John Rhodes Cobb was a fur trader who turned to auto racing and setting endurance records in his Napier-Railton car. The Napier-Railton was designed by Reid Antony Railton, head engineer at Thomson & Taylor. Run by Ken Thomson and Ken Taylor, the company was located at the Brooklands raceway in Surrey, England and specialized in designing and building race cars.

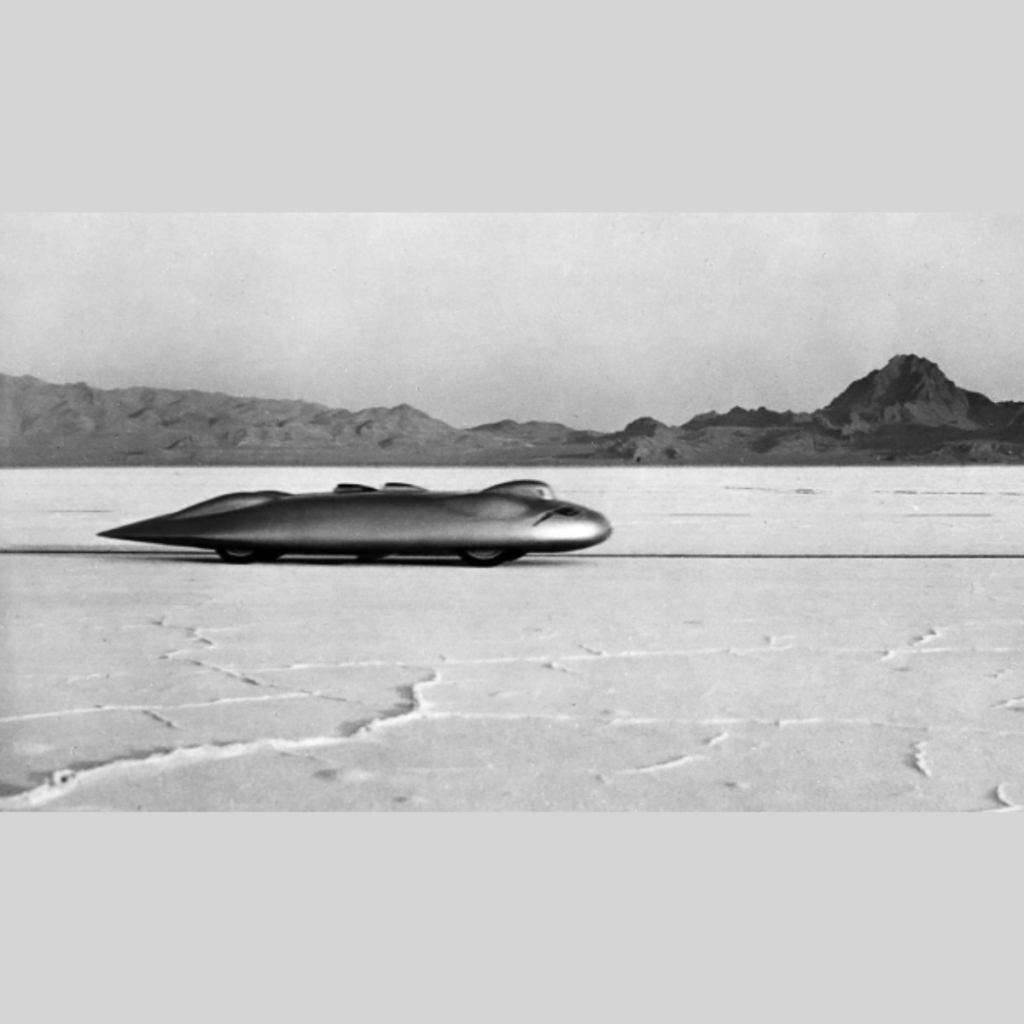

John Cobb and the Railton streak across the Bonneville Salt Flats in 1947. The car was the first to go over 400 mph (644 km/h).

