The dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral (undamaged) stands out among the flames and smoke of surrounding buildings during heavy attacks of the German Luftwaffe on December 29, 1940 in London, England.

In the summer and fall of 1940, German and British air forces clashed in the skies over the United Kingdom, locked in the largest sustained bombing campaign to that date.

Victory for the Luftwaffe in the air battle would have exposed Great Britain to invasion by the German army, which was then in control of the ports of France only a few miles away across the English Channel.

In the event, the battle was won by the Royal Air Force (RAF) Fighter Command, whose victory not only blocked the possibility of invasion but also created the conditions for Great Britain’s survival, for the extension of the war, and for the eventual defeat of Nazi Germany.

On July 16, 1940, Hitler issued a directive ordering the preparation and, if necessary, the execution of a plan for the invasion of Great Britain.

But an amphibious invasion of Britain would only be possible, given Britain’s large navy, if Germany could establish control of the air in the battle zone.

To this end, the Luftwaffe chief, Göring, on August 2 issued the “Eagle Day” directive, laying down a plan of attack in which a few massive blows from the air were to destroy British air power and so open the way for the amphibious invasion, termed Operation “Sea Lion”.

A formation of low-flying German Heinkel He 111 bombers flies over the waves of the English Channel in 1940.

The forces engaged in the battle were relatively small. The British disposed of some 600 frontline fighters to defend the country.

The Germans made available about 1,300 bombers and dive bombers, and about 900 single-engined and 300 twin-engined fighters.

These were based in an arc around England from Norway to the Cherbourg Peninsula in northern coastal France.

The preliminaries of the Battle of Britain occupied June and July 1940, the climax August and September, and the aftermath—the so-called Blitz—the winter of 1940–41.

In the campaign, the Luftwaffe had no systematic or consistent plan of action: sometimes it tried to establish a blockade by the destruction of British shipping and ports; sometimes, to destroy Britain’s Fighter Command by combat and by the bombing of ground installations; and sometimes, to seek direct strategic results by attacks on London and other populous centers of industrial or political significance.

Three anti-aircraft guns flash in the dark in London, on September 20, 1940, throwing shells at raiding German planes. Shells in stacked rows behind the guns leap about as the concussions from the firing loosen them.

The British, on the other hand, had prepared themselves for the kind of battle that in fact took place.

Their radar early warning, the most advanced and the most operationally adapted system in the world, gave Fighter Command adequate notice of where and when to direct their fighter forces to repel German bombing raids.

The Spitfire, moreover, though still in short supply, was unsurpassed as an interceptor by any fighter in any other air force.

These London schoolchildren are in the midst of an air raid drill ordered by the London Board of Education as a precaution in case an air raid comes too fast to give the youngsters a chance to leave the building for special shelters, on July 20, 1940. They were ordered to go to the middle of the room, away from windows, and hold their hands over the backs of their necks.

The British fought not only with the advantage—unusual for them—of superior equipment and undivided aim but also against an enemy divided in object and condemned by circumstance and by lack of forethought to fight at a tactical disadvantage.

The German bombers lacked the bomb-load capacity to strike permanently devastating blows and also proved, in daylight, to be easily vulnerable to the Spitfires and Hurricanes.

Britain’s radar, moreover, largely prevented them from exploiting the element of surprise.

The German dive bombers were even more vulnerable to being shot down by British fighters, and long-range fighter cover was only partially available from German fighter aircraft since the latter were operating at the limit of their flying range.

A German twin propelled Messerschmitt BF 110 bomber, nicknamed “Fliegender Haifisch” (Flying Shark), over the English Channel, in August of 1940.

The German air attacks began on ports and airfields along the English Channel, where convoys were bombed and the air battle was joined.

In June and July 1940, as the Germans gradually redeployed their forces, the air battle moved inland over the interior of Britain.

On August 8 the intensive phase began when the Germans launched bombing raids involving up to nearly 1,500 aircraft a day and directed them against the British fighter airfields and radar stations.

In four actions, on August 8, 11, 12, and 13, the Germans lost 145 aircraft as against the British loss of 88.

