The novel won a Pulitzer; part of the TV miniseries was filmed on a ranch in Texas.

Horses stampede through the town of Lonesome Dove. Photo by Esparza

After the Civil War, an estimated 30,000 cowboys pushed nearly 10 million Texas Longhorns over trails to northern ranges and markets. The cattle drives braved Comanches, rustlers, stampedes, and hazardous rivers.

The Old West of those journeys-the Chisholm Trail, The Goodnight-Loving, the Shawnee, and the Lone Star Trail to Montana-has been kept alive by such Hollywood cattle drive classics as The Long Trail, American Empire, North of 36, San Antonio, and Red River.

In April and May of 1988, Texas novelist Larry McMurtry’s Pulitzer Prizewinning novel, Lonesome Dove, was filmed in Texas (and later in New Mexico) for CBS Television. The miniseries will be broadcast this fall. The tale follows an epic cattle drive from the banks of the Rio Grande to the wilderness grasslands of Montana in the 1870s.

Actress Diane Lane and actor Robert Urich. Photo by Esparza

The television film features Academy Award actor Robert Duvall, who won an Oscar in 1981 for his interpretation of a country-western singer in Tender Mercies. In Lonesome Dove, Duvall plays Augustus McCrae, a former Texas Ranger surviving in the hardscrabble border town of Lonesome Dove. Gus McCrae’s partner in the Hat Creek Cattle Co. & Livery Emporium is his old Ranger sidekick, Woodrow Call. Portraying Call is Tommy Lee Jones, an Emmy Award winner. Jones owns a ranch in San Saba, Tex., where he was born.

In the role of Clara, the “good woman” Gus McCrae cannot forget, is Angelica Huston. Lorena Wood , the young “sporting woman” who accompanies the trail drive to Montana, is played by Diane Lane.

The CBS miniseries is directed by Australian Simon Wincer, whose most recent work was the network miniseries Bluegrass, although Wincer is best remembered for his feature film Phar Lap, the story of an Australian race horse.

The film company of Motown Productions/Robert Halmi Inc. chose the Bill Moody Ranch outside Del Rio for the set of the town of Lonesome Dove, a setting with all the mesquite, hackberry, prickly pear, guajillo, and cenizo brush of the borderlands. In the past, the Moody Ranch has provided other locations for the film industry. The former set for the town of Gonzales in the TV miniseries Houston, the Legend, starring Sam Elliott, was reconstructed for Lonesome Dove as a Colorado river scene complete with dock and boat.

At nearby Brackettville, Happy Shahan’s Alamo Village old-time movie set hosted certain Lonesome Dove scenes. Founded in 1957 by John Wayne for his production of The Alamo, the facilities represented San Antonio of the 19th century for this production.

At Del Rio, the Moody Ranch supplied several hundred crossbred cattle and Corrientes and also some remuda horses. Foreman Charley Helms said, “We had to do preparatory work training the horses for the remuda scenes, at $10 a day. For the actual filming, it was $20a day.”

The Moody horses were sprayed for the boophilus fever tick from Mexico to prevent the outbreak of tick fever and a potential loss of millions of dollars to the American cattle industry.

The Moody Ranch lies in the United States government’s tick quarantine buffer zone along the Rio Grande. Livestock leaving this zone must be sprayed or dipped with pesticides. This Department of Agriculture tick eradication program spreads along the 100 miles of Rio Grande banks from Brownsville to Del Rio.

The Lonesome Dove sector fell under the supervision of Marion Forbes of Del Rio, a south Texas cowboy who once gathered cattle for inspection on the King Ranch. Under Texas law, Forbes was obliged to see that all the horses used in Lonesome Dove –whether Moody stock or movie horses trailered from California– were sprayed with Del-Nav, a solution effective in killing the cycle of the fever tick for 14 days. Cattle also required parasite eradication. At the Moody Ranch’s old Sycamore Creek vat and quarantine holding pens, Marion “charged” the dipping vat with the pesticide Co-Ral. The cattle were forced to swim through the vat. If even one “hot” tick (carrying the disease) failed to die, an epidemic of tick fever could have threatened the United States.

