Louis Delâge was born in Cognac, France on 22 March 1874. He received an engineering degree in 1893 and started a career in the fledgling automobile industry in 1900. In 1903, Delâge joined the Société Renault Frères (Renault Brothers Company). By 1905, Delâge had a good sense of the incredible potential offered by the automotive industry and formed his own automobile company, la Société des Automobiles Delage (the Delage Automobile Company), in Levallois-Perret, just northwest of Paris.

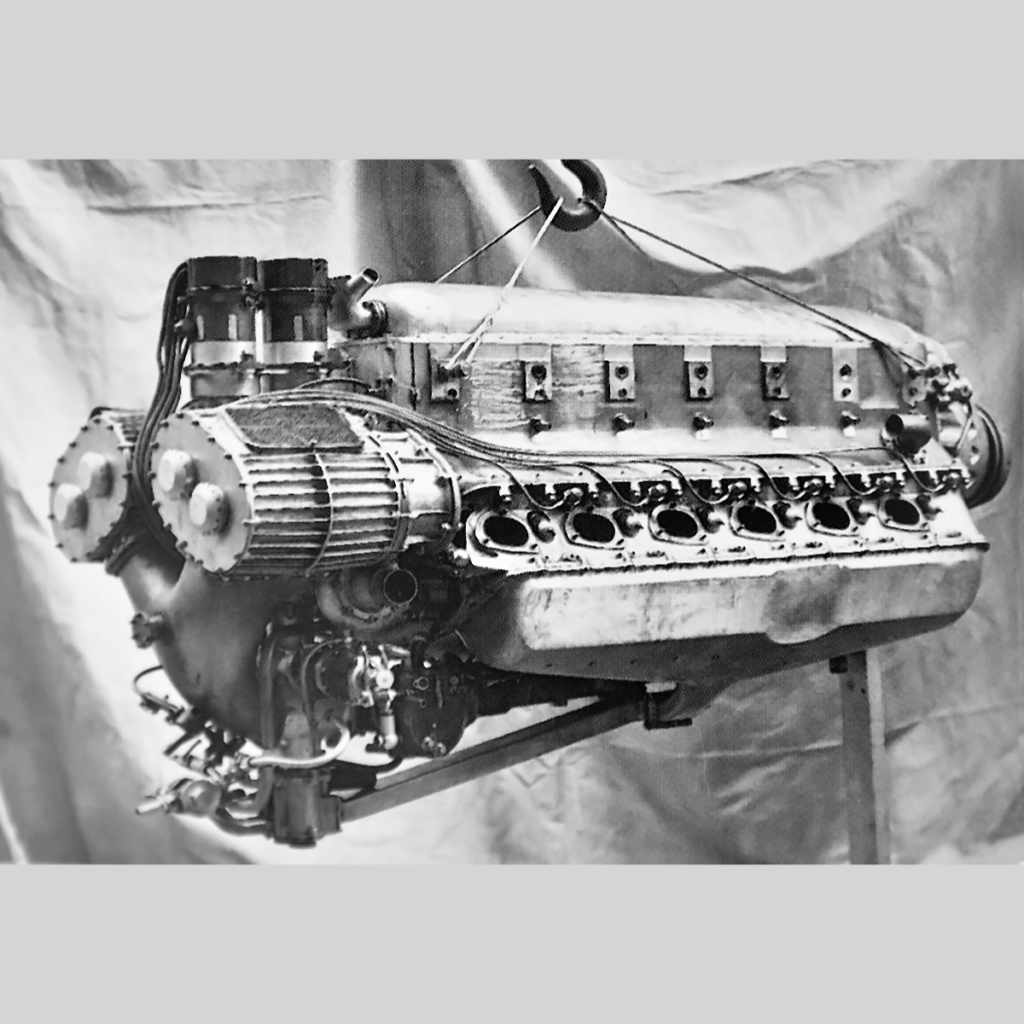

The Delage 12 GVis seen with its Elektron crankcase side covers removed, revealing the magneto and generator. The engine is equipped with double helical propeller reduction gears. The lower engine support can be seen extending from the valve covers to the rear mount.

The Delage automobile was a success, and the company soon also began developing race cars. Delage racers won the 1908 Grand Prix de Dieppe, the 1911 Grand Prix de Boulogne-sur-Mer, the 1913 Grand Prix de France, and the 1914 Indianapolis 500. Racing and the production of passenger cars was halted during World War I, and Delage produced munitions and vehicles for the military. After World War I, Delage returned to the automotive business and began to produce luxury vehicles. In 1921, Albert Lory was hired as a designer, and he was put in charge of the competition department in 1923. That same year, Delage returned to racing. Lory designed the Delage 15S8 Grand Prix racer and its high-revving, straight-eight engine that won the Manufacturers’ Championship in 1927. The company withdrew from competition after this victory.