Around October 1935, Cobb approached Railton and Taylor about designing a Land Speed Record (LSR) car. At the time, a new record had just been set on 3 September 1935 by Malcolm Campbell. For the record, Campbell ran his Campbell-Railton-Rolls-Royce Blue Bird car at 301.129 mph (484.620 km/h) on the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah. After the record, Campbell retired from attempting any further LSRs. Railton had done much of the design work on Campbell’s car, and Cobb did not care much for Campbell. What Cobb offered Railton was the freedom to design a LSR car from scratch. All of Railton’s work with Campbell was redesigning and modifying a car that was originally built in 1926.

Cobb made slow, deliberate steps toward his goals, and his work on the LSR car would be no different. It was not until early 1937 that Railton and Ralph Beauchamp began serious design work on the car. At the same time, Cobb’s friend and fellow record-breaker George Eyston began the construction of his own LSR car, Thunderbolt. Eyston’s huge car was powered by two Rolls-Royce R engines and needed eight wheels to distribute its immense weight. While similar in concept and designed to achieve the same goal, Railton’s LSR car design would stand in stark contrast to the Thunderbolt. Railton’s LSR design carried the Thomson & Taylor designation Project Q-5000. Cobb named the car Railton in honor of its designer.

While Cobb was financially well-off, he did not have unlimited funds for an LSR car. Railton wanted to design the car using existing technology and keep its proportions within the limits suitable for four wheels. Railton also felt that four-wheel drive was necessary. Having the front and rear wheels driven independently by their own engine circumvented many challenges and simplified the overall design. The choice to use two Napier Lion W-12 engines was an easy one. Railton had experience with the engine when he first worked on Campbell’s Blue Bird in 1930. The Lion was also selected to power Cobb’s Napier-Railton, and Thomson & Taylor had much experience with the engine type, as they converted them for marine use.

Rear view of the Railton shortly after its completion in 1938. Once the one-piece body was quickly removed, nearly all of the car’s components were accessible. The large water tank is on the left, and the air brake can be seen forward of the rear tires.

Originally designed in 1917, the Lion was a 12-cylinder aircraft engine with three banks of four cylinders. The center bank extended vertically from the crankcase, with the left and right banks angled at 60 degrees from the center bank. Two supercharged Racing Lion VIID engines were available for Cobb’s LSR car. Built in 1929, the engines had been used by Marion Barbara (Joe) Carstairs to power her Estelle IV motorboat. The Lion VIID was the same type of engine Campbell had used to power his Blue Bird in 1931 and 1932. The modified engines produced 1,480 hp (1,104 kW) at 3,600 rpm during tests, but would only produce 1,250 hp (932 kW) at Bonneville’s 4,200-ft (1,280-m) elevation. Carstairs gave both Lion VIID engines to Cobb. Incidentally, Carstairs had funded Campbell’s purchase of two Lion VIID engines in 1930 for his Blue Bird.

After the basic design of the car’s body was determined by wind tunnel tests, Railton focused on filling the body with the needed equipment. The Railton’s frame was a single central boxed girder made from high-strength steel and perforated with large lightening holes. The girder was 11 in (279 mm) wide and varied between 8 and 12 in (203 to 305 mm) tall. When viewed from above, the girder took the shape of a flattened S. Mounted above the front and rear of the girder were the front and rear axles. The cockpit was mounted in front of the front axle on cantilevered supports that extended from the girder. The central part of the girder was angled seven degrees across the car’s centerline. Staggered outriggers extended from each side of the girder to support a Lion engine. The engines were installed 10 degrees off the car’s centerline. The front engine was offset to the right and drove the rear wheels, and the rear engine was offset to the left and drove the front wheels.

Each engine drove a three-speed transmission without a conventional clutch or flywheel. Gear changes were made carefully and with the aid of an overrunning clutch device with locking dogs. Linkages were synchronized so that the single throttle pedal operated both engines, the single clutch pedal unlocked both clutches, and the single gearshift lever operated both transmissions. Each driveshaft also incorporated an 11 in (279 mm) drum brake with hydraulically actuated shoes contracting on its outer diameter. The drums were water-cooled, utilizing the same coolant as the engines. Just forward of the rear wheels was a pneumatic airbrake. Its operation could be linked to the brake pedal so that it deployed vertically as the brake was pressed.

