Shortly after John Walter Christie wrecked his V-4-powered racer practicing for the 1906 running of the Vanderbilt Cup, he went to work on his next front-wheel drive race car. He took what he learned from his first V-4 racer and from all his inline racers and applied this knowledge while building the new car. Christie planned to take his new racer to Europe as the first American vehicle to compete in the French Grand Prix. At the same time, Christie wanted to expand his Christie Direct Action Motor Car Company and start producing various automobiles of his design.

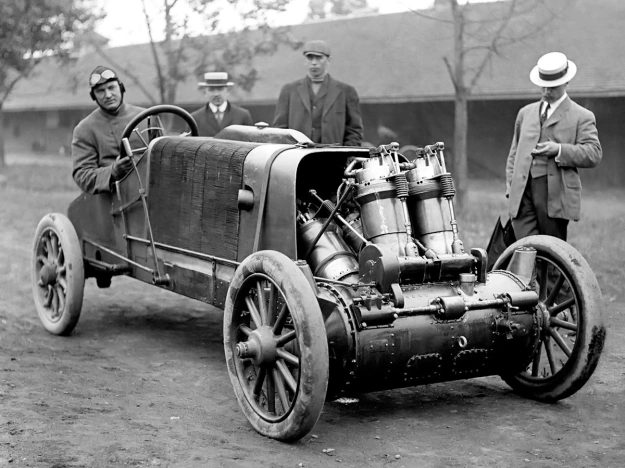

J. Walter Christie’s 1907 V-4 racer under construction at his shop in New York. The drive shaft for the water pump can be seen behind and to the right of the front wheel and extending toward the bottom of the radiator. This shaft was driven from the bevel gear visible in front of the first row of cylinders.

While the 1907 V-4 racer closely resembled the 1906 V-4 racer, it was an entirely new design. The car’s configuration followed that of the previous Christie racers in which the engine was mounted transversely between the two front wheels. The engine’s crankcase formed the car’s front axle and housed its transmission. The car had two forward gears: a normal gear for high-speed operation and a low gear. There was also a reverse gear. Behind the engine was a large radiator in which individual copper tubes were shaped in an inverted “U” and extended from one side of the frame to the other. A header tank was at the upper center of the tubes. The driver and passenger (typically a riding mechanic) sat over the rear axle with the fuel tank behind them.

The engine’s circular crankcase was made of nickel steel and formed an integral part of the chassis. The individual steel cylinders were mounted in two staggered rows on the crankcase. The first row of cylinders leaned back about 10 degrees from vertical, and the second row was angled about 45 degrees from the first row. Each cylinder was surrounded by a copper water jacket. Cooling water exited the top of each cylinder and flowed through a common manifold to the radiator’s header tank. After flowing through the radiator, the cooled water was pulled through a circulation pump and then flowed into the lower part of the cylinder water jacket. The water pump was driven from the camshaft via a long shaft with beveled gears.

Detail view of the V-4 engine and how its crankcase was an integral part of the car’s frame. The cross shaft on the front of the crankcase drove low and reverse gears. Note the camshaft housing in front of the cylinders and the exhaust valve train. The camel hair lining can just be seen on the outer diameter of the flywheel housed in the crankcase. The clutch would be installed between the flywheel and the crankcase.

Each cylinder had one large, mechanically operated exhaust valve. Via a rocker arm and pushrod, all exhaust valves were actuated by a single camshaft mounted on the outside of the crankcase and in front of the first row of cylinders. From the driver’s position, the right side of the camshaft was geared to the crankshaft, and its left side was geared to the water pump drive shaft. Surrounding the exhaust valve were eight atmospheric (automatic) intake valves mounted in a manganese bronze inlet chamber. The incoming air/fuel charge flowed from the Breeze carburetor, which was positioned behind the engine, into a manifold that branched into separate intake pipes for each cylinder. This configuration gave each cylinder a different induction pipe length and led to unequal air/fuel distribution.

Many sources list the bore and stroke as 7-9/32 in (185 mm) and the total displacement as 1,214 cu in (19.9 L). However, the engine actually had a 7.25 in (184 mm) bore and stroke that gave a total displacement of 1,197 cu in (19.6 L). The 185 mm (7-9/32 in) figure probably originated from the European press rounding up the true 7.25 in (184 mm) number. Regardless, the car’s displacement was the largest of any Grand Prix racer before or since. The V-4 engine reportedly produced around 130 hp (97 kW), but it was probably closer to 100 hp (75 kW).

Christie’s V-4 racer with its full engine cowling. It seems the cowling’s grill was quickly cut away to increase airflow through the radiator. Each cylinder had short exhaust stacks, and the front cylinders expelled their exhaust through the top of the cowl.

The stagger of the cylinders allowed the use of a two-throw crankshaft. Two hollow steel connecting rods were attached to each throw. The crankshaft was supported by three main bearings. The steel pistons had concave heads and five rings; three rings were above the wrist pin, and two bronze rings were below. The underside of the piston had cooling fins to help dissipate heat. For each cylinder, a single spark plug was mounted on its Vee side near the pushrod guide. The spark plugs were fired by a battery-powered Heinz coil and communicator (distributor). The engine used splash lubrication and also a Petersen pressure feed oiler.

