This week in 1945, Soviet fighter pilot Lt. Mikhail Petrovich Devyatayev made one of military history’s most daring escapes—stealing a Luftwaffe Heinkel 111 bomber and literally flying out of the grasp of his German captors, and taking nine fellow POWs with him.

Devyatayev was a tough trooper who also possessed a flair for shrewdness and daring. A fighter pilot by vocation, he graduated from the Chkalov Military Aviation School of pilots in 1940 and went on to complete 180 combat flights, counting a Junkers Ju-87 and a Focke-Wulf 190 among his kills.

Devyatayev’s luck in the air ran out in the summer of 1944 as he tangled with the Luftwaffe over Ukraine. Then serving as a flight commander in the 104th Guards Fighter Regiment, Devyatayev was piloting an American-built Bell P-39 Airacobra as wingman for his regimental commander when his plane was shot down near Lviv. Injured, Devyatayev landed by parachute on German territory and fell immediately into Nazi hands.

As a Russian military officer, Devyatayev did not expect to live long. The Germans had literally made it official policy to exterminate Russians—either murdering them on sight, or killing them through starvation and forced labor. The strong and sturdy Devyatayev, then 27, soon found himself trapped in the brutal concentration camp system. He attempted an unsuccessful escape from a camp in Lodz, Poland, only to be packed off to the inferno of Sachsenhausen.

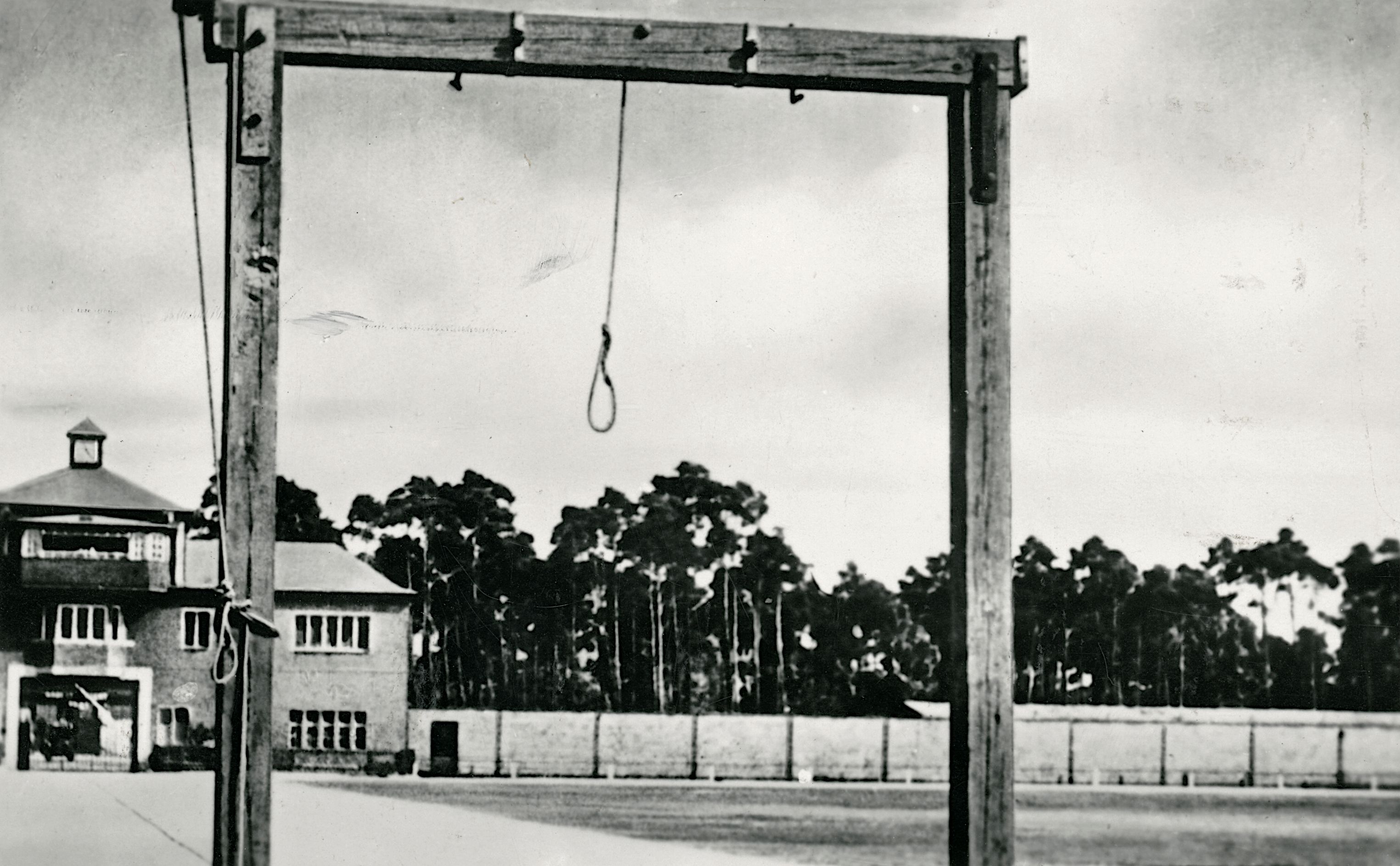

“When we came through the front entrance, two corpses were hanging on it [the gallows],” he later recalled of Sachsenhausen at age 85. “It shocked me. I thought, ‘What place have I come to?’”

