In 1906, the French company Société L. Dutheil, R. Chalmers et Cie (Dutheil-Chalmers) began developing aircraft engines for early aviation pioneers. The company was headquartered in Seine, France and was founded by Louis Dutheil and Robert-Arthur Chalmers. Although most of their engines were water cooled, the Dutheil-Chalmers’ horizontal aviation engines may have been the first successful versions of the horizontal type that is now used ubiquitously in light aircraft. Continuing to innovate for the new field of aviation, Dutheil-Chalmers soon developed a line of horizontal, opposed-piston engines.

Taken from the Dutheil-Chalmers British patent of 1909, this drawing shows the layout of the horizontal, opposed-piston engine. The dashed lines represent the bevel-gear cross shaft that synchronized the two crankshafts.

On 23 November 1908, Dutheil-Chalmers applied for a French patent 396,613 that outlined their concept of an opposed-piston engine, as well as other engine types. The French patent is referenced in British patent 26,549, which was applied for on 16 November 1909 and granted on 21 July 1910. In the British patent, Dutheil-Chalmers stated that the engine would have two crankshafts. The output shaft would not be a power shaft that connected the two crankshafts. Rather, the crankshafts would rotate in opposite directions (counter-rotating), and a propeller would mount directly to each crankshaft. This is the same power transfer method used in the SPA-Faccioli opposed-piston aircraft engines. While the Dutheil-Chalmers and SPA-Faccioli engines shared a similar concept and were built and developed at the same time, there is no indication that either company copied the other.

The Dutheil-Chalmers opposed-piston engines are sometimes referred to as Éole engines. It is not clear if Dutheil-Chalmers marketed the engines for a time under a different name or if Éole was just the name they gave to their line of opposed-piston engines. Éole is the French name for Aeolus, the ruler of the winds in Greek mythology. The engines were primarily intended to power airships. The two counter-rotating propellers would cancel out the torque associated with a single propeller on a standard engine. In addition, the opposed-piston engine’s two-propeller design did not require the heavy and cumbersome shafting and gears necessary for a conventional single-crankshaft engine to power two propellers.

Top and side view drawings of the four-cylinder, opposed-piston engine. The drawings show no valve train and differ slightly from photos of the actual engine, but they give an idea of the engine’s general layout.

Four different horizontal, opposed-piston engine sizes were announced, all of which were water-cooled. Three of the engines had the same bore and stroke but differed in the number of cylinders used. These engines had two, three, and four cylinders. Each had a 4.33 in (110 mm) bore and a 5.91 in (150 mm) stroke, which was an 11.81 in (300 mm) stroke equivalent with the two pistons per cylinder. The two-cylinder engine displaced 348 cu in (5.7 L) and produced 38 hp (28 kW) at 1,000 rpm. The engine weighed 220 lb (100 kg). The three-cylinder engine displaced 522 cu in (8.6 L) and produced 56 hp (42 kW) at 1,000 rpm. The engine weighed 397 lb (180 kg). The four-cylinder engine displaced 696 cu in (11.4 L) and produced 75 hp (56 kW) at 1,000 rpm. The engine weighed 529 lb (240 kg). It is not clear if any of these engines were built.

The fourth engine was built, and it was the largest opposed-piston engine in the Dutheil-Chalmers line. The bore was enlarged to 4.92 in (125 mm), and the stroke remained the same at 5.91 in (150 mm)—an 11.81 in (300 mm) equivalent with the two pistons per cylinder. The four-cylinder engine displaced 899 cu in (14.7 L) and produced 97 hp (72 kW) at 1,000 rpm. Often, the engine is listed as producing 100 hp (75 kW). The four-cylinder engine weighed 794 lb (360 kg).

This Drawing illustrates the front of the Dutheil-Chalmers opposed-piston engine. Note the cross shaft that synchronized the two crankshafts. The gear on the cross shaft drove the engine’s camshaft. The pushrods, rockers, and valves are visible.

