She claimed to be the final descendant of the last Incan Emperor, Atahualpa — a claim the Peruvian government backed in 1946 — and she allegedly learned to sing from “the creatures of the forest.” Yma Sumac didn’t just hit octaves. She knocked them out of the park with a growl, and took them for a ride around the Milky Way. For opera aficionados, the Peruvian soprano goes down in history as one of the most talented, and wonderfully weird performers in modern history.

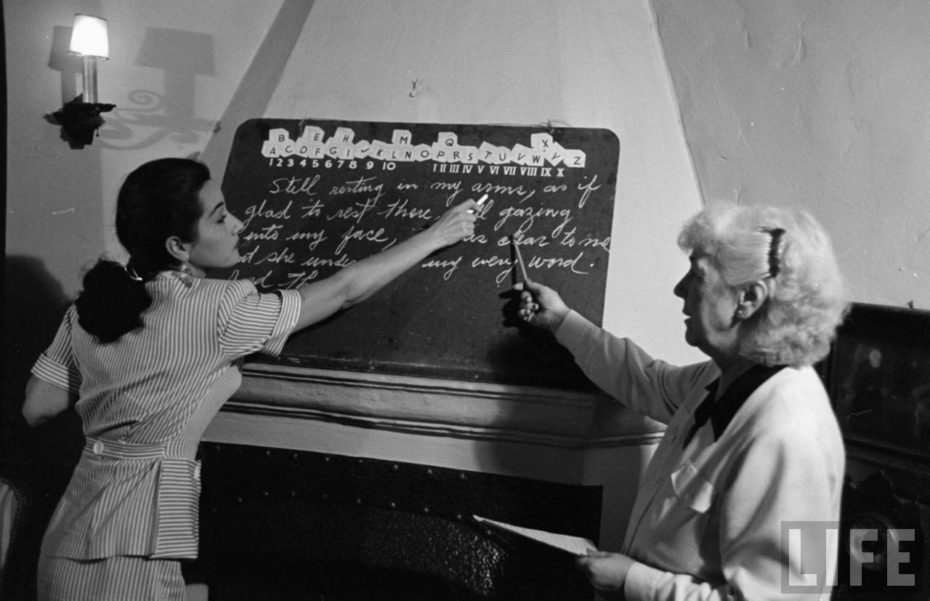

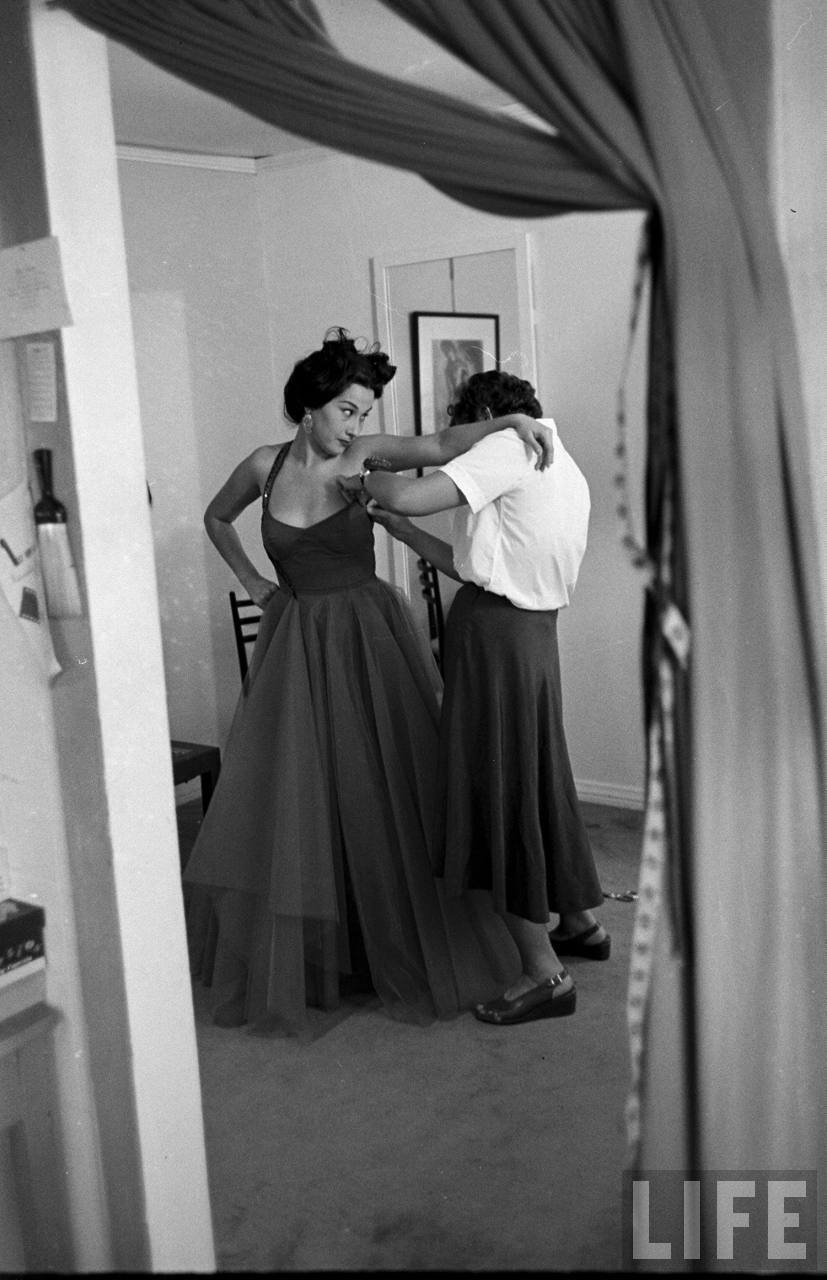

She was born in 1922 as Zoila Augusta Emperatriz Chavarri del Castillo in the misty Andes mountains. When she moved to New York in 1949, Sumac was singing in hole-in-the-wall-joints in the Greenwich Village.

