In 1930, Australian driver Norman Leslie “Wizard” Smith attempted to set a Land Speed Record (LSR) on Ninety Mile Beach (which is actually 55 miles / 88 km long) in New Zealand. His car, the Anzac, was built by well-known race driver, engineer, and fellow Australian, Donald James Harkness. Harkness was also the riding mechanic for the Anzac record runs. Smith and Harkness knew the 360 hp (268 kW) Anzac was not capable of setting an absolute speed record for the flying mile (1.6 km), but they hoped to set national records for Australia and New Zealand as well as a 10-mile (16-km) world record. Technically they were successful, but the 10-mile (16-km) record was not verified on account of a single run being made without a return run in the opposite direction. The Anzac was also used to gain experience that would be applied to the design and construction of a much more powerful car capable of 300 mph (483 km/h).

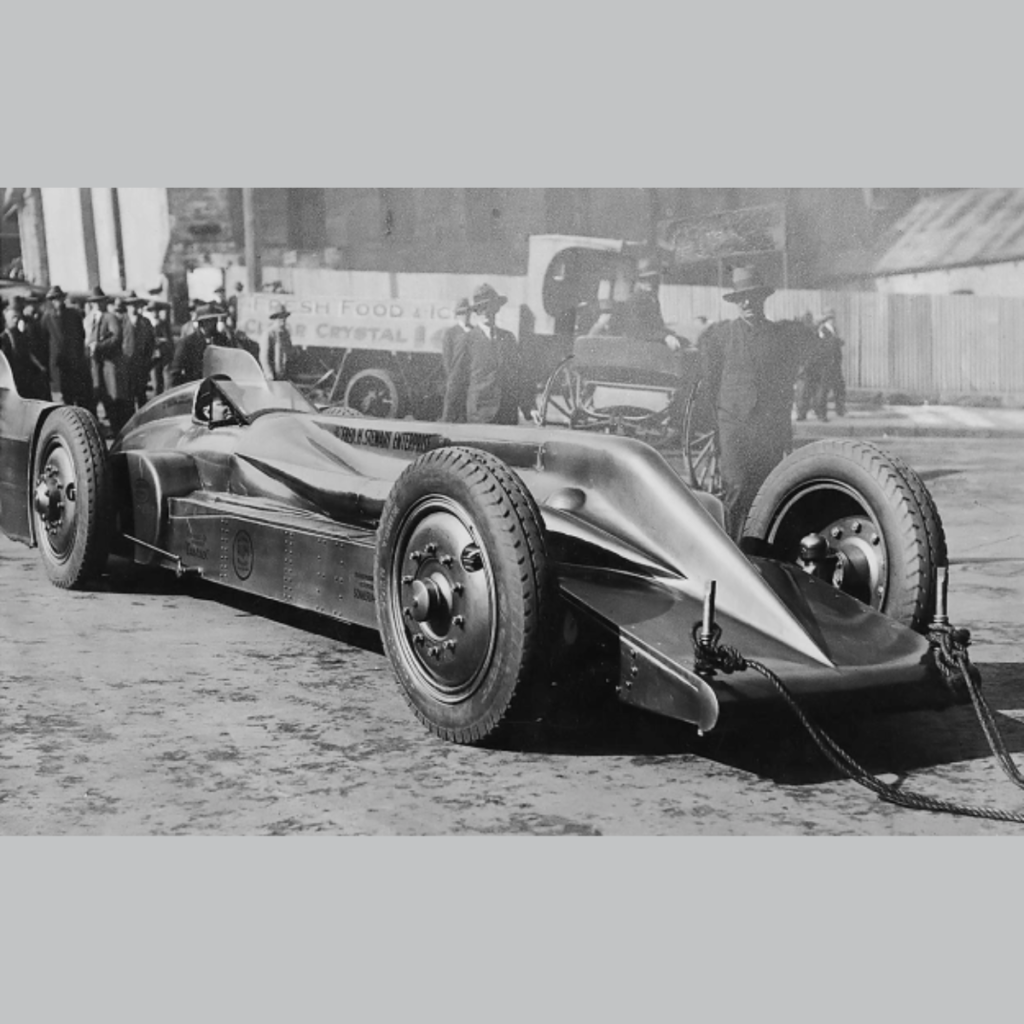

Norman “Wizard” Smith and Don Harkness pose with the nearly completed Fred H. Stewart Enterprise in 1931. Note how the body sloped up in front of the cockpit. This was done in an attempt to increase downforce at the center of the car to aid stability at high speeds.