By late August the Germans had lost more than 600 aircraft, the RAF only 260, but the RAF was losing badly needed fighters and experienced pilots at too great a rate, and its effectiveness was further hampered by bombing damage done to the radar stations.

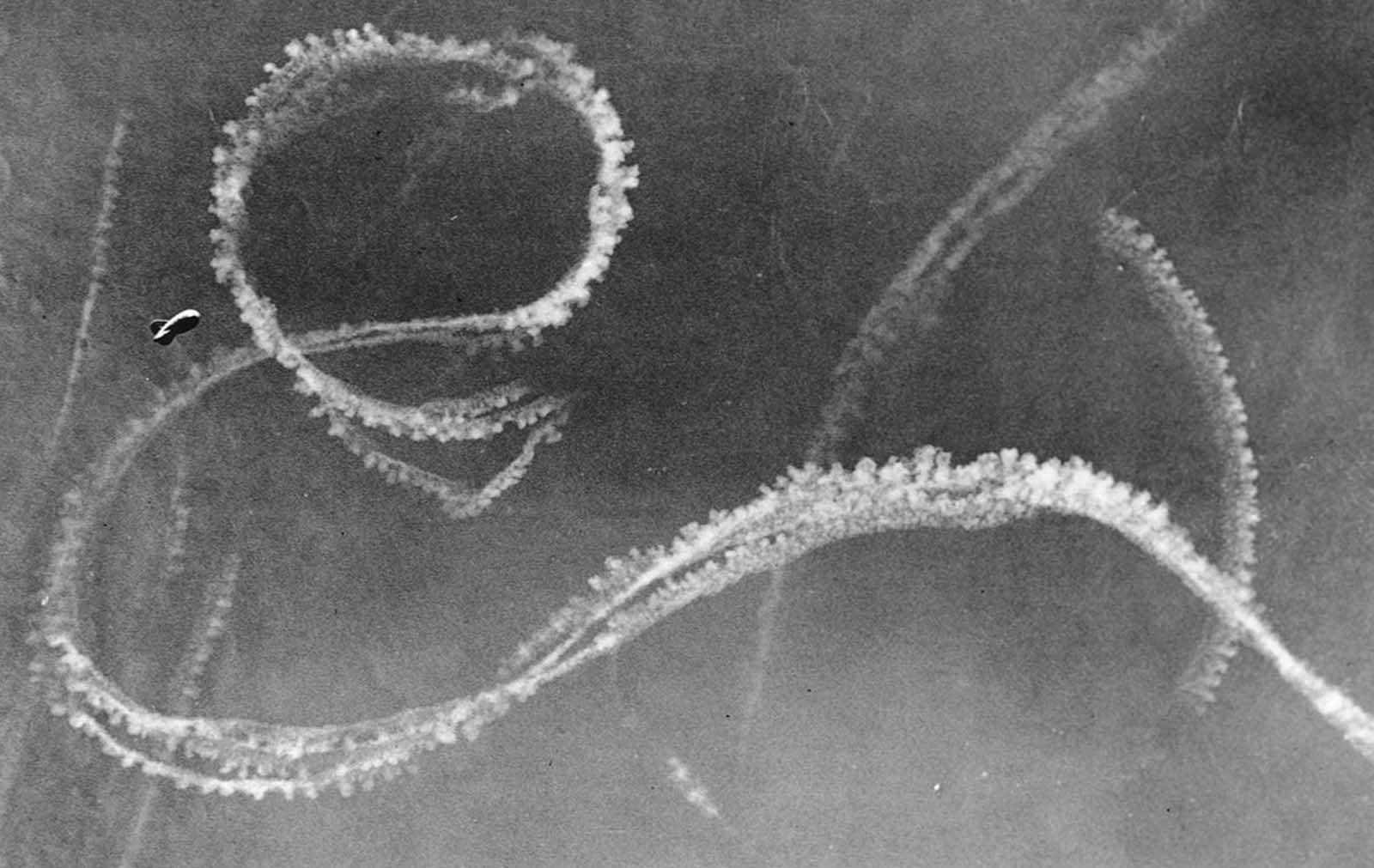

The condensation trails from German and British fighter planes engaged in an aerial battle appear in the sky over Kent, along the southeastern coast of England, on September 3, 1940.