In other words, Sumac carved out an empowering place for herself as a minority artist in the 1950s, arguably the most vanilla period of US history, to ruffle America’s feathers for the better.

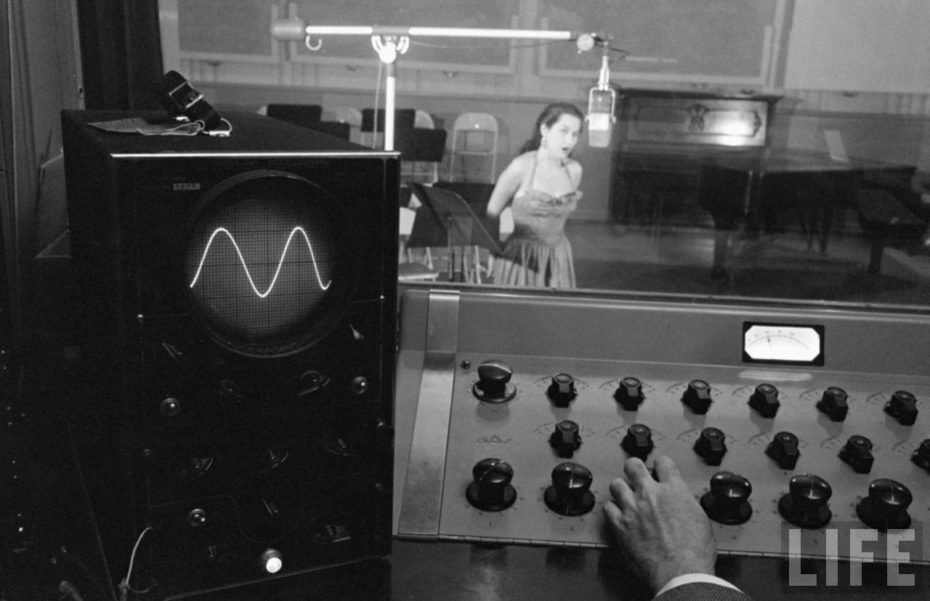

Some reports claimed she had a six-and-a-half octave range, in lieu of the average three. And that made her nothing short of a miracle, and she soon signed with Capitol Records. Bruce Springsteen once declared: “It takes only a fraction of a second to succumb to her unique voice.” Audio restoration expert John H. Haley said her voice had, “the bright penetrating peal of a true coloratura soprano,” but in a place of “alluring sweet darkness…virtually unique in our time.”