Front view of the Railton on the Salt Flats in 1938. The open covers at the bottom of the car allowed access for two of the body’s eight mounts. Note that the air brake has been removed, as Cobb found the driveshaft brakes more than adequate.

The front axle featured a differential and independent wishbone suspension. The rear axle was narrower than the front and had a solid housing with no differential. The axles’ final drive ratio was 1.35. A combination coil spring and shock absorber controlled the suspension’s movement at each wheel. Forward of the left engine was a 90 US gal (75 Imp gal / 341 L) water tank for engine cooling. The tank was filled with ice, and delivered water to the engines. The Railton had no radiator, and the heated water was purged after passing through the engines. Behind the right engine was a 22 US gal (18 Imp gal / 82 L) fuel tank and an 18 US gal (15 Imp gal / 68 L) oil tank.

The Railton was entirely encased by its streamlined body. The body was designed to not create any lift. Wind tunnel experiments and calculations indicated that the nose of the car would need to be lifted 12 in (305 mm) before aerodynamic lift overcame the car’s weight. The maximum expected lift on the Bonneville Salt Flats was 3 in (76 mm). The one-piece upper body was made of aluminum panels welded and riveted to aluminum supports. The body weighed approximately 450 lb (204 kg) and was designed to be quickly removed to allow access to the entire vehicle for servicing. The 44 x 7.75 in (1,118 x 197 mm) Dunlop tires were mounted on 31 x 7 in (787 x 178 mm) steel wheels and were concealed beneath humps protruding above the body’s upper surface. A square opening covered the cockpit, which was sealed by an aluminum cover with a bulge and a small windscreen for the driver’s head. Two cockpit covers were built, one with an open top and one with a closed top. The open top version was discarded shortly after arriving at Bonneville.

The car’s body could be lowered in place over the seated driver, or the driver could enter the cockpit with the body in place via the opening. However, an overhanging structure to the cockpit opening was needed to support the driver if the body was in place. An undershield covered the underside of the chassis. The body was secured to the car’s frame at eight points and attached to the undershiled via approximately 36 Dzus fasteners. Exhaust from the upper cylinder bank of each engine exited via a manifold protruding above the body. Exhaust from each engine’s left and right cylinder banks exited via a manifold protruding from the underside of the car. The inboard exhaust passed though the girder frame. All exhaust manifolds were directed to the rear. The Railton was 28 ft long (8.53 m), 8 ft (2.44 m) wide, and 4 ft 3 in (1.30 m) tall. The car’s wheelbase was 13 ft 6 in (4.11 m). The front axle had a track of 5 ft 6 in (1.68 m) and the rear track was 3 ft 6 in (1.07 m). The Railton weighed 6,280 lb (2,849 kg).

The Railton being prepared at Bonneville in 1939. The fuel tank has been relocated to the car’s port side, and a large ice tank has been added at the back of the car. The man by the body is painting the Gilmore Red Lion on the nose of the car.

On 5 April 1938, the nearly-complete Railton was debuted for the press. The car was missing its wheel covers, but the craftsmanship involved in its construction and the vehicle’s purpose were evident. Attending the event was Eyston, who, in his Thunderbolt car, had established a new LSR of 311.42 mph (501.18 km/h) over the mile (1.6 km) and 312.20 mph (502.44 km/h) over the km (.6 mi) on 19 November 1937. The Railton was first displayed to the public on 18 April at Brooklands. There were no suitable places in Britain to test the car, so once it was completed, it was packed up and sent to the United States at the end of July.

When Cobb, his team, and the Railton arrived on the Bonneville Salt Flats, Eyston and Thunderbolt had been there for a few weeks. The weather had been bad, and Eyston had not been able to make any record attempts. The course was shortened to about 10 miles (16 km) because of the poor conditions. For starting, first gear was engaged, and the Railton was pushed by a truck to about 20 mph (32 km/h), at which point the magnetos were energized to start the engines. Cobb began testing the Railton, including a first shakedown run up to around 250 mph (402 km/h) without the car’s body. Initial test runs with the body resulted in deformations caused by air pressure pushing on specific areas at the rear of the body. Also, hot exhaust from the center cylinder banks damaged the top of the aluminum body. The body was straightened and reinforced, and an asbestos-lined steel shield was added behind the upper exhaust stacks. On 20 August 1938, conditions had improved, and Cobb took the Railton out for a serious test run. The peak speed was 300 mph (483 km/h) and the Railton averaged 270 mph (435 km/h) over the mile (1.6 km).