At the beginning of September, the British retaliated by unexpectedly launching a bombing raid on Berlin, which so infuriated Hitler that he ordered the Luftwaffe to shift its attacks from Fighter Command installations to London and other cities.

To avoid the deadly RAF fighters, the Luftwaffe shifted almost entirely to night raids on Britain’s industrial centers.

The “Blitz,” as the night raids came to be called, was to cause many deaths and great hardship for the civilian population, but it contributed little to the main purpose of the air offensive—to dominate the skies in advance of an invasion of England.

Fires set by bursting German bombs lit up the docks along the River Thames in London, on September 7, 1940, and brought into vivid relief the merchant ships lying alongside the many docks which line London’s busy port. British sources said the bombing that night was the heaviest of the war to date.

A great column of smoke billowing upward from a fire started at Plymouth, South West England, in November 1940, as a result of heavy enemy bombardment.

On September 3 the date of invasion had been deferred to September 21, and then on September 19, Hitler ordered the shipping gathered for Operation Sea Lion to be dispersed. British fighters were simply shooting down German bombers faster than German industry could produce them.

The Battle of Britain was thus won, and the invasion of England was postponed indefinitely by Hitler. The British had lost more than 900 fighters but had shot down about 1,700 German aircraft.

During the following winter, the Luftwaffe maintained a bombing offensive, carrying out night-bombing attacks on Britain’s larger cities. By February 1941 the offensive had declined, but in March and April there was a revival, and nearly 10,000 sorties were flown, with heavy attacks made on London. Thereafter German strategic air operations over England withered.

The tail and part of the fuselage of a German Dornier plane landed on a London rooftop shown Sept. 21, 1940, after British fighter planes shot it down on September 15. The rest of the raiding plane crashed near Victoria Station.

The Battle of Britain marked the first major defeat of Hitler’s military forces, with air superiority seen as the key to victory.

Pre-war theories had led to exaggerated fears of strategic bombing, and UK public opinion was buoyed by coming through the ordeal.

For the RAF, Fighter Command had achieved a great victory in successfully carrying out Sir Thomas Inskip’s 1937 air policy of preventing the Germans from knocking Britain out of the war.

Churchill concluded his famous 18 June ‘Battle of Britain’ speech in the House of Commons by referring to pilots and aircrew who fought the Battle: “… if the British Empire and its Commonwealth lasts for a thousand years, men will still say, ‘This was their finest hour’“.

Workmen fit a set of paraboloids in a sound detector for use by anti-aircraft batteries guarding England, in a factory somewhere in England, on July 30, 1940.

The British victory in the Battle of Britain was achieved at a heavy cost.

Total British civilian losses from July to December 1940 were 23,002 dead and 32,138 wounded, with one of the largest single raids on 19 December 1940, in which almost 3,000 civilians died.

With the culmination of the concentrated daylight raids, Britain was able to rebuild its military forces and establish itself as an Allied stronghold, later serving as a base from which the Liberation of Western Europe was launched.