One listen to a Sumac track, and you’ll feel as if your ears are on an operatic acid trip; in a single breath her voice can become a human-didjeridoo, graceful cockatoo, or giddy diva (her 1971 album, Miracles, is also unabashedly psychedelic and worth a listen):

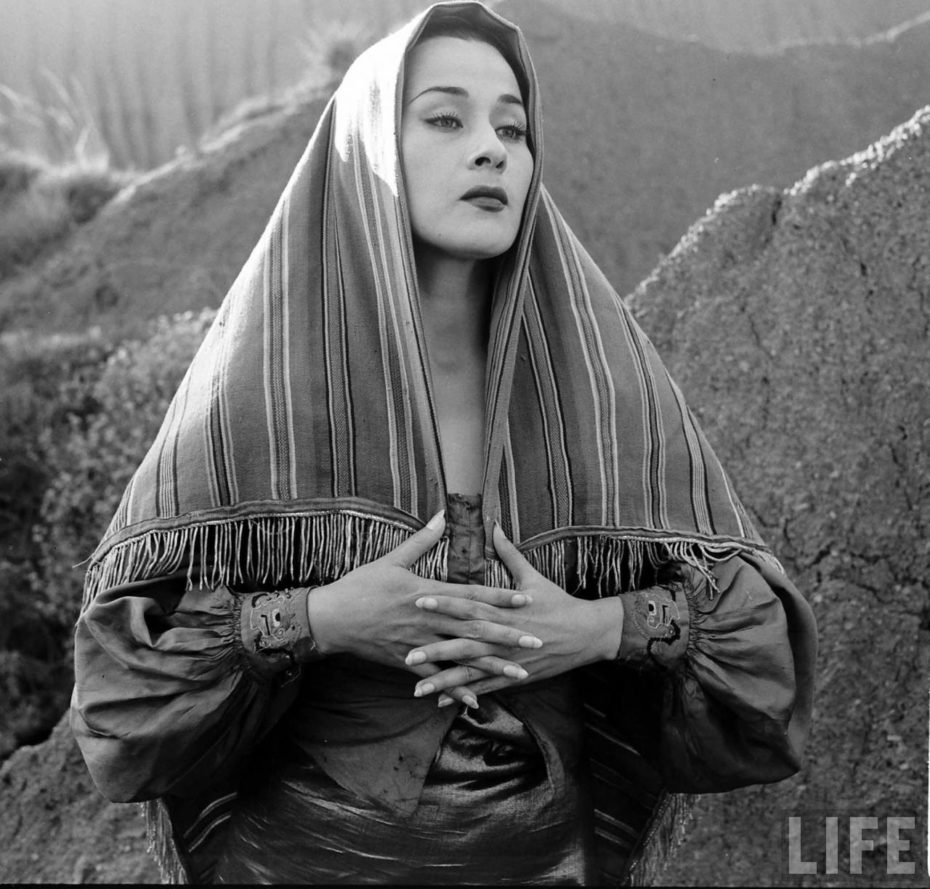

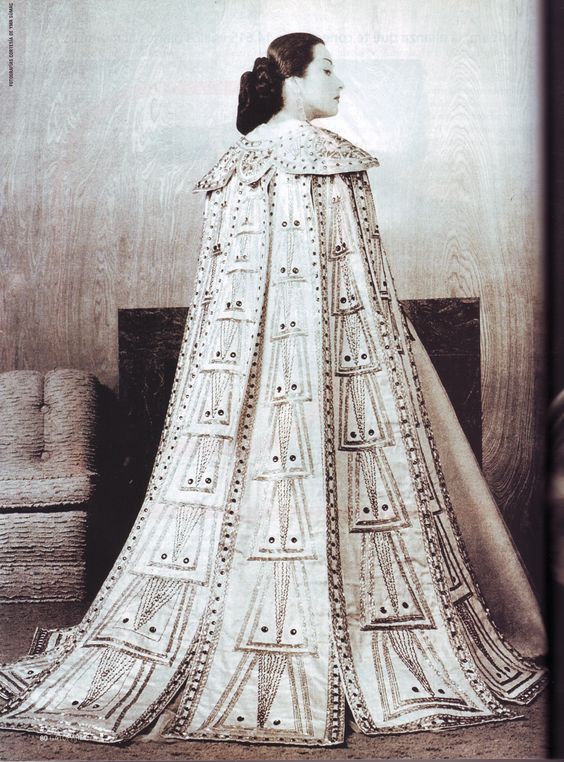

Capitol played up her heritage, and her long black hair was often woven into braids, her eyes made up in kohl and her body dripping in silver jewellery, or her trademark medallion necklace…

