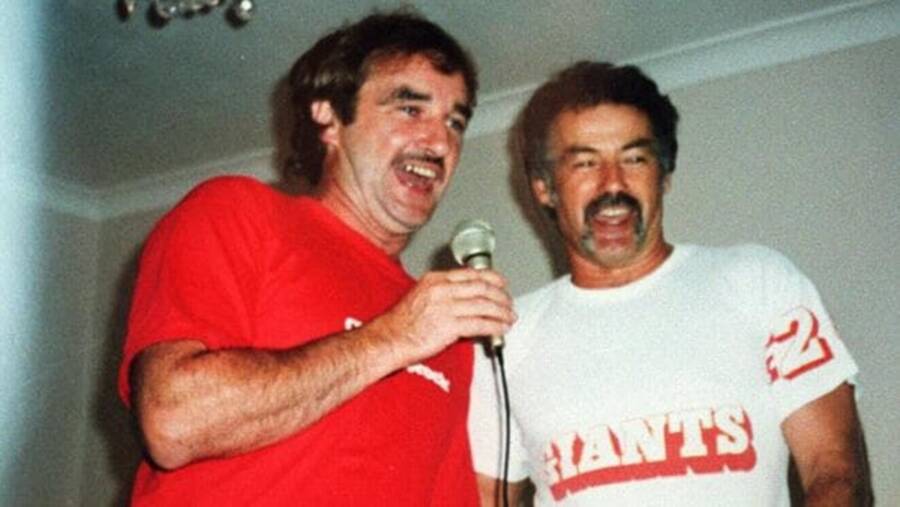

News Corp AustraliaSome suspect that Ivan Milat’s brother, Richard (left), was involved in some way with the Backpacker Murders.

To this day, police remain unsure as to whether they’ve uncovered all of Ivan Milat’s victims. They suspect a slew of missing-persons cases dating back to the early 1970s could also have been his doing.

Just because the Backpacker Murderer was caught, however, doesn’t mean he was taken out of the spotlight. In 1997, Milat attempted to escape prison alongside a convicted drug dealer. The two failed and the drug dealer hung himself in his cell the next day.

Milat was consequently transferred to the maximum-security super-prison in Goulburn, New South Wales.

Ivan Milat maintained his innocence until the end, working on a crusade to clear his name ever since he first stepped foot in jail.

He wrote numerous letters to reporters and Australian newspapers claiming his innocence, including a letter, addressed to the Sydney Morning-Herald. At one point, he printed out the phrase “Ivan is innocent” using a prison Dymo labeling machine and plastered the labels on the prison walls.

In his more extreme endeavors, Milat wrote to the NSW Supreme Court, the DNA Review Panel, and the Attorney-General’s office to review his trial, and he even cut off his little finger with a plastic knife so that he could mail it into the High Court to force an appeal on his case.

Eventually, Ivan Milat was diagnosed with oesophageal cancer and was moved to the medical ward of Long Bay Correctional Centre for chemotherapy.

On October 27, 2019, the disease took his life at age 74.

The True Story Of Wolf Creek

As Ivan Milat has since become known as one of Australia’s worst serial killers, he’s also become the focus of true crime entertainment. For instance, the gory murder movie Wolf Creek became the first on-screen adaptation of Milat’s murders in 2005.

Wolf Creek itself is a real-life popular tourist site in western Australia, but the killings said to have occurred there were made up. Elements from Milat’s Backpacker Murders and murders by killer Bradley Murdoch in 2001 were used to create the film’s story.

“Look at how big Australia is. How do you find a body? That’s what Wolf Creek taps into,” director Greg McLean said.

According to McLean, the film’s main character, Mick, is a composite of both Ivan Milat and Bradley John Murdoch, who was charged for the murder of British backpacker Peter Falconio in 2005.

“So it’s combined elements of those true characters, and then took a lot of Australian archetypal characters and cultural mythology, like Crocodile Dundee and Steve Irwin, and wove those characters into a combination to come up with the character… It’s a kind of an interesting combination of those two things; the iconography and the repressed side of the country,” McLean added.

The Grim Legacy Of Ivan Milat’s Murders

News Corp AustraliaMargaret Milat with one of her other sons.

Meanwhile, Ivan Milat’s family has been publicly divided by his actions.

Some members, like his brother Boris, have spoken against Milat’s crimes while others still defend him. One of his biggest supporters is his nephew Alistair Shipsey.

Shipsey has spoken to the press on a number of occasions to declare his uncle’s innocence. After the suicide of Shipsey’s father when he was 16, Shipsey said that his uncle had helped to pay for part of the funeral and headstone. They stayed close ever since.

“I am his oldest nephew and we have always been close,” Shipsey once said. “He’s a good person, with a big heart — he was a tower of strength.”

Then, there is Ivan Milat’s mother Margaret Milat, who, according to one Milat brother, is the only person to whom the Backpacker Murderer has confessed. But the Milat matriarch has always maintained that her son wasn’t guilty in public and refused to say otherwise.

But Ivan Milat’s biggest legacy, perhaps, is that his murderous tendencies were apparently passed on to another generation of the family.

In 2012, Ivan Milat’s great-nephew Matthew Milat and his friend Cohen Klein were sentenced to 43 years and 32 years in prison, respectively, for the murder of their classmate, David Auchterlonie, on his 17th birthday.

Milat and Klein had lured the teenager to the Belanglo forest — the same place where Matthew Milat’s great-uncle had committed those horrendous crimes decades ago — with the promise of smoking weed and drinking. Instead, they murdered the birthday boy with an ax.

Even after his death, Ivan Milat casts a shadow of horror over Australia.