On 25 August 1938, the camera timing equipment failed to record Eyston in the Thunderbolt on what would have been a record-breaking run. The failure was caused by a lack of contrast between the car and the background. As a result, both Thunderbolt and Railton were partially painted black to improve contrast. On 27 August, Eyston in the Thunderbolt established a new LSR at 345.49 mph (556.01 km/h) for the mile (1.6 km) and 345.21 mph (555.56 km/h) for the km (.6 mi).

Cobb and the Railton making a run on the Salt Flats in 1939. The trip that year was quite successful, but the start of World War II overshadowed the records.

On 30 August 1938, Cobb made a record attempt. The Railton’s quick acceleration caused the tires to spin, subsequently damaging them, and the attempt was aborted. Even so, Cobb reached 325 mph (523 km/h). More work was done while the surface of the Salt Flats continued to improve. Cobb had found that the driveshaft friction brakes were sufficient to stop the car, and the airbrake was removed. A record attempt was made on 12 September, but issues with shifting the car resulted in a speed of 342.50 mph (551 km/h). With the knowledge and experienced gained by all the previous runs, another record attempt was made on 15 September. Cobb made his run north and covered the mile (1.6 km) at an average of 353.29 mph (568.57 km/h). The body was quickly removed, and the tires were changed during the turnaround. On the return south, the Railton averaged 347.16 mph (558.70 km/h). Cobb and the Railton were successful and set new records of 350.20 mph (356.59 km/h) over the mile (1.6 km) and 350.10 mph (563.43 km/h) over the km (.6 mi).

Eyston and his team had been modifying Thunderbolt for even more speed in case Cobb got the record. On 16 September 1938, one day after Cobb’s record run, Eyston and Thunderbolt made another attempt. The runs established a new LSR at an average of 357.50 mph (575.34 km/h) for the mile (1.6 km) and 357.34 mph (575.08 km/h) for the km (.6 mi).

Cobb and Railton knew their car was capable of more speed. They also learned a lot from its first outing and had a number of modifications in mind. The decision was made to not push the Railton for higher speeds, but to return to England, modify the car, and return to Bonneville in 1939, when conditions might be even better.

Cobb sits in the bodyless Railton in 1947. This image illustrates the tight fit under the body of the two Lion engines, various tanks, and other components. The twin belts, pulley, and shaft of the anti-stalling device can be seen between the cockpit and rear engine, which drove the front wheels.

Back in England, the Railton’s frame was modified to prevent its deflection by engine torque, and the suspension was upgraded. The cooling system was revised by incorporating a new 90 US gal (75 Imp gal / 341 L) tank for ice between and behind the car’s rear wheels. A new 22 US gal (18 Imp gal / 21 L) water tank with an additional header tank of about 6 US gal (5 Imp gal / 23 L) replaced the fuel tank on the right side of the car. The fuel tank was relocated to the left side of the car where the old water tank used to be. For the new cooling system, a thermostat controlled the flow of ice water from the ice tank to the water tank. Water from the water tank flowed to the engines. The total-loss system did not circulate water back to the tank, but vented the heated water out of the car. An opening was added at the front of the car that ducted air to the front engine. The engines’ supercharger gears were changed to increase impeller speed and provide additional boost. The Gilmore Oil Company of California was brought on as a major sponsor for the 1939 record attempt, and the car was often referred to as the Railton Red Lion for that year. Gilmore’s mascot/logo was a red lion, and the company had a line of Red Lion Gasoline.

Cobb, his team, and the Railton were back at the Bonneville Salt Flats in mid-August 1939. The salt was in good condition, and Cobb would have a course of about 13 miles (21 km) for the record attempt. On 17 August, a single run north was made at 352.94 mph (568.00 km/h). A tire tread had separated, and some adjustments to the car were needed. The baffling in the coolant header tank was subsequently modified, and the car was put back into good working order. On 22 August, an attempt was made, and speeds for the run north were recorded at 369.23 mph (594.22 km/h) for the mile (1.6 km) and 365.57 mph (588.33 km/h) for the km (.6 mi). On the return south, the left engine powering the front axle acted up, and the run was aborted. Adjustments were made to the carburetors, and another run was planned for the following day.