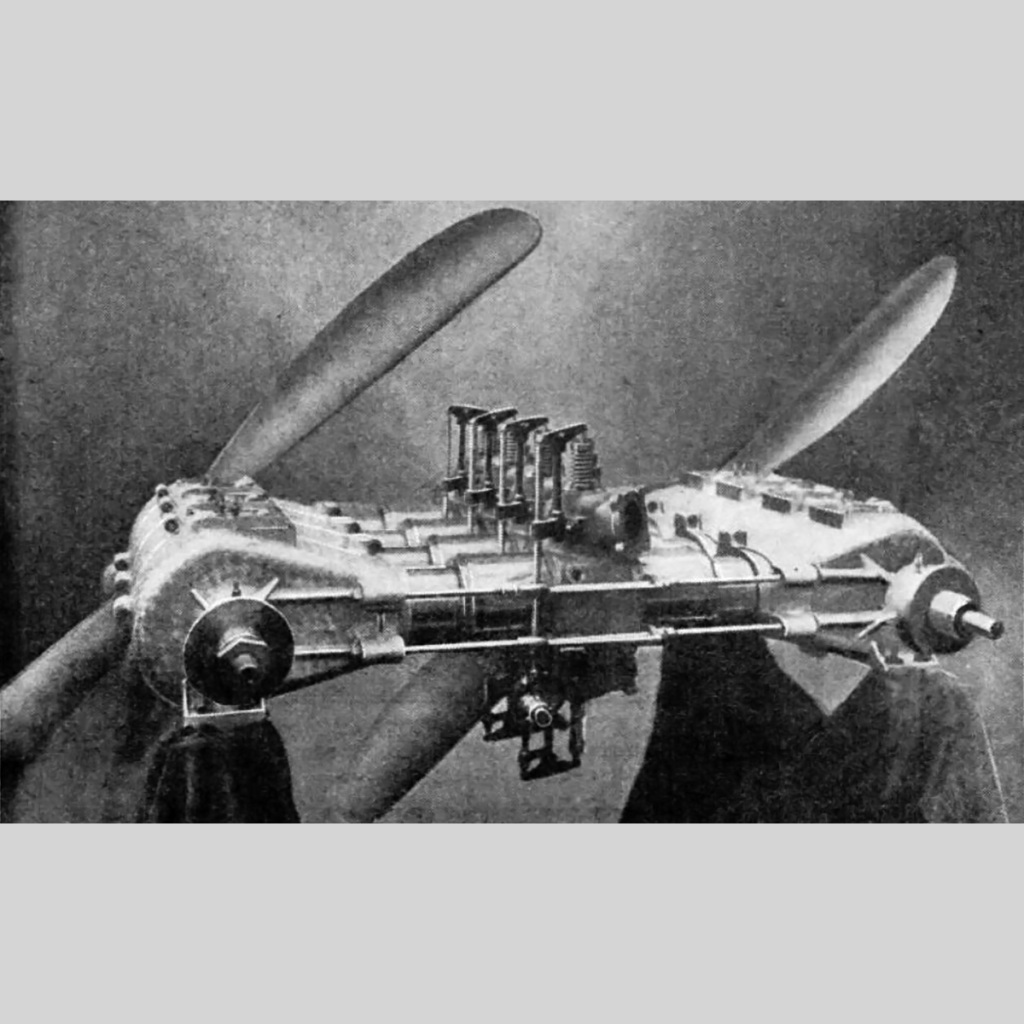

Only the 97 hp (72 kW) engine was exhibited, but it was not seen until 1910. The engine was displayed at the Paris Flight Salon, which occurred in October 1910. The engine consisted of four individual cylinders made from cast iron. The horizontal cylinders were attached to crankcases on the left and right. Threaded rods secured the crankcases together and squeezed the cylinders between the crankcases. Each crankcase housed a crankshaft, and the two crankshafts were synchronized by a bevel-gear cross shaft positioned at the front of the engine. A two-blade propeller was attached to each crankshaft. The propellers were phased so that when one was in the horizontal position, the other was in the vertical position.

Near the center of the cross shaft was a gear that drove the camshaft, which was positioned under the engine. The camshaft actuated pushrods for the intake valves on the lower side of the engine and the exhaust valves on the upper side of the engine. The pushrods of the intake valves travel between the cylinders. All of the pushrods acted on rocker arms that actuated the valves positioned in the middle of the cylinder. Each cylinder had one intake and one exhaust valve.

No information has been found that indicates any Dutheil-Chalmers Éole opposed-piston engines were used in any airship or aircraft. Still, it is an unusual engine conceived and built at a time of great innovation, not just in aviation, but in all technical fields.

The 97 hp (72 kW), four-cylinder, eight-piston engine on display at the Paris Flight Salon in 1910. The engine has appeared in various publications as both a Dutheil-Chalmers and an Éole. Note the rods that secured the crankcases together. What appears to be the camshaft can be seen under the engine. (alternate view)