On each end of the crankshaft was a manganese bronze flywheel. The outer diameter of the flywheel was lined with woven camel hair to provide a friction surface. Covering the flywheel was a chrome steel cone clutch. Shafts and universal joints connected the drive wheels to the clutches and allowed for steering and independent coil spring suspension. Normal gear would lock the flywheel, clutch, and shaft together so that there was no reduction between the engine and drive wheels; for every revolution of the engine, the drive wheels turned one revolution. Normal engine speed was 1,000 to 1,200 rpm. With its 34 in (864 mm) by 4.5 in (114 mm) front tires, the car was capable of 120 mph (193 km/h) at 1,200 rpm. Of course, different size tires could be used to alter the vehicle’s acceleration and top speed. The rear tires were 34 in (864 mm) by 4 in (102 mm).

Christie and Lewis Strang running in the French Grand Prix in 1907. The car was painted white for the race, the engine cowl had been cut back, exhaust valve covers had been added to the top of the cowl, engine exhaust was now piped out of the cowl and into a muffler (of sorts) seen just behind the front wheel, and crankcase breathers had been added to the front of the car. Note the oil leaking from the camshaft and cross shaft housings.

Low and reverse gears were enabled by a cross shaft on the front of the crankcase. As the cross shaft slid laterally, gears on the shaft meshed with teeth cut into the outside of the clutch drums; at the same time, the clutch disengaged from the flywheel, allowing the speed of the drive wheels to be dictated by the speed of the cross shaft. The cross shaft was geared to the crankshaft at a reduced speed.

The car was only fitted with rear brakes, but two sets were employed. One set of rear brakes acted upon the inner surface of the brake drum while the other set acted upon the drum’s outer surface. The inner and outer brakes were controlled by individual foot pedals; however, the pedals were situated so that both could be pressed simultaneously by one foot.

The rear axle was a hollow steel tube and attached to the frame by semi-elliptic leaf springs. The 25 gal (95 L) fuel tank was easily removed so that it could be inspected by the Grand Prix committee. The car used a pressed steel, channel-section frame. It had a 110 in (2.79 m) wheelbase and a 53 in (1.35 m) track (some sources say a 100 in / 2.54 m wheelbase and a 56 in / 1.42 m track). The car weighed around 1,780 lb (807 kg).

This photo was most likely taken soon after the racer returned from Europe (possibly at Morris Park, New York). The cross shaft, mufflers, and crank case breathers have been removed, but the rest of the car is still in its Grand Prix configuration—apparently still wearing white paint from the Grand Prix. Christie is in the driver’s seat. Note the oil still leaking from the front of the crankcase.

Completed in late April, the Christie racer was tested out on the streets of Long Island, New York at 4 AM. Lewis Strang, who was Christie’s ridding mechanic and nephew, accompanied Christie on this first run. Reportedly, the car broke down after about 20 mi (32 km), but the issues were not severe. The car was repaired and underwent further testing and refinement in May. The racer originally had a cowling that covered the entire engine. Due to cooling issues, the front of this cowling was removed to increase airflow through the radiator. This cowling was continually modified throughout the racer’s life.

In June, Christie, Strang, and the V-4 racer left for France. Thirty-eight cars were entered in the French Grand Prix to be run on 2 July 1907. The race consisted of 10 laps on a 77 km (47.8 mi) course laid out near Dieppe in Northern France. Christie’s racer was the lightest and one of the most powerful racers. It was allocated the race designation WC1 (for Walter Christie 1) and the 12th starting position. The Christie Direct Action Motor Car Company had arranged for several locals to assist with the racer. However, upon arriving in France, Christie and Strang discovered that the helpers were nowhere to be found. Christie and Strang spent their time repainting the car in the white and red colors required for United States racers. They then needed to register the racer in France. With all the administrative work completed, Christie and Strang did not have much time to practice and only made one test lap around the course. This session revealed a sticking exhaust valve, but there was no time for repairs.

Barney Oldfield in the 1907 Christie V-4 racer. It is not known when or where this photo was taken, but a new engine cowling has been installed and the cross shaft has been reinstalled.

Christie and Strang started the race at 6:12 AM and had a tire failure less than two miles later; it was not a good start. Repairs were quickly made, but the car was struggling. Christie picked up the pace and ran a lap in 48 min and 49 sec (58.8 mph / 94.6 km/h). However, this was several minutes slower than the leader. Adding to the trouble of the sticking exhaust valve were a jammed clutch and an overheated main bearing. Christie and Strang retired the V-4 racer on the fifth lap.

Upon return to the United States, Christie was ridiculed for his poor showing at the Grand Prix. He responded that he had spent his own money on his effort, and, unlike other American auto manufactures, he “at least did something.” Christie went on to challenge his critics to a race “for any distance and for any amount of money, and at any time, on any road or track anywhere.” No one stepped up to accept his challenge.