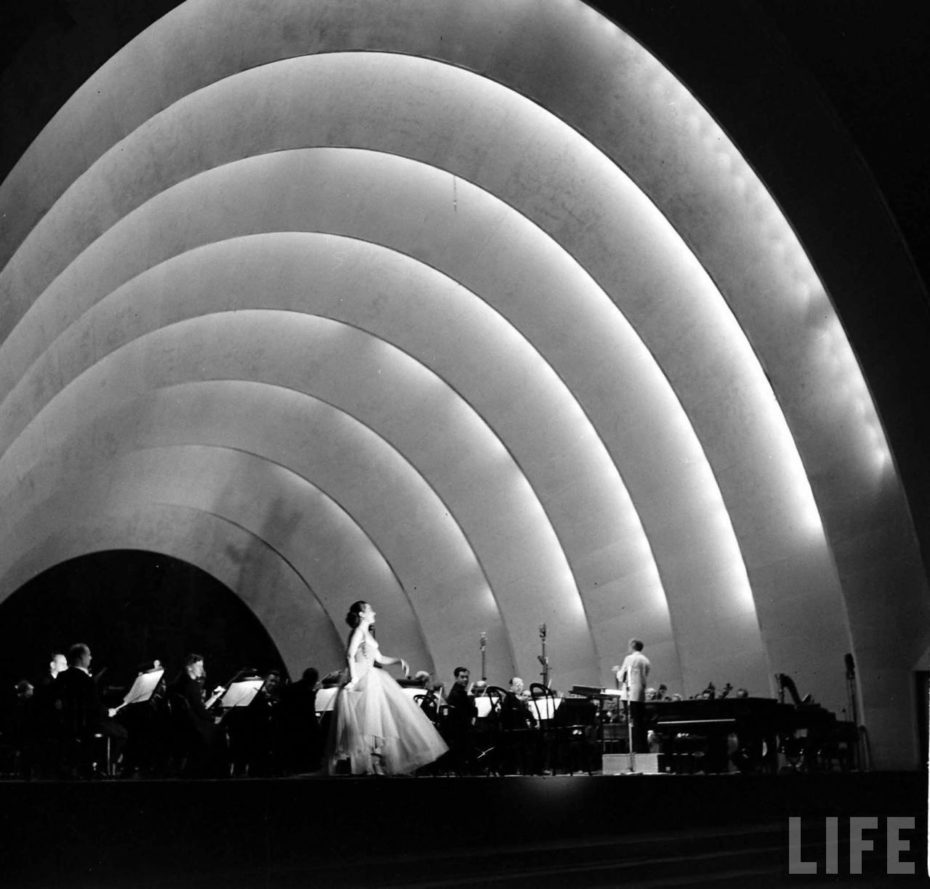

By 1950, her album “Voice of the Xtabay” transformed her into an exotic American Sweetheart, performing at places like the Hollywood Bowl and Carnegie Hall. At one point, she was even outselling Bing Crosby, which is really saying something for a woman who was basically the Björk of the opera scene.

Next she was off to Europe to perform for the Queen at the Royal Albert Hall followed by more than 80 concerts in London and 16 concerts in Paris. A second tour took her to the Far East: Persia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Burma, Thailand, Sumatra, the Philippines, and Australia. She was so popular in countries such as Greece, Israel and Russia that two-week stays turned into six months residencies.

In 1954, she made her cinema debut in Secret of the Incas opposite Charlton Heston. The combination of her extraordinary voice, “exotic” looks, and stage personality made her a hit with American audiences.

She made some Hollywood-style versions of Incan and South American folk songs, starred on Broadway’s 1951 spectacle, Flahooley, and was earning as much as $25K per week on the Las Vegas circuit. She became a U.S. citizen on July 22, 1955.

Yet, examined in the rearview mirror of 2018, Sumac’s success can feel like a double-edged sword. Capitol marketed her as “the most elusive of all women…a virgin who might have consumed your nights with tender caresses [and] now seems less than the dry leaves of winter.” They took Sumac’s knack for camp, and often pushed it into straight-up exotic fetishisation. It was a complex platform to be standing on for the singer, but certainly better than none.

In 1996, the Tampa Tribune called her “tribalisms” a natural fit for “a space-age bachelor pad,” and called her album “a South American travelogue scripted by Disney, directed by Dali.” She was wildly colourful, but even at the height of her fame, kept to herself.

She fell out of favour in the 1960s, but Sumac’s voice continued to find a place on Disney film soundtracks such as Sleeping Beauty, and she gradually acquired a cult following. In 1971, she released a rock album and at recorded a German “techno” dance record in the 80s. When she died in 2008 at the age of 85, Sumac took her secrets to the grave. “She’s a very eccentric woman,” a representative of Sumac told the LA Times in 2007, “Her whole career and life is based on her mystery, and so the facts and fiction is a fine line with her.”