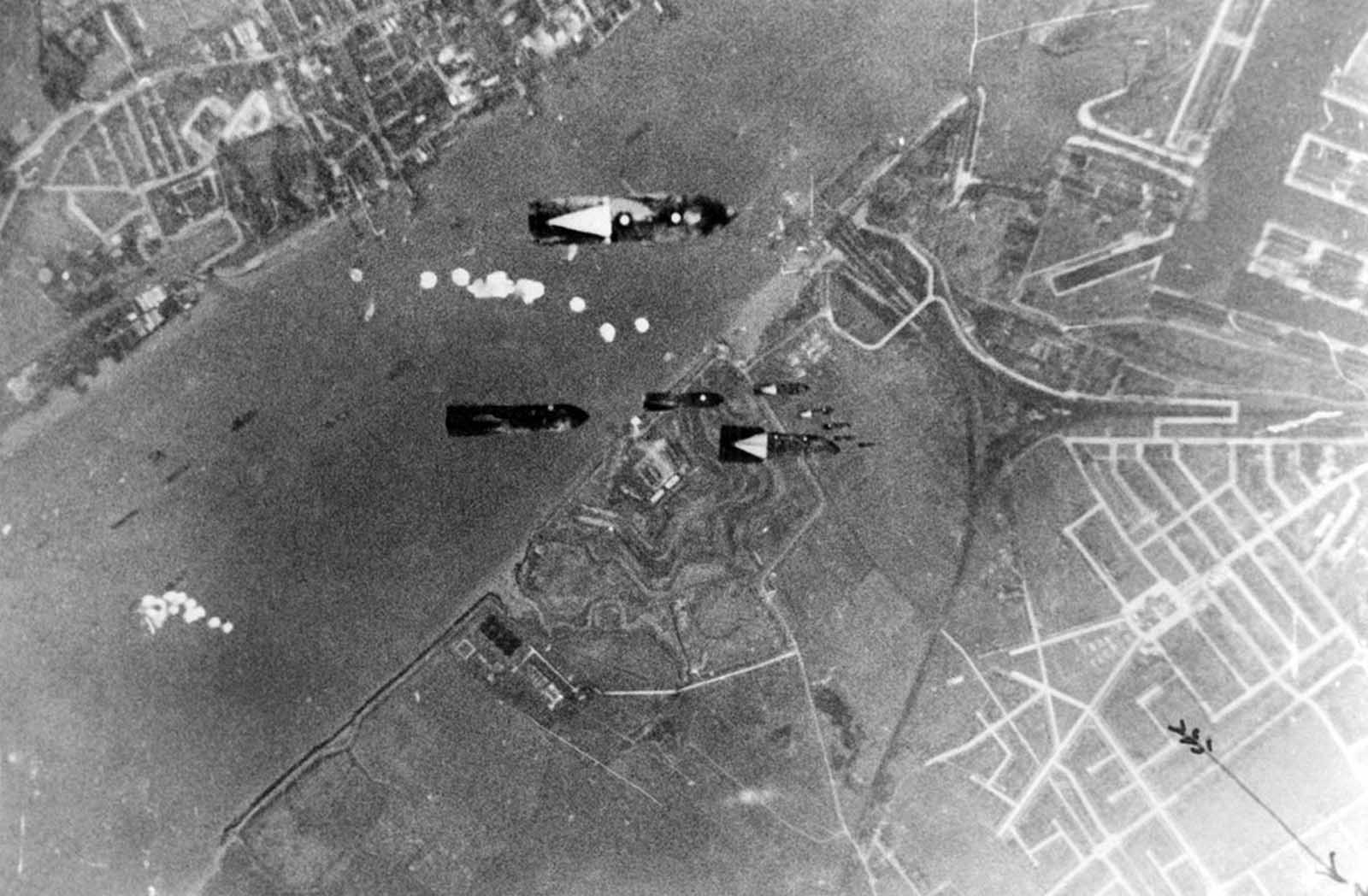

The biggest shipping center for London’s food-supplies, Tilbury, has been the target of numerous German air attacks. Bombs dropping on the port of Tilbury, on October 4, 1940. The first group of bombs will hit the ships lying in the Thames, the second will strike the docks.

Two German Luftwaffe Ju 87 Stuka dive bombers return from an attack against the British south coast, during the Battle for Britain, on August 19, 1940.

A bomb is fitted to the wings of a British raider prior to the start of an assault on Berlin, on October 24, 1940.

A ninety-minute exposure taken from a Fleet Street rooftop during an air raid in London, on September 2, 1940. The searchlight beams on the right had picked up an enemy raider. The horizontal marks across the image are from stars and the small wiggles in them were caused by the concussions of anti-aircraft fire vibrating the camera. The German pilot released a flare, which left a streak across the top left, behind the steeple of St. Bride’s Church.

People shelter and sleep on the platform and on the train tracks, in Aldwych Underground Station, London, after sirens sounded to warn of German bombing raids, on October 8, 1940.

The Palace of Westminster in London, silhouetted against the light from fires caused by bombings.

