A clawed, flightless bird that went extinct in New Zealand in the late 13th century might be brought back to life, claim scientists at Harvard University.

Nearly three decades ago, archaeologists exploring a cave system on Mount Owen in New Zealand discovered a dinosaur-like claw with flesh and scaly skin. After testing it proved to the a 3,300-year-old mummified remains of an upland moa (Megalapteryx didinus). A DNA analysis published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences established that there were at least “ten species of moa which appeared around 18.5 million years ago” but they were all wiped from existence in what scientists call “the most rapid, human-facilitated megafauna extinction documented to date.”

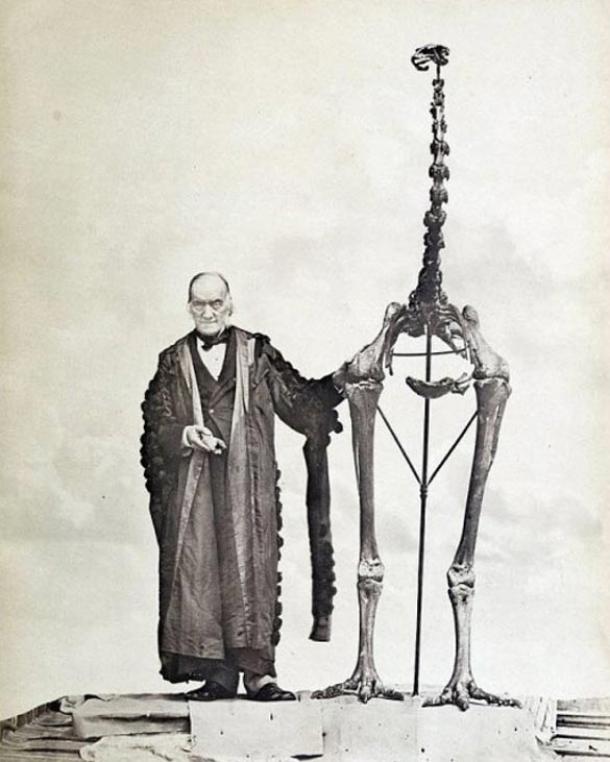

Sir Richard Owen standing next to a moa skeleton and holding the first bone fragment belonging to a moa ever found. (Public domain)

Using DNA recovered from the toe, Harvard scientists have now mapped and compiled the first almost complete genome of a “little bush moa,” moving closer to the possibility that extinct genomes will soon become “de-extinct.” The whole idea of bringing “vanished species back to life by slipping the genome into the egg of a living species,” has been regarded by some reviewers as equal to the dark fictional works of Dr Frankenstein, while to others, it has been described in a lighter light as being ‘Jurassic Park’-like,” according to an article on statnews.com.

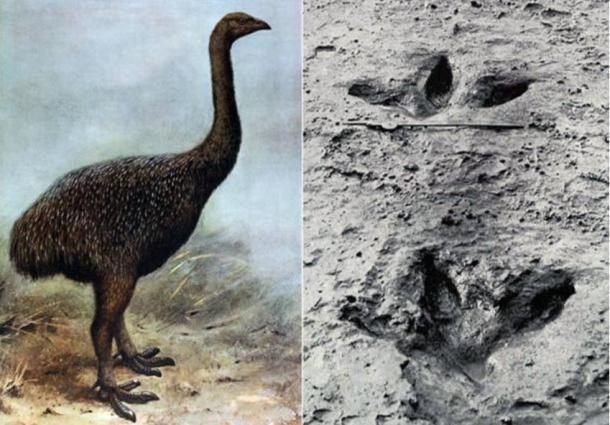

Left: Illustration of a Moa. Right: Preserved footprint of a Moa (public domain)

Let’s not enter the moral debate, for that is wholly subjective, and look closer at the processes and innovations of a team of scientists at Harvard University. Aiming to “resurrect vanished species”, the work of Cloutier et al., (2018) on the DNA of the little bush moa was recently published in a non-peer-reviewed paper. The DNA was reconstructed from the sample taken from the creature’s toe but scientists know that a lot of genetic restructuring is needed before a species can be ‘revived’. For the moa, scientists have said they may have to use a 1-pound emu egg to incubate it.

Work has already been ongoing to map the passenger pigeon genome and the woolly mammoth. Revive & Restore, in collaboration with the U.C. Santa Cruz Paleogenomics Lab, has sequenced DNA from 37 passenger pigeons, including two whole genomes (see paper). Speaking of this latest project to reporters at statnews.com, Morten Erik Allentoft of the Natural History Museum of Denmark, an expert on moa DNA said it is “a significant step forward.” As well as the woolly mammoth and passenger pigeon, among the “nearly complete” extinct genomes, scientists have almost completed two of our human cousins, Neanderthals and Denisovans, the dodo, the Tasmanian tiger and the great auk, which dyed out in the North Atlantic in the mid-19th century.

Scientists have almost completed the mapping of the Tasmanian Tiger genome, another extinct species that may soon be revived (public domain).

According to Harvard’s Alison Cloutier, the little bush moa team tried to match “900 million nucleotides, scattered across millions of DNA pieces, and tried to match them to specific locations on the genome of the emu, a close relative of all nine moa species.” Bird genomes, including the eight other extinct moa species, “have similar genes for particular traits tend to be on the same chromosome and arranged relative to other genes in a similar way,” according to the statnews.com article.

Similarly, The Mammoth Project, which is being conducted by Revive & Restore in collaboration with Harvard’s George Church Lab, has been studying elephant chromosomes to better understand how mammoth DNA might be organized (see paper). Scientists believe that herpes infections killed off the mammoth and if it was made ‘de-extinct’, its immune system could be enhanced to resist this virus. You might be asking, like I did, wasn’t all this DNA and genome mapping sorted out “before” the 1996 birth of Dolly the Sheep at the Roslin institute in Scotland?

“Kind of” is the answer, the problem is, putting DNA into an egg is infinitely more difficult than fertilizing mammals. The cloning method applied to make Dolly the Sheep is fine for a mammalian eggs, “but that doesn’t work in birds — “at least so far,” Brand told reporters.

There is no doubt the final parts in the cloning puzzle will be solved, and given enough time, maybe not in our lifetime, a country or a private enterprise will inevitably work out how to clone us.