Fur coats aren’t just a product of the modern industrial period, but now are seen to have a tradition stretching back some 300,000 years ago, albeit in a different setting altogether. People have been using bear skins as evidenced from a bear cave at the old Paleolithic site in Schöningen, Lower Saxony, Germany. No other documentation stretching back this far has been found anywhere in the world before! This site has previously yielded wooden hunting weapons along with the Schöningen mammalian skeletal assemblage.

Early Adaptation: Survival of the Warmest

“The find opens up a new perspective”, says University of Tübingen Professor Nicholas Conard, head of the Schöningen research project. “Animals were not only used for food, but their pelts were also essential for survival in the cold. The use of bear skins is likely a key adaptation of early humans to the climate in the north.”

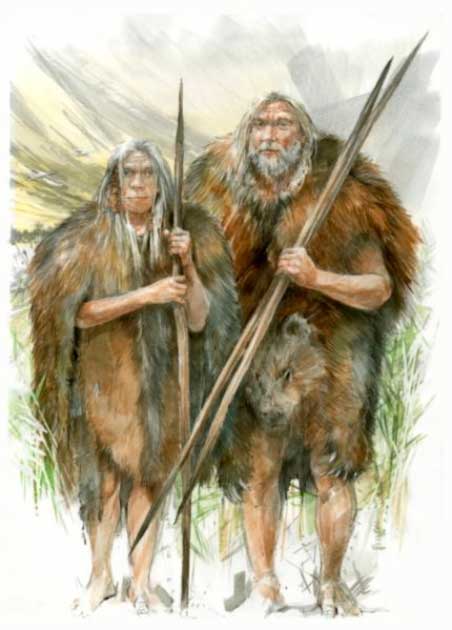

Homo heidelbergensis couple wearing cave bear skins to protect against cold. (Benoît Clarys/ University of Tübingen)

The study, published in The Journal of Human Evolution, studied cut marks on the hand and foot bones of cave bears. The Lower Paleolithic sites here have played a crucial role in the discussions around the origins of specialized hunting of large mammals as evidenced by wooden hunting weapons like throwing spears (9 in total), a thrusting lance, and throwing sticks (2 in number).

In addition to the aforementioned skeletal assemblage, clear indications of the exploitation of large herbivores can be gauged. As per a press release by University of Tübingen, these were for the purposes of meat, marrow, bones for tool production, and finally, skins.

Evidence of Bear Skinning: Across the Paleolithic

Another researcher, and lead author Ivo Verheijen, explained that the cut marks on bones are an indicator of utilization of meat. However, since there is literally no meat to be gained on the hand and foot bones (metatarsal and phalanx), such fine and precise cuts can be attributed to the careful removal of fur. This kind of skinning of bear bones has only been found in Boxgrove, United Kingdom, and Bilzingsleben (Germany).

Detail of the precise and fine incision marks on the metatarsal bones of a cave bear. (©Volker Minkus/ University of Tübingen)

Interestingly, the Eurasian Lower Paleolithic record shows no evidence for the exploitation of bear meat, reports Heritage Daily. Only Middle Paleolithic sites, like Biache-Saint Vaast in France, along with Taubach in Germany have displayed evidence for exploiting both skin and meat from bear carcasses.

This is one of the earliest examples in human history of active adaptation of early peoples (Homo heidelbergensis) to the climate in the north. What’s worth noting also is that bear skins must be promptly removed after the death of the animal, otherwise the hair and fur will be rendered unusable. Thus, the animals could not have been dead for too long at the point of skinning.

“The winter fur of a bear consists both of long top hair that forms an airy protective layer and short, thick hair that insulates particularly well. Bears, including the extinct cave bears, needed a strongly insulating fur for hibernation. These newly discovered cuts are an indication that people in Northern Europe were able to survive about 300,000 years ago in winter thanks to warm bear skins,” further explains Verheijen.

Just last year, a study from Morocco showed that even in a relatively warm climate, evidence of fur use and dozens of other tools for smoothing and polishing hides were found to produce fur. When the Homo sapiens of North Africa travelled to populate the corners of the globe, it appears that they likely did this having adapted to wearing animal skins and furs.

The Paleolithic sites in Schöningen and the ensuing investigation are a product of a collaboration between the University of Tübingen, and the Senckenberg Society for Natural Research. This long-term collaboration has been with the Lower Saxony State Office for the Preservation of Monuments. The project has been Lower Saxony Ministry of Science and Culture in Hanover.