Setting world speed records is an expensive endeavor. While Smith and a few friends funded most of the Anzac, the much larger and faster LSR car would need financial resources beyond that which Smith and his partners could provide. Fortunately, Smith was able to leverage his success with the Anzac and as a racer to gain the financial backing of Australian businessman and politician Frederick Harold Stewart. The one stipulation set by Stewart was that the new LSR car be named the Fred H. Stewart Enterprise. The car was originally to be named Anzac II, but at the time, Australian policy stated that ANZAC can only refer to the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps and cannot be used in any other fashion without prior permission. As a result, Smith had to take the name off his previous racer and select a different name for the new racer. The financing terms were agreed upon, and Smith and Harkness focused on building the LSR car, the Fred H. Stewart Enterprise (Enterprise).

To power the Enterprise, Smith and Harkness needed an engine much more powerful than anything they could obtain themselves. They sought a 1,600 hp (1,193 kW) Rolls-Royce R engine developed for the 1929 Schneider Trophy contest. The Enterprise team turned to the Australian government for assistance, and the Australian Prime Minister, James Scullin, reached out to the British government. Ultimately, the British Air Ministry loaned Smith the latest Napier Lion VIID W-12 engine, capable of 1,450 hp (1,081 kW) at 3,600 rpm. This was the same type of engine that Malcolm Campbell would soon install in his latest Blue Bird revision, the Campbell-Napier-Railton Blue Bird. At the time, the engine’s particulars were considered secret, and the Air Ministry stipulated that only Smith, Harkness, and two Enterprise crew members be allowed to work on it. Some reports indicate that a deposit of £5,000 was required, which was paid by Stewart, and that a Rolls-Royce engine was expected right up until the crate was opened to reveal the Napier. The taller and less-powerful Lion necessitated a slight redesign of the Enterprise, and the car’s estimated top speed decreased to 280 mph (451 km/h).

The Enterprise under construction at Harkness & Hillier Engineering Works. Smith is sitting, with Harkness at his right. In front of the Napier Lion engine is Smith’s wife, Harriet. Note the screw jacks at the rear of the car, the leaf-spring rear suspension, and the size of the frame rails.

The Fred H. Stewart Enterprise was designed by Harkness and built at the Harkness & Hillier Engineering Works in Five Dock, near Sydney. The car resembled the 930 hp (694 kW) Irving-Napier Golden Arrow, which Henry Segrave had used to set the then-current LSR at 231.362 mph (372.341 km/h) on 11 March 1929. Like the Golden Arrow, the Enterprise had a chisel-shaped front end leading to a tightly-cowled Lion engine. Its wheels were set outside of the bodywork, and the cockpit was positioned toward the rear and flanked by driveshafts connected to the rear axle. One major difference in appearance was that the Enterprise had two stabilizing tails, each extending back behind the rear wheels. With an additional 520 hp (388 kW) and 17-percent less frontal area, Smith and Harkness thought the Enterprise would go faster than the Golden Arrow.

The Enterprise’s chassis consisted of two large frame rails connected by various cross members. Each corner of the frame had provisions for a screw jack to easily raise the car. The Lion engine was nestled between the frame rails and connected to a three-speed transmission. Output from the transmission was split into two drive shafts that passed through armor-plated housings on both sides of the driver’s seat. Each drive shaft connected to a drive box that was connected to a rear wheel. The front wheels appear to have had very minimal suspension, and the rear wheels were supported by leaf springs positioned above the frame. The frame, powertrain, and suspension were all designed to minimize the Enterprise’s height.

At its christening on 26 October 1931, the Enterprise was fitted with relatively small aerodynamic fairings behind the rear wheels. It is not clear if this was Harkness’ final vision for the car, as other photos show no front fairings at all.

Separate drag links extended from the steering box positioned in front of the cockpit to the front wheels. A tie rod connected the front wheels together. The steering system enabled 20 degrees of wheel movement. A close-fitting body covered the Enterprise. The body was designed to push the middle of the car down at high speeds. A hump on each side of the cockpit enclosed the suspension for the rear wheels. The humps tapered down to form a wedge at the rear of the car. The body surrounding the cockpit tapered back to a point. The stabilizing tail fins, built from steel tube frames and covered with fabric, extended behind the rear wheels. A flat-plate windscreen was mounted at an angle just before the cockpit, and the fuel tank was positioned behind the cockpit.

