First scampering onto the scene around 230 million years ago, theropod dinosaurs were some of the biggest predators on the block — and also some of the smallest. From the ferocious 14,500-pound Tyrannosaurus to the feathery 2-pound Microraptor, these prehistoric beasts pushed size to the extremes.

For decades, paleontologists thought the theropods evolved into giants and pipsqueaks by adjusting the pace of their growth: Only by growing more quickly than their ancestors did they bulk up, and only by growing more slowly did they trim down. But in 2023, an analysis of bones from 42 separate species of theropod put that theory to the test. Published in Science in February, the results revealed that the theropods used an assortment of developmental mechanisms to size up and size down.

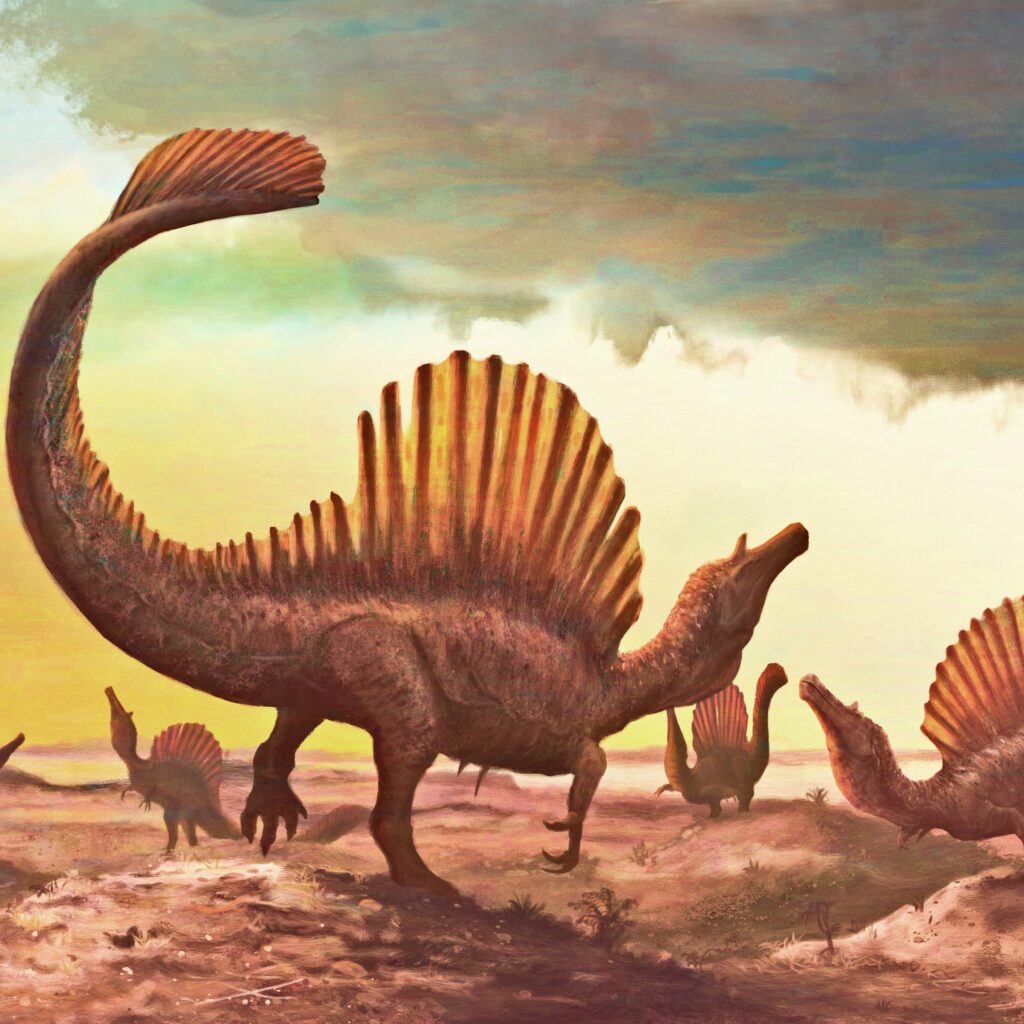

To understand the diverse statures of these predators, the researchers took a microscopic approach. Michael D’Emic, paleontologist at Adelphi University in New York, and colleagues examined sliced, paper-thin sections of more than 80 fossilized bones belonging to species that ranged from the pigeon-sized Mei to the yacht-sized Spinosaurus. They then stuck these cross sections under a powerful microscope to analyze their features.

Like tree trunks, the cross sections contained annual growth rings, which were deposited as the dinosaurs developed. These minuscule rings allowed the researchers to determine the age and rate of growth of the different theropods, with wide rings indicating an accelerated growth rate and narrow rings indicating a decelerated growth rate.

A case-by-case basis

Over the course of a decade, the researchers measured around 500 of these rings, revealing a range of approaches for adding and dropping bulk. Mapping these approaches out on an evolutionary tree, they then gauged the theropods’ growth across the entire fossil family.

“Pound for pound their growth rates were all over the place,” D’Emic says. “We have to basically look at each species or lineage on a case-by-case basis to figure out how they grew.”

Roughly 60 percent of theropod lineages, including tyrannosaurs and allosaurs, became bigger over evolutionary time. But their transformations into apex predators did not occur in only one way. Instead, these bulky beasts were split between increasing the rate and increasing the duration of their growth. While the 2,500-pound Ceratosaurus picked up the pace of its development, for example, reaching full size after several years, its close relative Majungasaurus prolonged the period, reaching a similar size after two to three decades.

Full of possibilities

The researchers also found a similar split among the 40 percent of theropods that became smaller over evolutionary time, including the sickle-clawed raptors. Like their larger relatives, these downsizing dinosaurs displayed multiple growth patterns, including decreased growth rates and decreased growth durations. But whatever their method, shrinking down was an essential step, as some of these lineages eventually evolved into birds, which needed lightweight bodies to take flight.

According to Thomas Cullen, a paleontologist at Auburn University who was not involved in the study, the analysis suggests that the theropods developed different growth mechanisms depending on their surroundings. “Rather than there being a single pathway of growth,” Cullen says, “it’s likely that a range of different ecological factors drove changes in body sizes.”

Though Ceratosaurus and Majungasaurus both became giants, for instance, differences in their environments encouraged their different styles of development. While competition with allosaurs and other fearsome foes drove the accelerated growth spurts of Ceratosaurus in the Jurassic, an absence of competition enabled the more leisurely and energy-efficient growth of Majungasaurus, which was unrivaled in its home turf of Cretaceous Madagascar.

According to D’Emic, the study sheds light on much more than the lives of the theropods, with the results hinting at the diverse developmental strategies that have been available to animals throughout history. “We can’t just study the evolution of growth by looking at groups of animals alive today,” D’Emic says, stressing that human hunting and climate change have obscured the full gamut of growth possibilities. Instead, a comprehensive understanding of development must consider creatures from the past as well as the present, with the theropods and their bones revealing only one small piece of the puzzle of animal size.