On 23 August 1939, the car was prepared, and Cobb set off in the early morning. The run north was covered at 370.75 mph (596.66 km/h) through the mile (1.6 km) and 367.92 mph (592.11 km/h) through the km (.6 mi). The car was back on the course in 25 minutes, after changing all four tires and adding fuel, oil, and water. On the run south, the Railton averaged 366.97 mph (590.85 km/h) over the mile (1.6 km) and 371.59 mph (598.02 km/h) over the km (.6 mi). The average of the runs were new LSRs at 368.86 mph (593.62 km/h) for the mile (1.6 km) and 369.74 mph (595.04 km/h) for the km (.6 mi). Cobb had exceeded six miles a minute, and a tachograph recording unit in the car indicated the peak speed was 380 mph (612 km/h).

While the body could be lifted by six men, many hands make light work. The oil tank is just forward of the rear wheel, followed by the relocated (in 1939) water and header tank. Many Dzus fasteners used to secure the body can be seen on the undershield. Note the very forward position of the driver

The Railton had performed so well that the decision was made to attempt longer distance records, and the car and the course were subsequently reconfigured. On 26 August 1939, Cobb and the Railton set new speed records covering 5 km (3.1 mi) at 326.66 mph (525.71 km/h), 5 miles (8.0 km) at 302.20 mph (486.34 km/h / timing equipment issues made this speed unofficial), 10 km (6.2 mi) at 283.01 mph (455.46 km/h), and 10 miles (16 mi) at 270.35 mph (435.09 km/h). Since the runs were made on the 13-mile (21-km) course, Cobb applied the brakes before exiting the longer, timed sections.

When the team had set off for the United States, Europe was in an unstable state and seemingly headed toward war. On 3 September 1939, as the team returned to England after their successful record runs, Britain declared war on Germany after the latter’s invasion of Poland on 1 September. Against such a backdrop, record setting became insignificant and irrelevant. During the war, the Railton was placed in storage, and Cobb served as a pilot with the Air Transport Auxiliary. But there was still some unfinished business, as Cobb knew the Railton was capable of more speed.

Toward the end of 1945, Cobb had the Railton removed from storage and sent to the Thomson & Taylor shop to be put in working order. Since the engines did not have a flywheel, they had a tendency to rev down and stall out during gear changes. Such an occurrence essentially brought a record run to an end. While the car was being worked on, Railton, who was now living in the United States, had a device fitted to both engines to prevent the stalls. The device was essentially a shaft that connected the engine to its drive line via a belt-driven overrunning clutch. If the engine speed dropped below one-seventh that of the drive line, the shaft turned by the drive line would keep the engine running. Other modifications were additional ducting to feed air from the opening at the front of the body to both engines and changing the final drive gears for high speed. New fuels allowed the engines to operate up to 4,000 rpm, and the pair produced a combined 3,300 hp (2,461 kW). The work on the Railton was performed under the ever-watchful eye of Ken Taylor. The Gilmore Oil Company, a major sponsor from 1939, had been bought out by the Socony-Vacuum Oil Company, which marketed its products under the “Mobil” name. The company agreed to sponsor Cobb’s efforts in 1947, and the car became the Railton Mobil Special.

A serious Cobb peers out the windscreen of the Railton. The slits forward of the canopy brought in air to the cockpit. A steel and asbestos panel behind the upper exhaust stacks protected the car’s body from heat damage.

The restored Railton was displayed before the press in late June 1947 and departed for Bonneville in July. The salt flats and the course were found to be in poor condition, and the Railton’s engines ran roughly. It took some time to resolve carburation issues and make the engines run right. One of the engines was later damaged during a test run. A camshaft was shipped from England to repair the Lion. When the engine issues had been resolved, the ice tank was punctured during a test run. After the tank was repaired, everything was finally in order for a test run on 14 September. The run north was timed at 375.32 mph (604.02 km/h). However, the rough course had caused the aluminum body to crack, necessitating yet more repairs.

