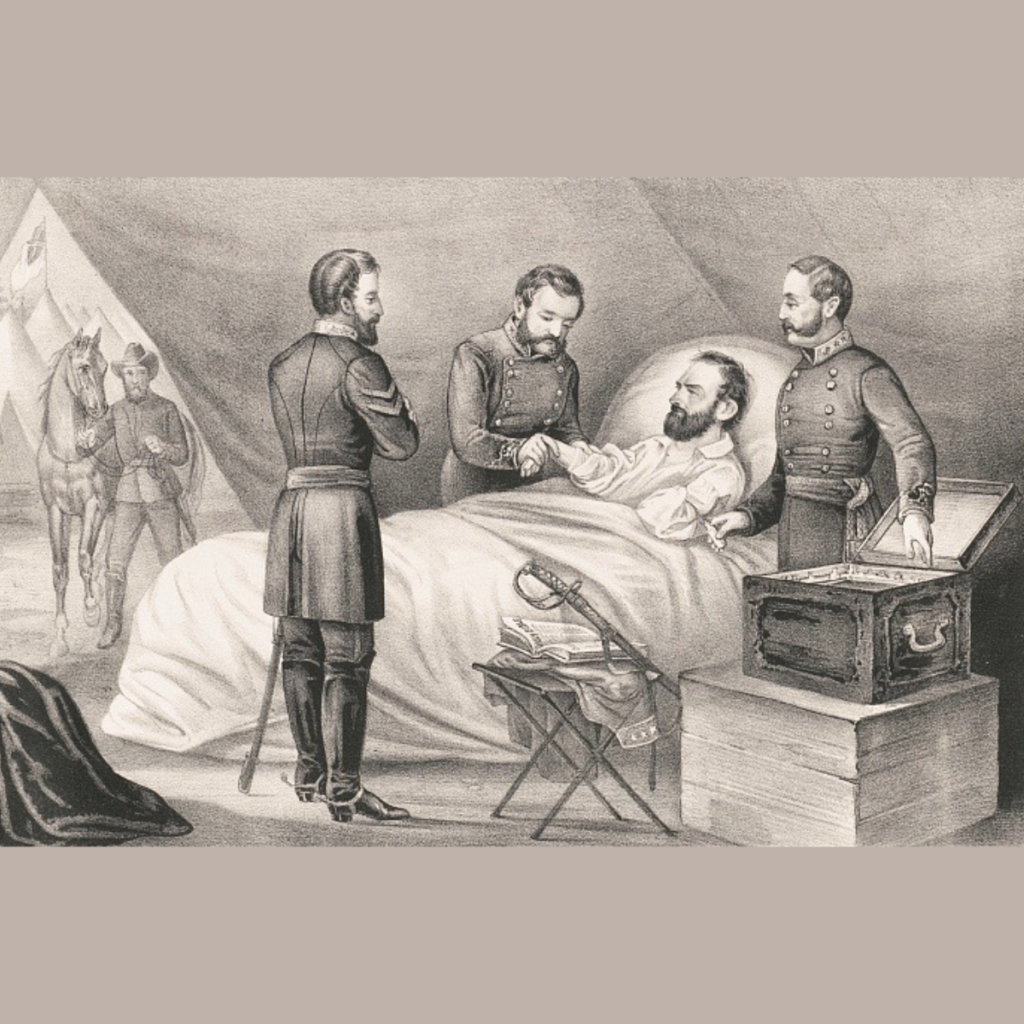

Illustration of Stonewall Jackson’s deathbed. Image credit: Navel from Wikipedia.

General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia fought the Union’s Army of the Potomac, which was commanded by Major General Joseph Hooker, at the Battle of Chancellorsville in Virginia between April 30 and May 6, 1863. The Battle of Chancellorsville is known as one of General Lee’s greatest victories of the American Civil War because, despite being massively outnumbered, Lee forced Hooker’s army to retreat. But General Lee suffered a significant loss during the battle when one of his most brilliant strategists, General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson, was shot and died shortly after.

General “Stonewall” Jackson was shot in his left arm and right hand at the Battle of Chancellorsville on May 2, 1863. Although the bullets were removed and his left arm was amputated immediately, he died eight days later. Investigators studied the projectiles that were removed from Jackson’s body in order to verify who fired the lethal shots. This case is significant because it is one of the earliest applications of ballistic principles in a death investigation.

Thomas Jonathan Jackson (January 21, 1824-May 10, 1863) graduated from West Point in 1846 and fought with the U.S. Army in the Mexican American War. When the American Civil War started in 1861, he trained new recruits for the Confederate Army and was given command of an infantry regiment. “Stonewall” Jackson earned his famous moniker at the First Battle of Bull Run in July of 1861 when the then brigadier general charged his troops forward to reinforce the Confederate defensive line against a Union attack “like a stone wall.” Jackson is probably most famous for his Shenandoah Valley Campaign in the spring of 1862 during which he marched his troops more than 650 miles in order to keep the Union Army from attacking the Confederate capital in Richmond, VA.

From April 30 to May 6, 1863, Jackson fought under the command of General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville. As the fighting started to dwindle at sundown on May 2nd, Jackson and his aids returned to the Confederate lines. As Lee and his men approached, a North Carolina regiment mistook them for Union troops and fired on them. Jackson was hit in his left arm right below the shoulder and in his right hand.1

Dr. Hunter McGuire, the chief surgeon of the Army of Northern Virginia, amputated Stonewall Jackson’s left arm in an attempt to save his life. But Jackson died anyway eight days later on May 10, 1863 and McGuire attributed his death to complications from pneumonia.1

The bullets in Jackson’s left arm and right hand were removed during surgery and were later examined during an investigation into his death to confirm it was the result of friendly fire. It was noteworthy that the projectiles were round balls fired from a smoothbore musket because there were two categories of muskets used during the Civil War, those with smoothbore barrels and those with rifled barrels. 1,2

Image of a 35 remington caliber, microgroove rifled barrel. Image credit: Released into the public domain by Rickochet on Wikipedia.

A smoothbore weapon does not have rifled grooves etched into the barrel. Smoothbore muskets had a shorter range and were less accurate than their rifled counterparts. Rifling, or spiral grooves etched into the walls of the inside of the barrels, was invented in the 16th century but was not part of widespread gun production until the 19th century. This was an important innovation in firearms manufacture because when a bullet passed through the barrel the rifling caused the bullet to spin, which made the shot more stable and accurate. By the time Jackson was shot, most of the muskets used by the Confederate Army were smoothbore and most rifles used by the Union army had rifled barrels.

Ballistic analysis eliminated Union troops as the source of the shot and confirmed witness accounts that Jackson was injured by and eventually killed by his own men.

Most of Stonewall Jackson’s body was sent to his family in Lexington, VA where it was buried. His left arm, however, was buried in a private cemetery at Ellwood Manor, not far from the Chancellorsville battlefield. According to Ramona Martinez in “The Curious Fate Of Stonewall Jackson’s Arm,” Union solders exhumed the limb in 1864 and reburied it in an unknown location. Then in 1903, one of Jackson’s officers erected a granite headstone at what was thought to be the appendage’s final resting place but it’s “unclear” if it marks the exact spot or if it is buried nearby.