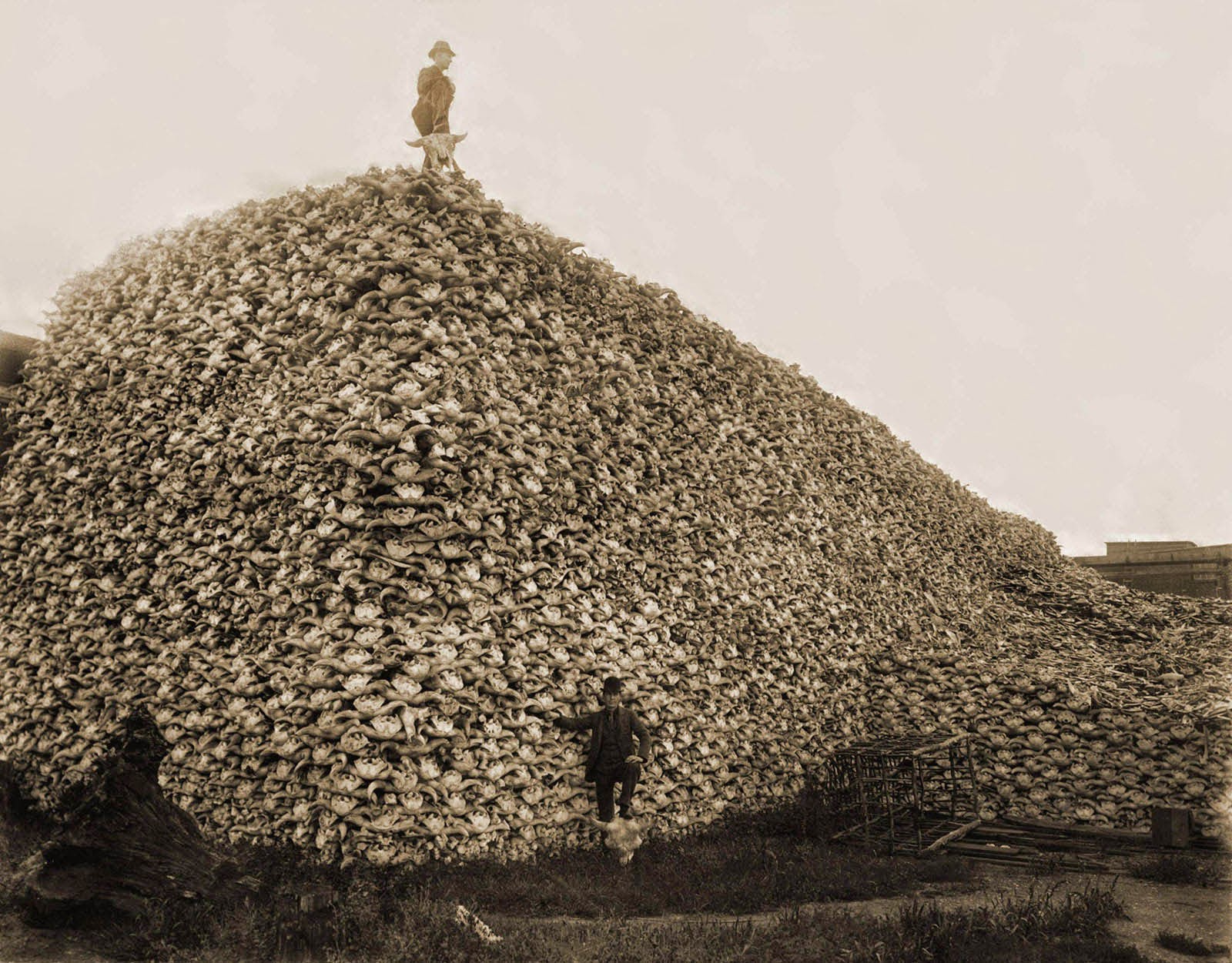

Bison were hunted for their skins, with the rest of the animal left behind to decay on the ground.

Bison were hunted almost to extinction in the 19th century and were reduced to a few hundred by the mid-1880s. They were hunted for their skins, with the rest of the animals left behind to decay on the ground.

Hides were prepared and shipped to the East and Europe (mainly Germany) for processing into leather. Homesteaders collected bones from carcasses left by hunters.

Bison bones were used in refining sugar, and in making fertilizer and fine bone china. Bison bones’ price was from $2.50 to $15.00 a ton.

When modern Europeans arrived in North America, an estimated 50 million bison inhabited the continent. After the great slaughter of American bison during the 1800s, the number of bison remaining alive in North America declined to as low as 541.

During that period, a handful of ranchers gathered remnants of the existing herds to save the species from extinction.

By the 1830s the Comanche and their allies on the southern plains were killing about 280,000 bison a year, which was near the limit of sustainability for that region.

Firearms and horses, along with a growing export market for buffalo robes and bison meat had resulted in larger and larger numbers of bison killed each year.

The railroad industry also wanted bison herds culled or eliminated. Herds of bison on tracks could damage locomotives when the trains failed to stop in time.

Herds often took shelter in the artificial cuts formed by the grade of the track winding through hills and mountains in harsh winter conditions.

As a result, bison herds could delay a train for days, or potentially wrecking the engine. The railroads would hire marksmen to ride their trains and just shoot the bison as the train went by.

Bison bones were used in refining sugar, and in making fertilizer and fine bone china.

The US Army sanctioned and actively endorsed the wholesale slaughter of bison herds.

The federal government promoted bison hunting for various reasons, to allow ranchers to range their cattle without competition from other bovines, and to weaken the North American Indian population.

The US government even paid a bounty for each bison skull recovered. Military commanders were ordering their troops to kill bison — not for food, but to deny Native Americans their own source of food.

One general believed that bison hunters “did more to defeat the Indian nations in a few years than soldiers did in 50 years”.

By 1880, the slaughter was almost over. Where millions of bison once roamed, only a few thousand animals remained.

In 1884 there were around 325 wild bison left in the United States – including 25 in Yellowstone. Before the Europeans arrived in the New World, there were more than 50 million bison in North America.

How many bison skulls might be in the photo?

Hard to tell without being able to see the whole pile. Some rough calculations based on skulls volume and the dimensions of the pile calculate 180,000 skulls on that pile.

Thanks in large part to conservation efforts undertaken by volunteers and later the US government, the American bison was saved from total extinction.

Approximately 500,000 bison currently exist on non-public lands and approximately 30,000 on public lands which include environmental and government preserves.

According to the IUCN, approximately 15,000 bison are considered wild, free-range bison not primarily confined by fencing.