The Enterprise was 26 ft (7.92 m) long, 69 in (1.75 m) wide, 36 in (.91 m) tall in front of the cockpit, 42 in (1.07 m) tall at the top of the cockpit, and 48 in (1.22 m) tall at the tail fins. The car had 7.5 in (191 mm) of ground clearance and weighed around 6,700 lb (3,039 kg). Only the rear wheels had provisions for brakes. Smith purchased a set of special Dunlap slicks guaranteed to 310 mph (500 km/h) for the speed runs. These tires were 37 in (940 mm) tall and 7 in (178 mm) wide. Like Smith’s Anzac, the Enterprise was finished in a golden color and had Australian flags painted on its tails. While the Enterprise was being built, Campbell set a new flying-mile (1.6-km) LSR at 245.736 mph (395.474 km/h) on 5 February 1931.

The Enterprise without any front wheel fairings and with Smith in the cockpit. As designed, the Enterprise was a rather sleek machine. Note the brake link extending from the cockpit back to the rear wheel and the lack of brakes on the front wheels.

The Enterprise was anticipated to be completed around February 1931. However, delays with the car’s construction along with separate business matters preoccupying Smith, Harkness, and everyone else involved with the car, resulted in the Enterprise not being completed until the end of 1931. During this time, the Auckland Automobile Association built a garage at Hukatere, near the mid-point of Ninety Mile Beach. The garage was constructed for Smith and for others who might pursue future record attempts, as Malcolm Campbell was considering using Ninety Mile Beach. A side effect of the new garage was that Smith would no longer use Star Garage in Kaitaia, and some locals saw this as a slight against the town. This issue, combined with the lengthy delays, made many on the northern tip of the North Island have a general disdain for Smith and his record runs.

The incomplete Enterprise made a few public appearances in April and August 1931. Part of the delay in finishing the car was caused by a disagreement between Harkness and Smith on how to cool the Napier Lion. Harkness had designed the Enterprise to use ethylene glycol chemically cooled in a heat exchanger by methyl chloride (Chloromethane or Refrigerant-40). This method would leave the car aerodynamically clean without incorporating any radiators. Because of the relatively untried nature of chemical cooling and its high cost, Smith wanted to employ conventional water cooling with a radiator housed in a streamlined fairing at the front of the car, which was the method used on the Campbell-Napier-Railton Blue Bird. It should also be considered that Napier may have demanded that water-cooling be used on the loaned engine. Frustrated and running out of time, Harkness designed and constructed a pair of conventional radiators that mounted just before the front tires. Fairings mounted behind the front tires would serve as water reservoirs for the cooling system. With the exception of bracing for the radiators, this left the front of the car aerodynamically clean, and the radiators probably did not create any more drag that the tires just behind them. However, the system looked cobbled-together and very unrefined. Smith felt Harkness’ design was totally inadequate.

The Enterprise most likely seen arriving in Hukatere. The truck in the background transported the car from Awanui to Hukatere. The large radiator at the front of the car has been shrouded in a canvas cover. The new reservoir fairings are attached behind the front wheels, but the tail fins are not installed.

When the Enterprise was christened on 26 October 1931, it still had no visible means of cooling the engine, and small fairings behind the front wheels were installed for aerodynamic purposes only. The strain of everything had become too much, and Harkness suffered a nervous breakdown at the beginning of November. The Enterprise was started for the first time on 18 November, and preparations were made to ship the car to New Zealand.

At the request of Smith, and without the knowledge of Harkness, Lawrence James Wackett, perhaps Australia’s foremost authority on aviation and aerodynamics at the time, had analyzed the Enterprise’s cooling system and submitted a report to Smith a few days before the trip to New Zealand. Wackett had noted that the radiators did not have sufficient capacity to cool the Lion engine and that their installation would likely fail at high speed. When the Enterprise arrived in Auckland, New Zealand on 8 December, the disagreement on engine cooling had yet to be resolved. The radiators were not installed, but they had been shipped with the car to be added once the Enterprise arrived in New Zealand.

Around 10 December 1931, the Enterprise was fully assembled with its twin radiators and underwent a safety inspection, which it failed. The mounting of the radiators was deemed insufficient and was predicted to collapse at high speeds. Harkness persisted with the twin radiator design, and the tremendous strain that Harkness was under really began to show—political maneuvering brought an end to his company’s main source of income; his other business ventures were failing, and he was experiencing issues in his personal relationships. With the failed safety inspection in hand, Smith made his move and served Harkness with a restraining order, ousting him from further involvement with the Enterprise. Smith was not happy about the situation, but he felt that his priority needed to be fixing the Enterprise so that he could proceed with record attempts. Harkness stayed in Auckland while the rest of the party moved north, and he left New Zealand around 8 January 1932.

