Most college students preparing for the real world begin with an internship, part-time job, or creative pursuits. Harrison Duran digs up a 65-million-year-old dinosaur skull.

University of California, MercedThe fifth-year biology student has now formed a nonprofit with his colleague to find and preserve fossils like this while educating the public about the process.

The Badlands of North Dakota are no stranger to entombed prehistoric dinosaur fossils, as the region contains a trove of remnants from the Cretaceous period. According to CNN, the latest discovery is a 65-million-year-old partial Triceratops skull.

A fifth-year biology student from the University of California, Merced, Harrison Duran was on a dig when he encountered the prehistoric fossil. As a lifelong enthusiast of paleontology, the discovery was overwhelming.

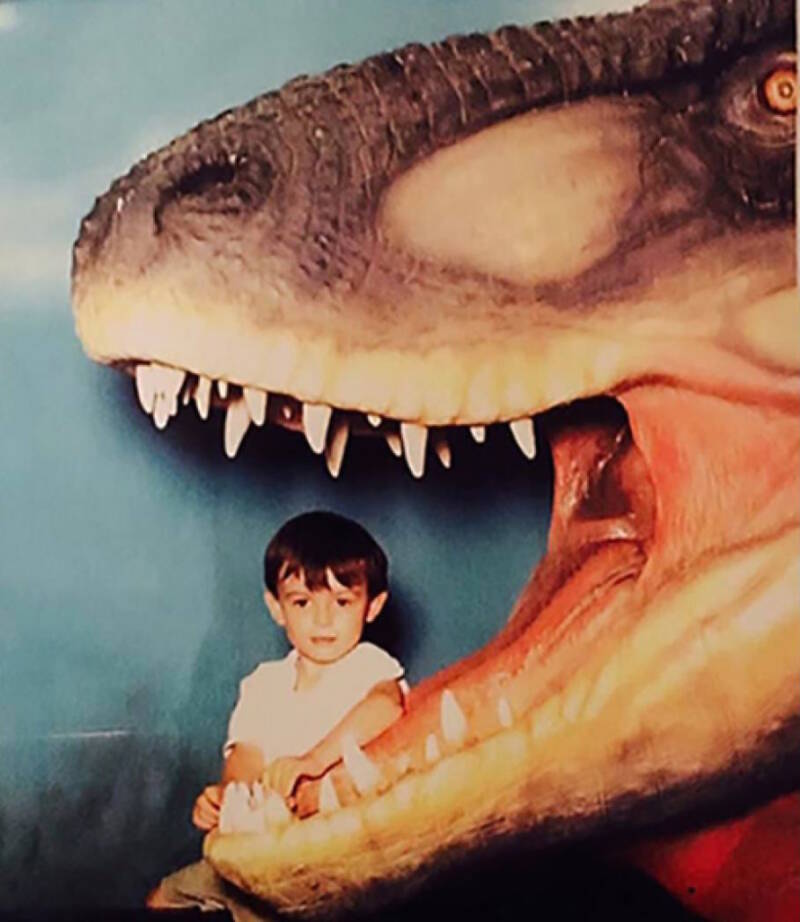

“I can’t quite express my excitement in that moment when we uncovered the skull,” said Duran. “I’ve been obsessed with dinosaurs since I was a kid, so it was a pretty big deal.”

The Hell Creek Formation is a rock bed configuration that spans Montana, Wyoming, and North and South Dakota, and has consistently yielded fossils from the late Cretaceous period. According to ThoughtCo, it was in this very formation that paleontologist Barnum Brown (named after circus showman P.T. Barnum and commonly referred to as “Mr. Bones”) found the remains of a Tyrannosaurus Rex in 1902.

Harrison Duran can know officially label himself a peer of Brown’s, as his discovery is just as remarkable.

Duran’s discovery wasn’t a sudden stroke of luck, either. Though he knew the history of the area and was accompanied by Michael Kjelland — a professional excavator and professor at Mayville State University in North Dakota — the pair was there for two weeks before they found the Triceratops skull.

Kjelland first met the ambitious young student at a conference, during which their shared passion for dinosaurs turned them into fast friends and partners.

Kjelland notably found another Triceratops skull last year near the current dig site. “I have been going out to the Badlands for years off and on, but to this particular site it was the first time,” Kjelland explained.

Under the sun of early June in the Badlands, the two started chiseling away. After four days of breaking apart rock and dirt to no avail, they actually found something. It wasn’t a sign of former life, but a fair amount of gold.

When they did encounter the fossil, it was upside down. Part of the animal’s left horn was exposed, with plant fossils that dated to the Cretaceous era surrounding the Triceratops skull.

“It is wonderful that we found fossilized wood and tree leaves right around, and even under, the skull,” said Duran. “It gives us a more complete picture of the environment at the time.”

University of California, MercedHarrison Duran has been a lifelong dinosaur fanatic, as evident by this photo of him as a young child. He told reporters his excitement at the find was “indescribable.”

Once the adrenaline rush and flurry of endorphins wore off, the two actually had to dig the specimen out of the ground. Before that grueling process began, they gave the dinosaur a name: Alice.

“It took a full week to excavate Alice, whose fragile skull was meticulously stabilized with a specialized glue to solidify the fractured, mineralized bones before an accelerant was applied to bond the structures,” the University of California, Merced, said in a statement.

Additional steps to ensure Alice would safely make her journey to the lab included coating her in foil and plaster. The fossil was then wrapped in a memory foam mattress before being placed in a box and shipped for further analysis.

Duran, meanwhile, is quite eager to return to campus with Alice in tow. It’s not every day that you can show off finding a 65-million-year-old dinosaur to your friends.

“It would be amazing for UC Merced to be able to display Alice on campus,” said Duran. “It’s such a rare opportunity to showcase something like this, and I’d like to share it with the campus community.”

University of California, MercedProfessor Michael Kjelland actually found a Triceratops skull near this latest dig site in 2018. He expects more bones to be uncovered in the area in the coming years.

As for the two successful paleontologists, Duran and Kjelland have founded a nonprofit called Fossil Excavators. The aptly named organization aims to locate and preserve fossils such as Alice and educate curious minds about the excavation process.

Fossil Excavators plans on conducting a wide swath of additional research on its latest discovery before putting in on display for people as passionate as Duran. As for the exact location of the dig site, paleontologists don’t really dig and tell.