The tick eradication program began in 1906, but at the time of Lonesome Dove –the 1870s– no such protection existed. Mexican and Texian cattle driven up the trail were immune to the tick fever, as Mexican cattle still are, but the old trail cattle carried the disease-bearing parasites north.

Working with Marion Forbes in the spraying and dipping of the movie livestock was Jimmy Medearis, the film ‘s livestock coordinator and head wrangler from Castaic, California.

A member of the movie industry for 17 years, Medearis is a member of Teamster’s Union 399 for stuntmen and wranglers. His job on Lonesome Dove involved everything from contracting movie horses at A&R Livestock in Lake View Terrace, Calif. , to supplying saddles, harness, and other equipment as well as rolling stock including covered wagons- for the film. Once the production was under way, Medearis was on the set warming up his own AQHA rope horse, Mastercharge, for use by Robert Duvall.

Medearis, whose wife, Sharon, is a professional barrel racer, was raised in Pasadena, Texas. He rode rough stock in rodeo before becoming a trick rider and then stuntman in the movies. Among other films, he has worked in The Long Riders, Mountain Men, and the TV miniseries North and South.

Safety was of prime importance on the Lonesome Dove set, but stampedes are a bit tricky to film, said Medearis, “because you have to coordinate with everyone in the movie. Sometimes we rehearse stampedes. The cattle are never running as fast as they appear on the screen. You might call it a ‘controlled stampede.’ We don’t leave anything to chance.”

The only injury on the Lonesome Dove set was a mesquite thorn infecting the hand of wrangler Steve Manning of Pinedale, Wyo., who got his first taste of Texas brush popping at Moody’s.

In addition to handling livestock, one of the concerns of-wranglers such as John Hudson, a calf roper from Salinas, Calif., was to give riding instructions to those cast members new to the saddle. And to equip them with understanding, babysitter movie horses like Fury, who is 30 years old. “He’s been in more westerns than John Wayne,” Hudson said. Fury bore years of traders’ brands, including the N of the Navajo Indian nation. Fury’s mellow, jug-headed, feather-fetlocked appearance makes him desirable for westerns. He’s typey, like the rawboned cayuses in Charlie Russell’s paintings of the frontier.

Both Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones are experienced horsemen, and the saddle Duvall rode was reportedly built for Kris Kristofferson in the pioneer epic Heaven’s Gate, filmed in Montana.

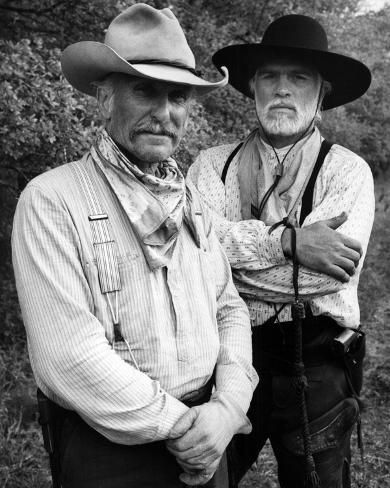

Robert Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones, the two lead actors in the movie.

David Little, a Texas wrangler who also had a small acting role in Lonesome Dove, said that when he was a kid growing up in Chireno, Tex., “I used to ride my horse to the movie theater and tie up and go in and watch Roy Rogers.I told my mama that when I grew up I wanted to be a cowboy and work in the movies.” After 20 years of forking rodeo bareback horses, saddle broncs, rank bulls, and 10 years of doing movie work horseback, David Little has Roy Rogers to thank for “27 broken bones!”

Rodeo hand Jimmy Sherwood of Los Angeles, another wrangler on the set, said, “One of the reasons I like this movie work is I get to drive big herds and cowboy the way they used to a hundred years ago.”

It all fits with McMurtry’s quote from T.K. Whipple in the preface to the novel: “All America lies at the end of the wilderness road, and our past is not a dead past, but still lives in us. Our forefathers had civilization inside themselves . . . We live in the civilization they created, but within us the wilderness still lingers. What they dreamed, we live, and what they lived, we dream.”