In 1930, Louis Delâge believed that the lessons learned through the development of the company’s compact and powerful automotive racing engines could be applied to aircraft engines. Lory was tasked with the development of two aircraft engines—the 12 GVis for fighter aircraft and the 12 CDirs for a Coupe Deutsch de la Meurthe racer. The two engines had similar layouts overall and mainly differed in their size. While there were no real restrictions on the fighter engine, the engine for the Coupe Deutsch de la Meurthe race had to be under 488 cu in (8.0 L).

The 12 GVis crankcase as it would be installed with the crankshaft at top: A) gear reduction mounting flange, B) camshaft housing, C) crankshaft mount, D) one of the four bolts extending through the crankcase, E) magneto mount, F) generator mount, G) studs for mounting the cylinder head, H) barely visible hole to receive a cylinder barrel, and I) pass through holes for the valve train’s pushrods.

The 12 GVis and 12 CDirs were water-cooled, inverted V-12 engines equipped with twin superchargers. The engines and their accessories were designed as a compact package with minimal frontal area to encourage better streamlining. Each engine consisted of a cast aluminum crankcase that also formed the lower part of the two cylinder banks, which had an included angle of 60 degrees. As later described, the two engines did have different styles of crankcase designs. Nitrided steel cylinder barrels were bolted via flanges to the two cast aluminum cylinder heads, which were then secured via studs to the crankcase. The cylinder barrels for each bank passed through a large, open water jacket space in the crankcase and were received by openings near the crankshaft. The balanced, one-piece crankshaft spun in roller bearings and was secured to the crankcase by seven main bearings. The crankcase was closed by an Elektron (magnesium alloy) cover. Side-by-side connecting rods with roller bearings were mounted to the crankshaft.

Each cylinder had two spark plugs, two paired intake valves, and two paired exhaust valves. The paired valves for all cylinders were actuated via rockers and pushrods from the engine’s single camshaft located in the Vee between the cylinder banks. A valve spring did not surround each of the valve stems. The spring for each valve pair was mounted adjacent to the valves and applied pressure to the valve pair via a levered arm. As the pushrod acted on the rocker to open the valve pair, the tip of the lever moved down with the valve stems. The opposite end of the lever moved up, further compressing the spring in its mount. The spring exerted tension on the lever to return and hold the valves in the closed position. Delage believed this system reduced the amplitude of the spring’s oscillations, increased the spring’s damping, and allowed for higher engine rpm. A valve rig was reportedly tested to the equivalent of 10,000 engine rpm, which means each valve had 5,000 actuations per minute.

Left, front view of the 12 GVis illustrating the engine compact structure. The barometric valve can be seen on the intake manifold between the cylinder banks. Right, rear view of the 12 GVis displaying the engine’s twin Roots-type supercharger. Note how the rear of the engine bolts to the mount.

Two Roots-type superchargers were mounted to the rear of the engine. These were of a similar design to the superchargers used on Delage automobiles. The superchargers were driven without clutches and directly from the engine at 1.67 (1.5 in some sources) times crankshaft speed. Via twin two-lobe rotors, the superchargers supplied 17.66 cu ft (500 L) of air per second to the intake manifold positioned in the Vee of the engine. The superchargers provided 14.5 psi (1.00 bar) of boost and enabled the engine to maintain its rated power up to 16,404 ft (5,000 m), at which altitude a barometrically-controlled bypass valve was fully closed. This valve prevented over boosting at lower altitudes and sustained a constant intake manifold pressure. The engine’s single carburetor was installed at the Y junction where the two superchargers fed into the intake manifold.

Some sources indicate that the French government ordered a single prototype of the 12 GVis and a single prototype of the 12 CDirs. However, other sources state that no orders for the 12 GVis were ultimately placed, and only a single order for the 12 CDirs was received. Both engines were proposed to power aircraft manufactured by Avions Kellner-Béchereau.

The 12 GVis as displayed at the 1932 Salon de l’Aéronautique. The engine and cowling represented a complete installation package that could be quickly attached to an aircraft. The access panels covering the magento and generator are removed. Note the valve cover protruding from the cowling and the oil cooler mounted above the engine.

The designation of the Delage 12 GVis stood for 12 cylinders, Grand Vitesse (High Speed), inverse (inverted), and suralimenté (supercharged). The engine had a 4.33 in (110 mm) bore and a 4.13 in (105 mm) stroke. Each cylinder displaced 61 cu in (1.0 L), and the engine’s total displacement was 731 cu in (11.97 L). The 12 GVis had a compression ratio of 5.5 (5.8 in some sources) to 1 and initially produced 450 hp (336 kW) at 3,600 rpm. It was believed that the engine’s output could be increased to 550 hp (410 kW) or even 600 hp (447 kW) with further development. The engine weighed 1,014 lb (460 kg). Two propeller gear reductions were offered: a .472 reduction via double helical gears, which was installed on the prototype, and a .528 reduction via Farman-type planetary bevel gears. The propeller turned counterclockwise.