After arriving at Sachsenhausen, Devyatayev became aware that his Soviet military service would attract undue attention from German torturers at the camp and thus spell his doom. He managed to swap identities with a dead Soviet infantryman, allegedly using the alias “Nikitenko,” and passing himself off as an ordinary conscript.

Life seemed to get worse for Devyatayev when he was packed into a cattle car in late 1944 and shipped by rail to an unknown location withsome 500 other POWs. He witnessed about 30 men die around him in the railway car during the trip. However, the journey would eventually provide him with a means to escape.

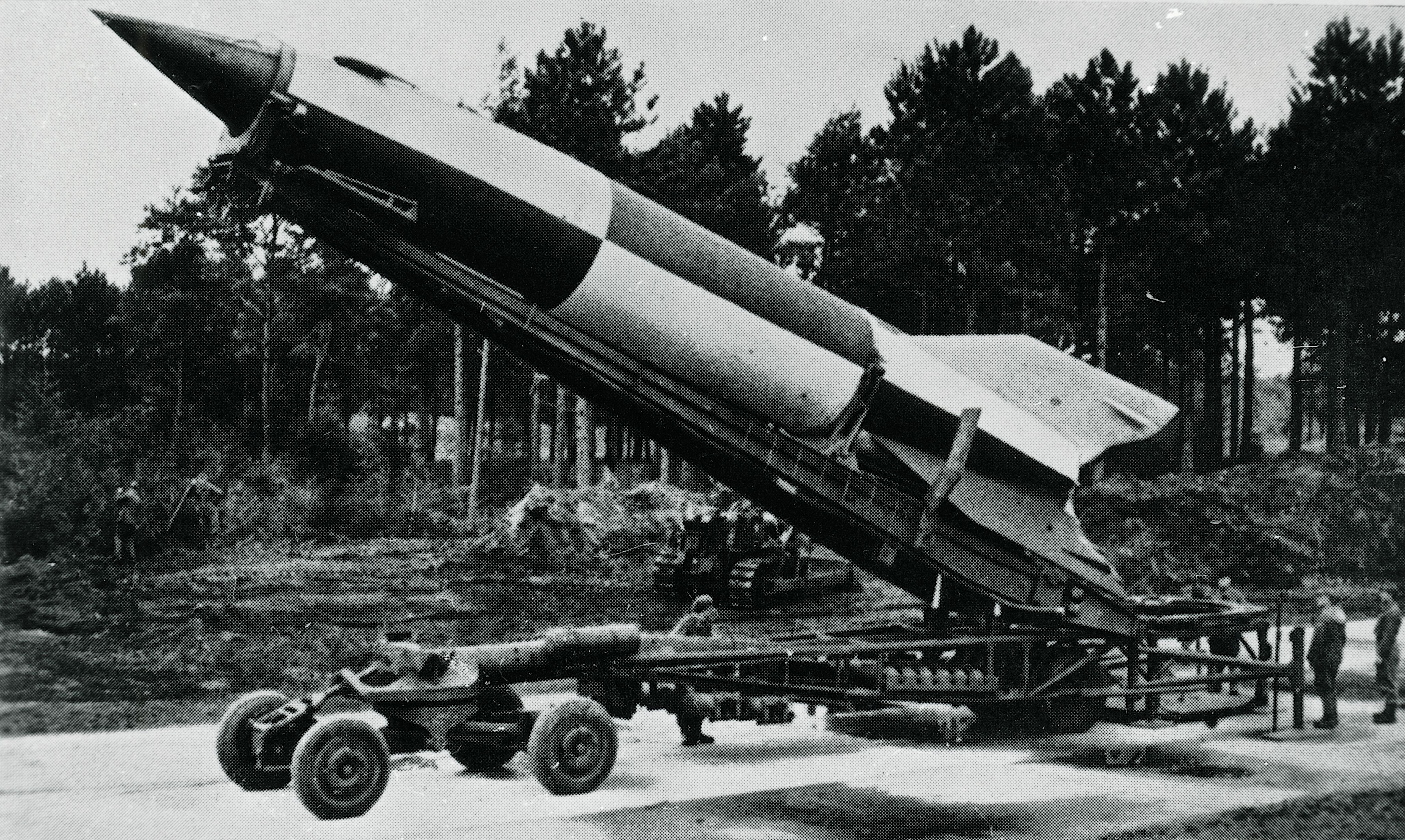

The new site was the town of Peenemünde on the island of Usedom in the Baltic Sea, which today is a tourist destination known for its sunny beaches. Usedom was a Luftwaffe testing site used for the assembly and development of the V-1 and V-2 rockets. Wernher von Braun worked at the rocket development center there.

