The Mariana Trench is the deepest point on Earth. Image: Shutterstock/DOERS

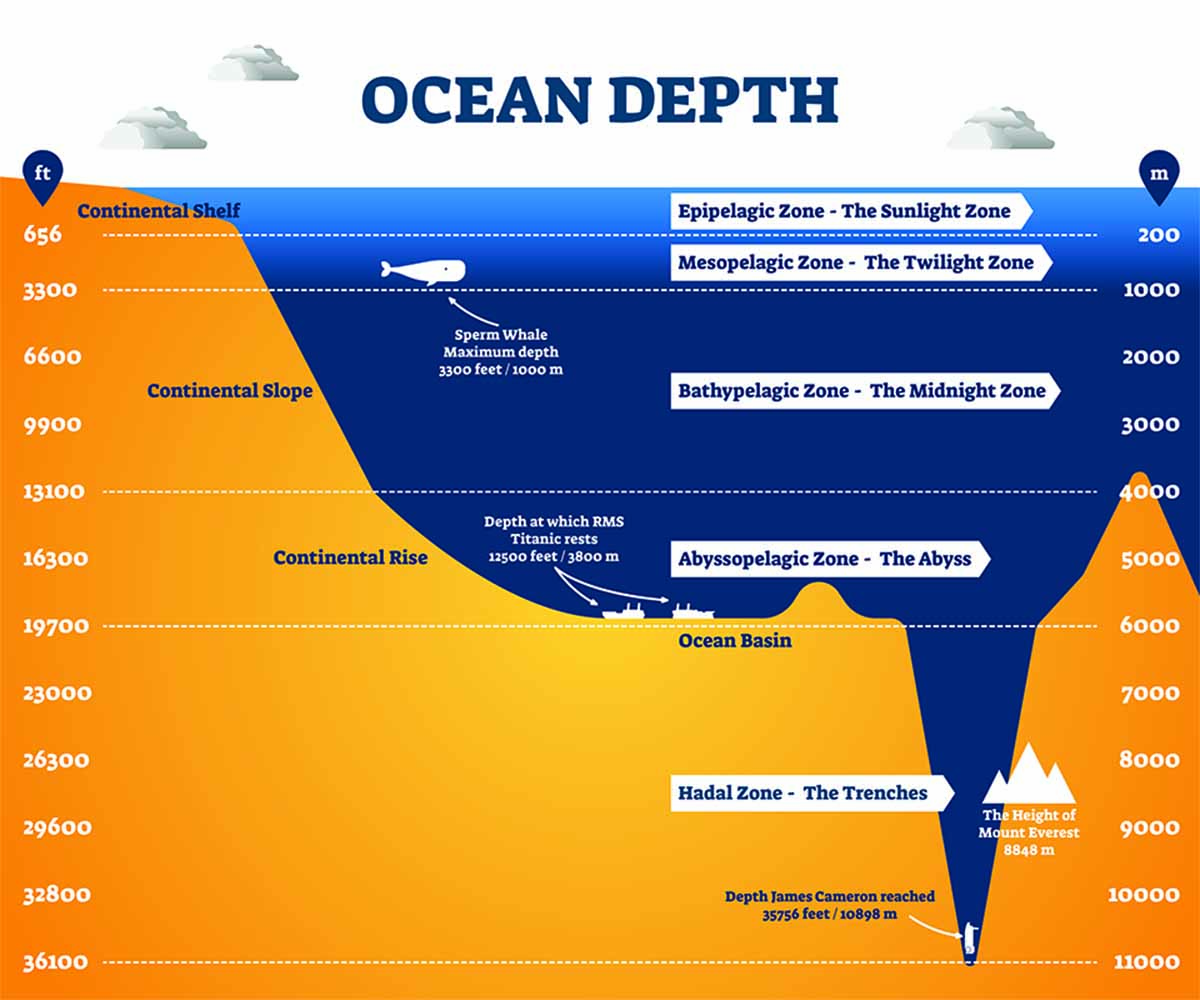

The Mariana Trench is an oceanic trench that sits to the south-east of the Mariana Islands in the western region of the Pacific Ocean. Its deepest point is thought to be approximately 11,034 metres below the surface of the sea, although the very lowest section to have been accurately measured, known as Challenger Deep, lies at 10,911 metres. This makes Challenger Deep the deepest-known point on the Earth’s seabed. If Mount Everest were located here, it would still sit two kilometres below the waves.

Oceanic trenches are depressions in the sea floor and are a common feature of the Earth’s plate tectonics – there are more than 50 major ocean trenches worldwide, although the deepest (including the Mariana Trench) can be found along the Ring of Fire, a line of active volcanoes that encircles the Pacific Ocean. Trenches mark the location of convergent plate boundaries, where two plates collide, forcing one beneath the other and creating a deep chasm or trench in the Earth’s surface.

