Richard Trevithick was a pioneer in early steam engine technology who successfully tested the first steam-powered locomotive, but he ended his life in obscurity.

Trevithick was born in Illogan, Cornwall, in 1771, the son of a Cornish mining family. Dubbed “The Cornish Giant” for his height—he stood 6’2”, remarkably tall for the time—and for his athletic build, Trevithick was an accomplished wrestler and sportsman, but an unaccomplished scholar.

He did, however, have an aptitude for math. And when he was old enough to join his father in the mining business, it was clear that this aptitude extended to the blossoming field of mine engineering, and especially in the use of steam engines.

Trevithick grew up in the crucible of the Industrial Revolution, surrounded by emerging mining technology. His neighbor, William Murdoch, was pioneering new advances in steam-carriage technology.

Steam engines were also used to pump water out of the mines. Because James Watt already held a number of important steam-engine patents, Trevithick attempted to pioneer steam technology that didn’t rely on Watt’s condenser model.

He succeeded, but not well enough to escape Watt’s lawsuits and personal enmity. And while his use of high-pressure steam represented a new breakthrough, it also drew concerns about its safety. Despite setbacks which gave credibility to those concerns—one accident killed four men—Trevithick continued his work on developing a steam engine that could reliably haul cargo and passengers.

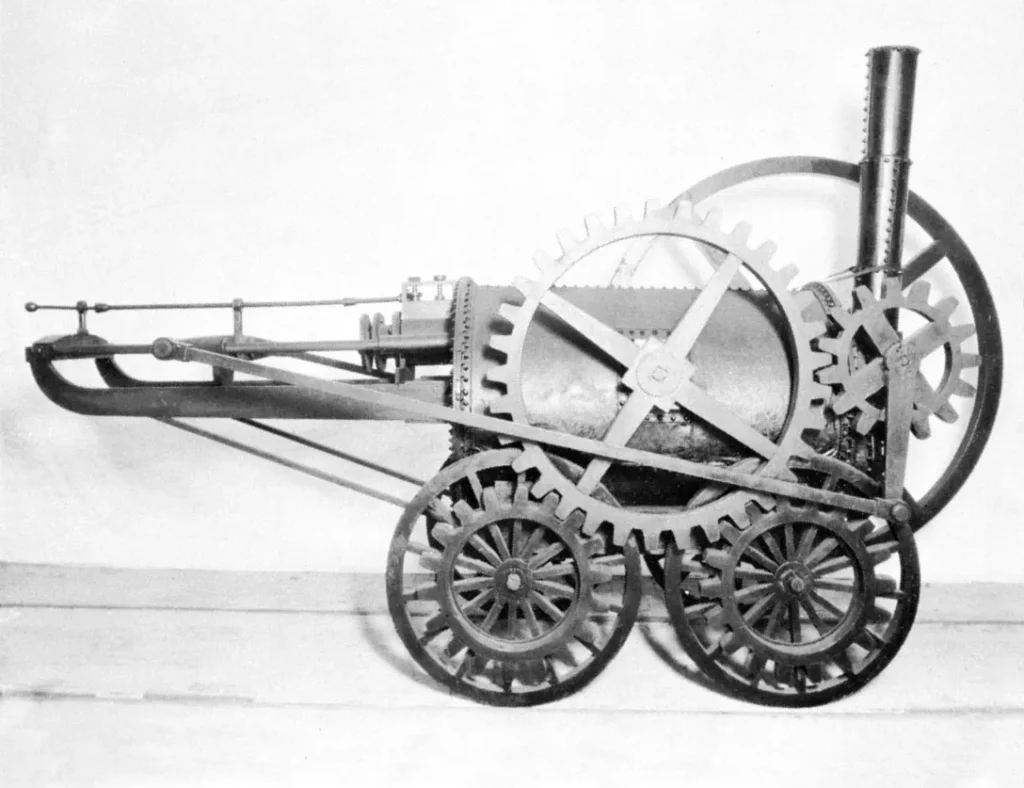

He first developed an engine called The Puffing Devil, that traveled not on rails, but on roads. Its limited ability to retain steam prevented its commercial success, however.

In 1804, Trevithick successfully tested the first steam-powered locomotive to ride on rails. At seven tons, however, the locomotive—called The Pennydarren—was so heavy it would break its own rails.

Drawn to Peru by opportunities there, Trevithick made a fortune in mining—and lost it when he fled that country’s civil war. He returned to his native England, where his early inventions had helped lay the foundation for vast advances in rail locomotive technology.

“I have been branded with folly and madness for attempting what the world calls impossibilities, and even from the great engineer, the late Mr. James Watt, who said to an eminent scientific character still living, that I deserved hanging for bringing into use the high-pressure engine. This so far has been my reward from the public; but should this be all, I shall be satisfied by the great secret pleasure and laudable pride that I feel in my own breast from having been the instrument of bringing forward and maturing new principles and new arrangements of boundless value to my country. However much I may be straitened in pecunary circumstances, the great honour of being a useful subject can never be taken from me, which to me far exceeds riches.”– Richard Trevithick in a letter to Davies Gilbert

Denied his pension by the government, Trevithick caromed from one failed financial endeavor to another. Struck by pneumonia, he died penniless and alone in bed. Only at the last minute did some of his colleagues manage to prevent Trevithick’s burial in a pauper’s grave. Instead, he was interred in an unmarked grave at a burial ground in Dartford.

The cemetery closed not long after. Years later, a plaque was installed near what is believed to be the site of his grave.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-463924189-56b008ae3df78cf772cb3c07.jpg)