As the Third Reich began to crumble, the Nazis became more desperate to deploy rocket “wonder weapons.” The High Command’s suicidal stubbornness resulted in more German troops being killed on the frontlines and drew more civilians into the war. Manpower shortages began to take a heavier toll. SS leader Heinrich Himmler opted to keep V-2 rocket production going at full speed through slave labor. A concentration camp at Peenemünde was built for that purpose. Thousands of inmates had been forced to work at the camp, called Karlshagen, since 1943, and continued to be used as slave labor there until the end of the war despite a massive attack by British RAF bombers in August 1943.

For Devyatayev and fellow prisoners, the sunny island was a blazing hell of gruesome working conditions, sadistic guards and endless industrial work. The inmates were forced to assemble explosive devices that would be used to destroy their own people and homelands. They were also forced to clear unexploded ordnance and build runways. They were starved and tortured by SS guards. The physical and emotional distress suffered by inmates was indescribable.

“You could be made into a cripple there,” recalled Devyatayev. “They beat us while we were working. There were ‘unwritten rules.’ One punishment was called ‘Ten Days of Life.’ It meant that a prisoner was beaten for 10 days solid, mornings, afternoons and evenings. If he didn’t die on his own during this time, they would kill him on the tenth day.”

Devyatayev made up his mind that he would escape or die trying. He began to formulate plans to steal a German plane. He had access to a runway and confidence in his skills as a pilot. He began secretly studying the Heinkel 111.

Over a period of time, Devyatayev examined spare parts and pieces of wreckage from the Heinkel 111. Conveniently, the Germans had marked different elements of the aircraft with signs and labels. Devyatayev could not read German but stole the pieces and studied them with other inmates who had better knowledge.

Devyatayev also managed to observe a Heinkel 111 pilot preparing for takeoff. “When the engines roared, I wanted to look with at least one eye at the actions of the pilot who started the engines for heating,” he later wrote in an autobiographical book, “Escape from Hell.”

The German pilot noticed the emaciated prisoner peeking as he wielded the levers—and, apparently wanting to show off, gave a repeat performance.

Despite having only seen this demonstration once, Devyatayev decided he was ready to escape as soon as opportunity presented itself. Working together with a group of five other Russian-speaking inmates, he decided to fly to freedom as soon as the predictably punctual German guards went to lunch.

After calling off two attempts due to the lingering presence of guards on the airfield, the daring band of Russians improvised. On their third attempt, they ambushed and stealthily killed a German trooper using a sharpened crowbar and stole his uniform. In an audacious display of theatrics, one POW put the uniform on and pretended to march the prisoners onto the airfield. Germans observing the area from a distance didn’t immediately detect something was amiss.

A Heinkel 111 was ripe for the taking. Devyatayev quickly bypassed the locked cockpit by breaking a small hole in the casing and prying open the door handle.

Meanwhile a fellow escapee noticed another group of Russian-speaking forced laborers working nearby and invited them to join the escape. Thus a grand total of 10 men came barreling onto the plane, ready to leave or die.

Devyatayev wasn’t exactly sure what he was doing. “I pressed all the buttons at once. The devices did not light up…there were no batteries!” he later wrote, recalling his despair. Thankfully one fellow Russian escapee managed to dash outside, retrieve a cart with batteries and help get the engines started.

Yet Devyatayev’s problems were not over. For all his dash and ingenuity, he had no experience flying a Heinkel 111. As the plane rolled forward, Devyatayev tried to accelerate the engine and slam pedals to achieve takeoff. This sent the plane spinning around the tarmac in a screeching whirl. “As if in a tornado, the plane acquired a furious rotational motion,” he recalled.

By now, the Germans had noticed a problem. They endeavored to stop Devyatayev but narrowly escaped being run over by him as he jerked the plane into position and sped down the runway for takeoff—twice, as the first attempt to achieve liftoff was unsuccessful. It took Devyatayev and two helpers to drag the plane skyward in what must have been a chaotic scene in the cockpit.

After takeoff, the plane spiraled in the air for some time before the daring pilot gained total control of the aircraft. During this time, with wild audacity rivaling the fictional Star Wars hero Han Solo, Devyatayev evaded enemy fire and escaped being shot down by fighter planes, including a Junkers Ju 88, deployed to take him down.

Despite being targeted by Soviet guns, Devyatayev and his friends managed to make a safe landing in friendly territory and return home. Instead of being welcomed as heroes, the men were subjected to suspicion and interrogation by NKVD agents, who were inclined to disbelieve their story and assumed they had cooperated with the Germans. Despite this Devyatayev was able to provide the Soviet authorities with valuable information about Germany’s secret V-2 weapons program, which worked in his favor.

After living ignominiously as a presumed “traitor” for years, Devyatayev was recognized as a Hero of the Soviet Union in 1957. He later visited the site of the Peenemünde facility and met with Germans who had witnessed his spectacular flight, including Günter Hobohm, the Junkers Ju 88 pilot who had been ordered to shoot him down. Devyatayev passed away in 2002.

His son, Alexander Devyatayev, said his father was “driven by the belief that a human being is capable of doing things which should ordinarily be impossible.” MH