The Mariana Trench was first discovered in 1875 by the crew of the British ship H.M.S Challenger (after which Challenger Deep was named) and was explored again by H.M.S Challenger II in 1951, with a better degree of accuracy. Since then, measurements of the trench have been collected and it is estimated that as well as its astonishing depth, the trench is 2,550 kilometres long and 69 kilometres wide.

From the ocean’s surface to the dark depths below, the climate of the trench is both varied and sometimes extreme. It is made up of active mud volcanoes and bubbling pockets in the floor that release sulphur and carbon dioxide. At the bottom of the trench the temperature sits between 1–4℃ and no light penetrates the area. Yet even in conditions of extreme darkness and pressure (the water pressure at the bottom is more than 1,071 times that found at sea level) life can still thrive.

A mud sample taken at Challenger Deep by Japanese oceanographers revealed approximately 200 different species of microorganism, including types of microscopic plankton and shells. The most common creatures in the trench include saucer-sized, single-celled xenophyophores, which feed on sediment. There are also amphipods, which are large shrimp-like scavengers, and small sea cucumbers called holothurians.

Larger species have also been found living at remarkable depths within the trench, including the hadal snailfish – a small, pink and completely scaleless species found living at depths of almost 8,200 metres (27,000 feet). With skin so transparent that you can see right through to its liver, it holds the record for the deepest fish captured on the seafloor. The deep-sea dragonfish – a predator that features a giant set of teeth much bigger than its body – also plumbs the depths between 213 to 1,828 metres. In between, researchers have identified dumbo octopus, zombie worms and deep-water jellyfish.

As humans, we are unable to venture very far into the Mariana Trench due to the bone-crushing pressure deep beneath the ocean’s surface. It is so strong that most deep-sea machinery struggles to function, making data collection very difficult. Although scientists and oceanographers are always looking for new ways to gather this information, there is likely plenty more to discover.

Only a handful of people have successfully completed a dive into the furthest reaches of the Mariana Trench. The first descent happened on 23 January 1960 and was carried out by US navy lieutenant Don Walsh and Swiss oceanographer and explorer Jacques Piccard. They dove for an impressive five hours to a depth of 10,912 metres (although more accurate measurements would later reveal the trench to be very slightly shallower) in a submersible called the Trieste, providing scientists with more information about its conditions and the potential for research. On looking out of their porthole, Walsh and Piccard saw thousands of glowing creatures: ‘Bioluminescence is rampant in the abyss,’ Walsh later said, ‘even out where we were, which is not a very thickly populated part of the ocean, because there aren’t that many nutrients out that far from land.’

More than 50 years later, in 2012, filmmaker James Cameron made history by becoming the first person to make a solo dive to Challenger Deep. His descent took 70 minutes. Cameron’s submersible – the Deepsea Challenger – was much more sophisticated than the earlier Trieste. Cameron arrived at the bottom with the technology to collect scientific data and specimens not possible during the earlier mission. Cameron spent hours hovering over Challenger Deep’s desert-like seafloor collecting samples and video as he went.

More recently still, in May 2019, American naval officer Victor Viscovo completed the deepest manned sea dive ever recorded, reaching 10,927 metres at the southern end of the trench. Viscovo’s expedition gave researchers new information, including the fact that the bottom of the trench isn’t flat as once thought but rather made of planes and ridges. Four new species were discovered along with an unexpected encounter: a plastic bag and some sweet wrappers.

In the future, most exploration of the trench will take place using unmanned vehicles, but there will always be those looking to test the limits of both man and machine.

In addition to the discovery of plastic in the trench, it is known to contain other pollutants. While sampling amphipods from the Mariana and Kermadec trenches, a research team led by scientists at Newcastle University discovered extremely high levels of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in the organisms’ fatty tissues. These included polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), chemicals commonly used as electrical insulators and flame retardants, according to a study published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution. These POPs were released into the environment through industrial accidents and landfill leakages from the 1930s until the 1970s, when they were finally banned.

A 2018 paper in the journal Geochemical Perspectives also found that microplastics are common in the lowest waters of the Mariana Trench.

Despite the pioneering research that has taken place in the Mariana Trench, it remains largely unexplored. This is true for the rest of the ocean too. Scientists believe that humans have only adequately explored around eight per cent of the world’s oceans, although the Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project, which is working to collect all available data on the world’s oceans, has mapped out roughly a fifth of the ocean floor. The scope of what is still out there for us to find, however, is almost incomprehensible.