The Enterprise being towed out of the newly-constructed garage at Hukatere. The large, odd radiator truly spoiled the car’s looks and aerodynamics. Note the Dunlop road tires.

Before leaving Australia, Smith had made arrangements to design, build, and mount a new radiator to the Enterprise. Since Smith now had control of the car and knew the twin radiator design was flawed, he moved the Enterprise to an Auckland garage to fabricate a conventional radiator. The radiator work was conducted somewhat secretly, and the changes to the Enterprise surprised many when the car arrived in Awanui by skiff on 3 January 1932. The massive rectangular radiator absolutely ruined the lines of the Enterprise, but the radiator was an emergency fix done with little time. Smith defended the cooling system, comparing it to the type then used by Campbell on the latest Blue Bird. While the configuration was similar, the implementation on the Enterprise was not as refined as the radiator installation on the Campbell-Napier-Railton Blue Bird. The large, flat-faced, three-core radiator was covered in a fairing that stretched from the front of the car back to the engine cowling. In addition, the large wheel fairings constructed as water reservoirs had been installed behind the front wheels in place of the original, smaller fairings. The radiator added around 300 lb (136 kg) of weight and almost 2 ft (.61 m) of length, making the Enterprise approximately 7,000 lb (3,175 kg) and 27 ft 11 in (8.51 m) long.

Bad weather and poor conditions kept the Enterprise in its garage at Hukatere and off Ninety Mile Beach until 11 January 1932, when Smith made his first practice run. A speed of 125 mph (201 km/h) was achieved, and this was basically the first time the Enterprise was driven at any speed. Smith was satisfied with the shakedown run and prepared for an attempt on the 10-mile (16-km) record. The bad weather and poor conditions persisted, and it was not until 26 January that Smith felt the still-mediocre conditions were acceptable enough for an attempt. As the Enterprise ripped southeast on the beach, the wet sand literally sandblasted Smith and the car. At a speed around 228 mph (367 km/h), the car went out of control as it hit a patch of wet sand. Smith had to slow to 90 mph (145 km/h) before recovering, and then he pressed on to finish the run in 3:59.945 with an average speed of 150.034 mph (241 km/h). The toheroa shells on the beach had ripped up the special Dunlop slick tires during the run, and Smith decided to install the treaded road tires for the return run. The road tires were 36 in (914 mm) tall and 6 in (152 mm) wide. Because of the tires and conditions, Smith kept the Enterprise at a more sedate and even pace on the northwest run, completing the distance in 3:22.097 with an average of 178.132 mph (286 km/h). The average speed over both 10-mile (16-km) runs was 164.084 mph (264.077 km/h), breaking the previous record of 137.206 mph (220.811 km/h) set by Gwenda Stewart on 13 February 1930. Of course, Smith had hoped for and anticipated much more.

Smith sits in the cockpit before making a 10-mile (16-km) record attempt on Ninety Mile Beach. The Enterprise is equipped with the Dunlop slicks. Note the fuel filler cap behind the cockpit and the fabric covering of the tail fins distorted by the steel frame.

Smith was battered and bruised from the run; wet sand covered everything, including his goggles and the Enterprise’s windscreen. Better conditions were an absolute necessity before further attempts could be made and higher speeds attained. Curiously, various news outlets reported that Smith and the Enterprise made an LSR attempt on 27 January 1932, with 224.945 mph (362.014 km/h) on the first run and 199.285 mph (320.718 km/h) on the second. The speeds averaged to 211.115 mph (339.757 km/h), more than 34 mph (55 km) short of Campbell’s record. However, Smith, Harkness, and New Zealand and Australian newspapers deny that such an attempt was ever made. Where the erroneous report originated is not known.

After the run on 26 January 1932, Smith and the Enterprise took some time off. A new, smaller radiator was fitted because the previous radiator had worked a bit too well. The new radiator was only about 10% smaller and did not improve the Enterprise’s looks. Smith took the Enterprise out for a test run on 24 February and confirmed the new radiator was working well. That same day and half a world away, Campbell increased the 5-km (3.1-mi) record to 241.569 mph (388.768 km/h), the flying mile (1.6 km) record to 253.968 mph (408.722 km/h), and the flying kilometer (.6 mi) record to 251.340 mph (404.493 km/h).