Christie and Strang ran the racer at various tracks to prove its capabilities and those of the Christie Direct Action Motor Car Company. In August, Christie ran a 52.2 second mile (69.0 mph / 111.0 km/h) on the dirt track at Morris Park, New York. He then ran a 52 second lap (69.2 mph / 111.4 km/h) in Boston, Massachusetts followed by the same time at St. Paul, Minnesota. On 9 September, Christie and Strang were running at speed on the Brunots Track near Pittsburg, Pennsylvania when they struck a wrecked racer from a previous crash on the track. Christie lost control of the car, and both men were thrown from their racer. Strang was uninjured, but Christie was hospitalized with a broken wrist, a sprained back, a lacerated head, and abdominal injuries.

Ned Blakely sits behind the wheel of the Christie racer at Ormond Beach, Florida in March 1908. Although Christie made a 109 mph (175 km/h) test run, the car did not finishing any official race.

The V-4 racer was repaired, and Christie and Strang took the car to Birmingham, Alabama. Christie was still recovering from his injuries and did not drive much. The next stop was New Orleans, Louisiana, but the meet was delayed. Christie made arrangements to send the car back to New York and returned there himself. However, the car never arrived. Subsequently, Christie discovered that Strang had taken the car back to Birmingham, Alabama were he set a record on 16 October, lapping the mile track in 51.6 seconds (69.8 mph / 112.3 km/h). Strang also ran the V-4 racer at a few other events.

This unauthorized use of his car deeply upset Christie, and it was the end of his association with Strang. Some of Strang’s behavior can be attributed to the negative influence of his and Christie’s manager, William Pickens. To make matters worse, before Christie knew the car was missing, he had sold it to William Gould Brokaw. The arrangement allowed Christie to continue to drive the 1907 V-4 racer so long as he kept it in good repair. When Christie finally tracked down the missing racer and had it returned to his shop in New York, the engine had a cracked cylinder and other damage.

An undated photo illustrating the many changes made to the 1907 V-4 racer. The cross shaft on the front of the crankcase and the engine cowling have been completely removed. A more conventional radiator has been installed along with new exhaust stacks. A much smaller fuel tank (just in front of the radiator) has replaced the original tank. Note the twin front tires on the right drive wheel. Race promoter Ernest Moross is behind the wheel.

Repairs (which included a new crankcase) were made, and Ned Blakely was tasked with racing the car at Ormond Beach, Florida in March 1908. Unfortunately, in a 100 mi (161 km) race on the first day of the event, a valve broke and took the car out of the race. Repairs were completed, but during a 256 mile (412 km) race on the third day, a spark plug broke off and damaged a cylinder, ending the racer’s participation at the event. Sometime during this event, Christie covered a mile in 33 seconds (109.1 mph / 175.5 km/h) on a test run, but it was not officially timed.

The car was again repaired. In early June, Morton J. Seymour was behind the wheel of the racer practicing for an event on Long Island, New York when he crashed and most likely overturned the car. The radiator was destroyed, but Christie managed to repair the car enough to run without cooling water for an attempt on the 1 km (.62 mi) record. Seymour covered the km in 26.6 seconds (84.1 mph / 135.3 km/h)—not fast enough for a new record.

Another view of the modified 1907 racer. The car still has the twin right drive wheels. Christie is in the driver’s seat. Note how the steering column passes through the radiator.

The racer was repaired yet again and further modified. A new (more conventional) radiator was installed. A small fuel tank was installed in front of the radiator, and the large, rear tank was removed. The low and reverse gears and the engine cowling were completely removed. Seymour and Christie went on to drive the car at a few events. After this, Christie and his good friend Barney Oldfield toured the country and made many appearances at various tracks.

At some point, after the new radiator, the V-4 racer had twin front right wheels installed to help the front-wheel drive vehicle on the circle tracks. It is not clear how often the car ran in this configuration. In December 1908, the racer was running at Tanforan Park near San Francisco, California, but a cracked cylinder took it and its driver Hughie Hughes out of competition. In January 1909, Hughes crashed the car at a race in Phoenix, Arizona, and that was the last known event for Christie’s 1907 V-4 racer; the car’s final disposition is not known. By this time, the Christie Direct Action Motor Car Company had fallen into receivership. Undaunted, Christie had established the Walter Christie Automobile Company in September 1908 and went to work on another V-4 racer.

Note: Some sources state that Blakely ran a 35 second mile in the 1907 V-4 racer at “a beach near Atlantic City” prior to March 1908. However, I was unable to find specifics to this event and feel it may have been confused with the 35.2 second run Christie made at Ventnor Beach, which is near Atlantic City, in 1905.

A photo from the 1908 Minnesota State Fair with Christie, DePalma, and Clark. The fair was held in St. Paul from 31 August to 5 September. Note that the Christie racer has only one front right drive wheel.