The crankcase of the 12 GVis was cast with compartments on its sides to mount various accessories. A magneto was mounted in the compartment on each side of the engine, and a generator was mounted in the left-side compartment. The compartments were sealed with Elektron covers. The basic form of the engine and its crankcase created an aerodynamic installation that did not need to be covered by a cowling. The back of the 12 GVis was mounted directly to the airframe, and a conventional engine mount was not used. Four long bolts passed through the entire length of the crankcase to secure the engine to its mount. An additional lower support ran from the engine’s Vee to the rear mount. This support bolted to special pads on the inner sides of the valve covers. The engine was further secured by other mounting pads on its rear side.

The Delage 12 CDirs was a direct development from the larger 12 GVis. The engine had a more conventional crankcase without compartments for accessories. The large pipe on the crankcase was the outlet for the cooling water, and another outlet was present on the opposite side.

The 12 GVis was proposed for the Kellner-Béchereau KB-29 fighter, which was based on the KB-28 racer (see below). The 12 GVis was displayed in November 1932 at the Paris Salon de l’Aéronautique. The engine had a cowling covering its lower half, but the upper sides were uncowled, and the crankcase accessory covers were removed. A surface oil cooler was incorporated in a cowing panel mounted above the engine. The 12 GVis may have suffered from reliability issues and failed to complete an acceptance test. Ultimately, the KB-29 fighter was never built, and there were no other known applications for the 12 GVis.

The designation of the Delage 12 CDirs stood for 12 cylinders, Coupe Deutsch, inverse (inverted), réducteur (gear reduction), and suralimenté (supercharged). The engine had a 3.94 in (100 mm) bore and a 3.32 in (84.4 mm) stroke (some sources state 84.5 or 84 mm stroke). Each cylinder displaced 40 cu in (.66 L), and the engine’s total displacement was 485 cu in (7.95 L). The 12 CDirs had a compression ratio of 5.5 (5.2 in some sources) to 1 and initially produced 370 hp (276 kW) at 3,800 rpm. Development of the engine had increased its output to 420 hp (313 kW) at 4,000 rpm, and it was hoped that 450 hp (336 kW) would ultimately be achieved. The engine weighed 816 lb (370 kg). A .487 propeller gear reduction was achieved via double helical gears, and the propeller turned counterclockwise. While still somewhat aerodynamic, the 12 CDirs possessed a conventional crankcase and did not have the compartments that were incorporated into the 12 GVis. Accessories, including two vertical magnetos, were mounted to the rear of the engine. Engine mounting pads were positioned along each side of the crankcase, and the lower support and rear mounts similar to those used on the 12 GVis were employed.

Rear view of the 12 CDirs displaying the two vertical magnetos, two Roots-type superchargers, and the Y intake pipe. The right water pump can be seen under the supercharger. Note the brace extending from the valve covers to the rear of the engine.

The 12 CDirs passed an acceptance test running 53 hours at 4,000 rpm with no reported issues. The engine was installed in the Kellner-Béchereau KB-28 (also known as 28VD) Coupe Deutsch de la Meurthe racer. The aircraft incorporated a surface oil cooler in the front upper cowling, and surface radiators covered the wings. Flown by Maurice Vernhol, the 28VD made its first flight on 12 May 1933. The aircraft needed to qualify for the Coupe Deutsch de la Meurthe by 14 May, so there was little time for development of the airframe or engine. Based on previous tests, Vernhol felt that the ground-adjustable propeller was not utilizing the engine’s full power and requested that it be set to a finer pitch.

In the afternoon on 14 May 1933, Vernhol took off for a qualification flight. As he went to full throttle during his flight, the engine revved to an excess of 4,400 rpm—600 rpm over its intended limit. A coolant hose blew, and Vernhol was sprayed with steam and hot water. Partially blinded, Vernhol attempted an emergency landing, but misjudged the touchdown and hit the ground hard. The landing gear was sheared off, and the aircraft flipped upside down. The engine was torn free, and the fuselage broke behind the cockpit. Vernhol escaped with only minor injuries, but the 28VD was damaged beyond repair. No other aircraft are known to have flown with Delage engines.

Creating powerful and reliable aircraft engines that ran for long periods at high power proved to be more of a challenge than originally anticipated, and Delage abandoned its work on the type in 1934. The company was in a bad financial state and went into bankruptcy in April 1935. That same year, the Delage name and assets were purchased by the Delahaye automobile company.

The Kellner-Béchereau 28VD (KB-28) seen perhaps right before what may have been its last flight. The 28VD was the only aircraft to fly with a Delage engine. Capitaine Maurice Vernhol sits low in the cockpit, illustrating the aircraft’s limited forward visibility. Jacques Kellner is at left, standing next to Louis Delâge. Albert Lory can be seen on the other side of the cockpit. Kellner joined the French Resistance during World War II and was executed by the Nazis on 21 March 1942. Delâge’s automotive company was a victim of the Great Depression and was sold off in April 1935. He died nearly destitute in 1947. Lory went on to design the SNCM 130 and 137 aircraft engines and then worked for Renault after the war.