The force of a bomb blast in London piled these furniture vans atop one another in a street after a raid on December 5, 1940.

This smiling girl, dirtied but apparently not injured, was assisted across a London street on October 23, 1940, after she was rescued from the debris of a building damaged by a bomb attack in a German daylight raid.

Firemen spray water on damaged buildings, near London Bridge, in the City of London on September 9, 1940, after a recent set of weekend air raids.

Hundreds of people, many of whom have lost their homes through bombing, now use the caves in Hastings, a south-east English town as their nightly refuge. Special sections are reserved for games and recreation, and several people have “set up house”, bringing their own furniture and sleeping on their own beds. Photo taken on December 12, 1940.

Undaunted by a night of German air raids in which his store front was blasted, a shopkeeper opens up the morning after for “business as usual” in London.

All that remains of a German bomber brought down on the English south-east coast, on July 13, 1940. The aircraft is riddled with bullet holes and its machine guns were twisted out of action.

British workers in a salvage yard break up the remains of wrecked German raiders which were shot down over England, on August 26, 1940.

A huge scrap heap where German planes, brought down over Great Britain, were dumped, photographed on August 27, 1940. The large number of Nazi planes downed during raids on Britain made a substantial contribution to the national scrap metal salvage campaign.

A Nazi Heinkel He 111 bomber flies over London in the autumn of 1940. The Thames River runs through the image.

Mrs. Mary Couchman, a 24-year-old warden of a small Kentish Village, shields three little children, among them her son, as bombs fall during an air attack on October 18, 1940. The three children were playing in the street when the siren suddenly sounded. Bombs began to fall as she ran to them and gathered the three in her arms, protecting them with her body. Complimented on her bravery, she said, “Oh, it was nothing. Someone had look after the children.”

Two barrage balloons come down in flames after being shot by German war planes during an aerial attack over the Kent coast in England, on August 30, 1940.

Air raid damage, including the twisted remains of a double-decker city bus, in the City of London on September 10, 1940.

A scene of devastation in the Dockland area of London attacked by German bomber on September 17, 1940.

An abandoned boy, holding a stuffed toy animal amid ruins following a German aerial bombing of London in 1940.

A German aircraft drops its load of bombs above England, during an attack on September 20, 1940.

One of many fires started in Surrey Commercial Dock, London, on September 7, 1940, after a heavy raid during the night by German bombers.

Fires rage in the city of London after a lone German bomber had dropped incendiary bombs close to the heart of the city on September 1, 1940.

London children enjoy themselves at a Christmas Party, on December 25, 1940, in an underground shelter.

The effects of a large concentrated attack by the German Luftwaffe, on London dock and industry districts, on September 7, 1940. Factories and storehouses were seriously damaged; the mills at the Victoria Docks (below at left) show damage wrought by fire.

The Record Office in London, lit by flames ignited by a German air in 1940.

Princess Elizabeth of England (center), 14-year-old heiress apparent to the British throne, makes her broadcast debut, delivering a three-minute speech to British girls and boys evacuated overseas, on October 22, 1940, in London, England. She is joined in bidding good-night to her listeners by her sister, Princess Margaret Rose.

Soldiers carrying off the tail of a Messerschmitt 110, which was shot down by fighter planes in Essex, England, on September 3, 1940.