On 16 September 1947, the wind had picked up considerably and the course was still less than ideal, but the car was ready. Cobb decided to make a record attempt. Setting off to the south, Cobb shifted into second gear at around 120 mph (193 km/h) and hit third at around 250 mph (402 km/h). The Railton shot through the measured mile (1.6 km) at 385.645 mph (620.635 km/h). The tires were changed and fluids refilled. On the run north, Cobb covered the mile (1.6 km) at 403.136 mph (648.785 km/h). The two-way average of the runs was a new LSR at 394.197 mph (634.399 km/h). And so it was that a 47-year-old man in a 10-year-old car with 20-year-old engines established a new LSR. It had taken quite a bit of effort to set the record in 1947, but Cobb and the team were confident the car could break 400 mph (644 km/h) on both runs if the course were a little better and the wind a little less. The Railton had left the measured mile (1.6 km) at about 410 mph (660 km) and was still accelerating. Plans were started to make another attempt the next day, but a serious rainstorm ended any hope for further runs.

LSRs were big news in the late 1920s and early 1930s. By 1947, and with no challengers on the horizon, Cobb breaking his own record was not nearly as sensational as previous LSRs. Cobb decided not to race the Railton again unless his record was broken. The LSR remained Cobb’s long after his tragic death on 29 September 1952, when his Crusader jet boat disintegrated during a water speed record attempt at over 206 mph (332 km/h). Cobb did make at least one demonstration of the Railton at Silverstone Circuit in England on 20 August 1949. In 1953, the Railton was sold by Cobb’s estate to the Dunlop Rubber Company, which donated it to the Museum of Science and Industry in Birmingham in July 1955. The car was displayed in the United States in 1954 (New York) and 1962 (San Francisco), and at the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958. In September 2001, the Railton was moved to the Thinktank, Birmingham Science Museum, where the car is currently on display.

The Railton on the wide expanses of the Salt Flats in 1947. The various exhaust manifolds can be seen above and below the body. Note the two streams of water pouring out the underside of the car from the total-loss cooling system.

Essentially, Cobb and the Railton held the LSR for 25 years*—from 1939 until Donald Campbell went 403.10 mph (648.73 km/h) in the turboshaft-powered Bluebird CN7 on 17 July 1964. Cobb’s record represented the end of an era, as later speed machines used jet engines to push them along. But, the LSR for the class of piston-powered, wheel-driven cars is still the goal for many racers. On 9 September 1960, Micky Thompson made one run at 406.60 mph (654.36 km/h) in the Challenger 1 before a failed transmission aborted his return. Bob Summers went 409.277 mph (658.667 km/h) in Goldenrod on 12 November 1965, a speed that was not bettered until 21 August 1991, when Al Teague averaged 409.986 mph in Spirit of ’76. Tom Burkland in the Burkland 411 Streamliner achieved 415.896 mph (669.319 km/h) on 26 September 2008. On 17 September 2012, George Poteet in Speed Demon averaged 439.024 mph (706.541 km/h) over the mile (1.6 km). In a car originally built by his father in 1968, Danny Thompson averaged 448.757 mph (722.204 km/h) in Challenger 2 on 12 August 2018. On 13 August 2020, Poteet in Speed Demon took back the record, averaging 470.016 mph (756.417 km/h) over the mile (1.6 km).

*Or 24 years if Craig Breedlove’s 407.447 mph (655.722 km/h) run in Spirit of America on 5 August 1963 is considered. At the time, the record for the three-wheel, jet-powered, non-wheel-driven Spirit of America was not officially recognized.

Note: Spirit of ’76 and Burkland 411 Streamliner both used supercharged engines, while Goldenrod was normally aspirated. Goldenrod’s speed record for a piston-powered, normally aspirated, wheel-driven car stood for 45 years until 21 September 2010, when Charles Nearburg in Spirit of Rett achieved 414.316 mph (666.777 km/h).

The Railton on display at the Thinktank, Birmingham Science Museum. Although fitting, the name “Dunlop” was never painted on the car while it was breaking records. (Geni image via Wikimedia Commons)