Using the way computers function as a source for analogy, a new study has discovered common patterns of social and cultural organization that unite hunter-gatherer cultures around the world and through time.

In this research project, the social structures of many modern hunter-gatherer groups were compared and contrasted. Certain universal patterns of organization were found, of a type that are familiar to computer scientists who study what are referred to as “small-world” network configurations. This type of network maximizes the efficiency of energy, and information flows within a relatively small physical space, producing an impressive collective computing power that can be used to solve complex problems of all types.

The idea to apply a computer science concept to the study of hunter-gatherer cultures was the brainchild of University of Texas-San Antonio anthropologist Marcus Hamilton, who has just published the results of his analysis in the Journal of Social Computing. Professor Hamilton’s work provides a convincing framework for interpretation that explains why the hunter-gatherer model has worked so well for so much of human history, for groups that lived 300,000 years ago and for the few hunter-gatherer societies that managed to survive the rise of modern industrial civilization.

Modern hunter-gatherer group in Namibia. (hecke71 / Adobe Stock)

Small-World Networks are the Answer

On the intelligence scale, several humans working together can outperform an individual. The interactions within the group function as a form of collective computation, which can produce a more comprehensive understanding of the world and more effective solutions to problems.

However, the energy required to take full advantage of the power of collective computation is not insignificant. A large group of people occupying a particular area will all need to be fed, housed, clothed, and otherwise provided for, ultimately through the harvest and consumption of available natural resources. If population is not controlled the group can become too large to function efficiently, meaning that there aren’t enough resources available to take care of everyone’s needs adequately.

According to Marcus Hamilton, hunter-gatherer societies chose their sizes and developed their characteristic social structures based on the need to optimize energy and information flow, without compromising the capacity of the earth to provide for everyone.

“Up to now, human behavioral ecologists have developed useful mechanistic theories describing [how] energy and information flow is optimized at a local scale, looking at things like foraging behavior, social learning, parental investment, and the amount of time spent at any one location,” Hamilton explained to Tsinghua University Press in Beijing, which joined the Journal of Social Computing in publishing his study. “But there has not been much analysis of the optimization of such flows at the much broader, structural level.”

For the purposes of his research project, Professor Hamilton studied an extensive anthropological database that offered detailed information about 339 hunter-gatherer societies. This database included data on population density, territory size, and group size for different levels of social organization.

This research revealed continuities of scale and structure that united the various hunter-gatherer societies, across multiple levels of organization (i.e., family, band, etc.). Anthropologists over the past two or three centuries have studied the hunter-gatherer lifestyle in forest, tropical, desert, coastal, and tundra environments, and as Professor Hamilton discovered, the same social structures developed over and over again in every environmental context.

These structures could best be defined, Hamilton concluded, as “small-world” networks.

Small-world networks feature clusters of interconnected nodes that are never more than five or six nodes away from other nodes, if you follow the proper pathway.

In computers, such networks are ideal for performing specialized tasks (in local clusters), but also allow for efficient passage of information across the entire network. They can scale up or down in activity level quite efficiently, because they are optimized for information and energy flow.

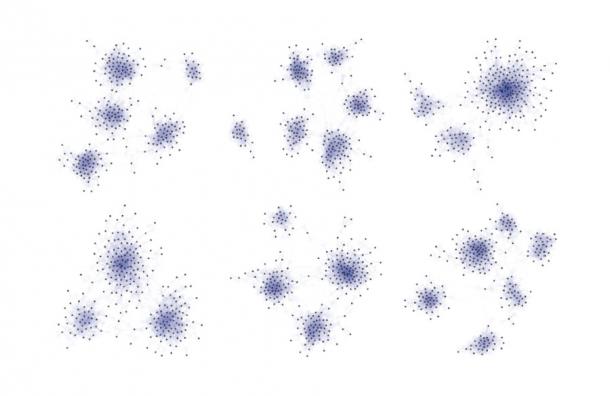

Network structure of six simulated hunter-gatherer metapopulations visualized as hierarchical modular networks. (M. Hamilton / Journal of Social Computing)

In human terms, this is equivalent to a relatively small group that is tightly interconnected that a common purpose can be preserved and everyone’s capacity to contribute can be fully exploited. The group remains small but not too small, allowing for an impressive collective intelligence overall.

“An ever-larger band size should deliver ever increasing amounts of better understanding of the world, and thus superior fitness,” Hamilton noted. “But this increases the chances of ‘free riders’ who benefit from the collective computation but contribute little to it.”

With smaller groups this problem is eliminated, since social pressures to conform and contribute are easier to maintain when everyone knows everyone else and knows what they’re doing or not doing. Fewer people does mean fewer minds are available to contribute to collective problem-solving. But the great interconnectivity of the small-world social network ensures that everyone’s good ideas will be heard and considered by all, and that any valuable information they have to share will be passed on quickly so that everyone else has access to it up and down the line.

The Delicate Balance of the Ancient Hunter-Gatherers

Because of its structural and theoretical nature, this new research can apply equally well to modern and prehistoric hunter-gatherer societies.

Land to occupy, animals to hunt or fish for, firewood to burn, and water to drink were all plentiful in prehistoric times. Presumably, larger-than-normal hunter-gatherer groups could have survived 50,000 or even 300,000 years ago without worrying about running out of resources. They could have moved from place to place into empty lands without worrying about infringing on others’ territories, likely finding significant sources of nourishment wherever they went. The total number of humans living on Earth probably didn’t surpass the one million mark until around 12,000 years ago or so, meaning prehistoric hunter-gatherers lived in a world that was barely populated at all in comparison to our modern frame of reference.

And yet, despite low population density and plentiful resources, ancient hunter-gatherer society populations remained small. This new research shows why this would have been, as the efficiency gains enjoyed of the small-world network model would have been available at any time and place.

The needs of the people living in smaller and more cohesive groups could always be more easily met, even where resources were usually available in abundance. The free rider problem would have been an issue then as now, and even hunter-gatherers organizing 200,000 years ago would have seen the advantages of eliminating that possibility.

Only with the domestication of plants and animals and the invention of agriculture approximately 12,000 years ago did another viable option for organizing human society emerge. Intensive crop production on relatively small plots of land allowed for greater population densities, without leading to unsustainable resource exploitation. It was therefore possible to exploit the advantages of the increased collective brainpower offered by larger populations, without worrying as much about possible land or food shortages.

In the future, Professor Hamilton hopes to extend his analysis to study how issues of energy and information flow have impacted societal development in all its forms, across all human time. If successful he may add new and interesting details to the study of how settled villages, cities and nation-states came to replace hunter-gatherer groups as the dominant forms of social organization in historic times.

Top image: Representation of a prehistoric hunter-gatherer group. Source: Gorodenkoff / Adobe Stock

By Nathan Falde