The Enterprise running along Ninety Mile Beach with Dunlop road tires. With its radiator slightly out of frame, the car does not appear too odd.

Smith and the Enterprise made ready for future attempts at the 5-mile (8-km) and absolute speed records on 25 February 1932, but the weather did not cooperate, and tensions were brought to an all-time high. A disagreement at the hotel resulted in Smith and his party checking out and returning to Auckland; the Enterprise stayed in the garage at Hukatere. The party returned to a different hotel around 19 March, hoping for improved conditions and a smooth beach. However, some of the worst weather in 30 years continued to prevent any record attempts. More bad luck came in early April with legal proceedings filed against Smith by Harkness. Harkness, who was in Sydney, was absolutely furious when he saw the radiator modifications applied to the Enterprise. In addition, Smith’s constantly-delayed attempts on the record caused many to question his abilities, but most of these individuals were far from Ninety Mile Beach and did not have a grasp on its unsuitable condition.

In the meantime, on 26 February 1932, Campbell at Daytona Beach set new records for 5 km (3.1 km), 5 miles (8 km), and 10 km (6.2 mi). The respective speeds achieved in the Blue Bird were 247.941 mph (399.023 km/h), 242.751 mph (390.670 km/h), and 238.669 mph (384.101 km/h).

On 5 April 1932, Smith took the Enterprise on a brief drive along the unsuitable beach. The following day, Smith packed up the Enterprise and started the journey back to Auckland. While in Auckland, a new windscreen that revolved to clean itself of sand was installed. By the end of April, Smith and the Enterprise had returned to Hukatere, where the wait continued as rough weather made the conditions unacceptable for a record run. Because so many delays had occurred with the car’s arrival in New Zealand and with the record runs, detractors coined a new nickname: “Windy” Smith, implying he talked a lot about his plans but failed to come through. Locals had long since grown tired of the spectacle and inconvenience Smith’s record runs had caused.

This photo of Smith in the Enterprise, on what is most likely one of the 10-mile (16-km) runs, gives a good impression of the wet and less-than-ideal conditions on Ninety Mile Beach. The heavy rain created a couple of shallow streams that ran across the course, making it very unsuitable for a car traveling at high-speeds.

After all of the waiting and associated drama, Smith was ready to make another run in the Enterprise on 1 May 1932. Ninety Mile Beach was wet and still not in a good condition, but something had to be done, and Smith targeted the 5-mile (8-km) record. As the Enterprise traveled northwest on Ninety Mile Beach and accelerated through 170 mph (274 km/h) toward the start of the course, the Napier engine began backfiring and caught fire. Saltwater spray had inundated the engine compartment and caused arcing from the magnetos. The sparks ignited fuel around the Lion’s carburetors. Smith slowed as fast as he could and jumped from the car as it was still moving. The fire was quickly brought under control, and the Enterprise was returned to the garage at Hukatere. The damage was judged as not too severe, but Smith had spent a rough five months in New Zealand and was not interested in staying any longer.

Smith vowed to return the next year to go after the record, but he never did. Smith, his entourage, and the Enterprise returned to Sydney, and the car was tucked away in the garage of Smith’s friend Ted Poole. The cost of the record attempts began to set in as Harkness and others accused Smith of being either afraid to make a record attempt or incapable of driving at the speeds needed. Neither of the accusations were true. The truth was that pursuit of the LSR had cost Smith much of his savings, some of his dignity, and a few of his friendships. Eventually, Smith prevailed in a slander suit he brought against an Australian newspaper, but the rift with Harkness was never closed. In mid-1933, Smith talked about racing the Enterprise on Lake George, but plans for the site never came to fruition. Smith’s 10-mile (16-km) record stood until 6 September 1935, when George Eyston in Speed of the Wind achieved an average of 167.09 mph (268.91 km/h), 3 mph (5 km) faster than Smith, at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah. Later in life, Smith was happy to talk about his racing exploits, with the exception of the LSR attempts. Smith stored the Enterprise for a time, but the car was ultimately disassembled, and the Lion engine was sold for use in a speedboat. The Enterprise’s frame sat outside of Smith’s shop until at least 1958, the year Smith passed away, but no part of the car is known to exist.

The damage to the Enterprise after the Napier Lion caught fire during the 5-mile (8-km) attempt was fairly isolated. The coolant line to the radiator extended from the center of the cowling. The return lines ran outside of each frame rail.