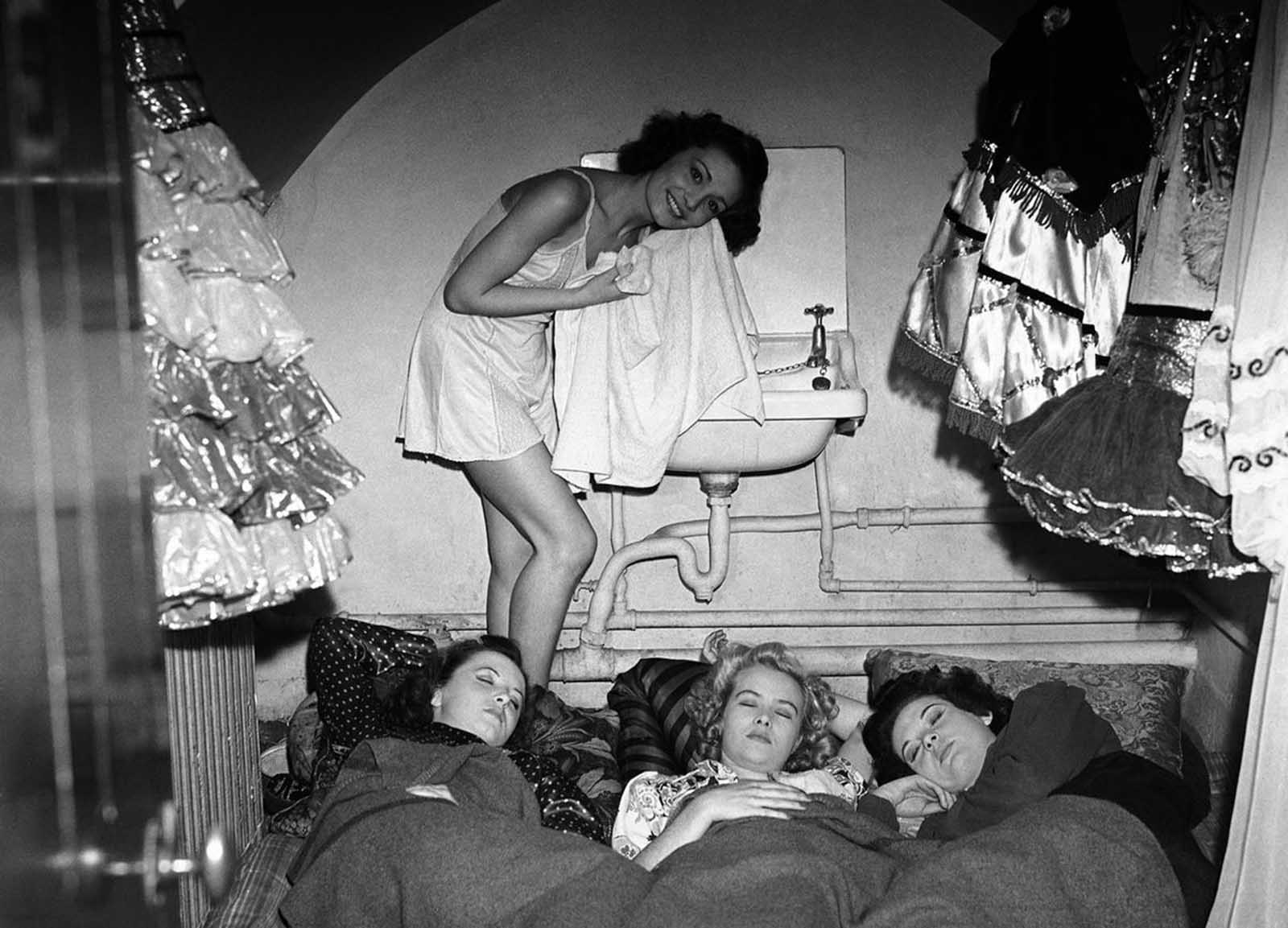

Through bombs and sirens, the Windmill Theatre carried on providing music, revue, and ballet performances for the people of wartime London. The artists sleep on mattresses in their dressing rooms, living and eating on the premises. Here, a scene behind the scenes shows one of the girls having a wash while the others sleep soundly surrounded by their picturesque costumes, after the show on September 24, 1940, in London.

A German raid smashed this hall in an undisclosed London district, on October 16, 1940.

A huge crater was made in a road at Elephant & Castle, London on September 7, 1940, after a night raid on London.

Two girls on the south coast of England look out toward the beach through a barbed wire fence constructed as part of Britain’s coastal defenses.

The artist Ethel Gabain, newly appointed by the Ministry of Information to make historical war pictures, at work among bombed ruins in the East End of London on November 28, 1940.

A forward machine gunner sits at his battle position in the nose of a German Heinkel He 111 bomber, while en route to England in November of 1940.

A boy sits amid the ruins of a London bookshop following an air raid on October 8, 1940, reading a book titled “The History of London.