In the mid-1930s, Hispano-Suiza developed the Type 86 engine specifically for use in railcars. A railcar is a self-propelled railroad coach meant to carry passengers or cargo on routes that are not profitable enough to operate a regular locomotive pulling non-powered railroad cars.

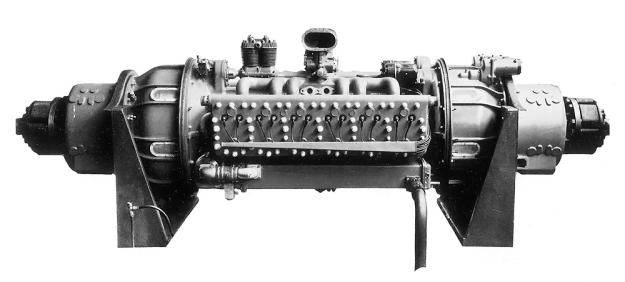

The Hispano-Suiza Type 86 railcar engine. From left to right across the top of the engine are the fuel pump, air compressor, carburetor (another on the opposite side), two magnetos with a speed governor, and two starters above the housing on the right. The oil cooler is positioned under the cylinder head.

Hispano-Suiza became involved in powering railcars with the adaptation of its six-cylinder automotive Type 56 engine of 487 cu in (8.0 L) and 46 hp (34 kW). In 1931, the V-12 Type 68 auto engine was bored out and modified for use in French “Micheline” (rubber-tired) railcars. This engine displaced 690 cu in (11.3 L) and produced 250 hp (186 kW). Unlike the previous Hispano-Suiza engines, the Type 86 engine was specifically designed for use in railcars.

The Type 86 was a horizontal (flat) 12-cylinder engine. The engine was designed to keep its height to a minimum so that it could be mounted transversely in place of one of the railcar’s bogies. The railcar’s drive wheels were connected by hydraulic couplings to gearboxes on both ends of the engine. This installation maximized the usable space in the railcar while lowering its center of gravity. Engine accessories, such as the compressor, carburetors, magnetos, and starters, were placed on top of the engine for ease of access and maintenance.

The two-piece aluminum crankcase for the Type 86 engine. Note the 14 long studs used to secure each cylinder bank to the engine.

With a 5.91 in (150 mm) bore and a 6.69 in (170 mm) stroke, the Type 86 displaced 2,200 cu in (36.05 L). The forged and hardened aluminum alloy flat top pistons had three compression rings and one scraper ring. Floating piston pins attached the pistons to tubular fork-and-blade connecting rods. The blade rod and its big-end cap meshed together through a tongue and grove design. Two tapered pins secured the blade rod around the crankshaft. The fork rod had a conventional big-end cap securing it around the crankshaft. Reportedly, these connecting rods and their bearings were the same as those used on some versions of the Hispano-Suiza 12Y V-12 aircraft engine. Although the Type 86 had the same bore and stroke as the 12Y, no other components were interchangeable.

The forged, chrome-nickel steel crankshaft was supported in the crankcase with seven main bearings and weighed 243 lb (110 kg). The single camshaft was positioned on top of the aluminum crankcase and was also supported by seven bearings. The camshaft was driven by the crankshaft via a helical spur gear at one end of the engine. This gear also drove the fuel pump and an air compressor for powering brakes and other accessories. At the other end of the engine, the camshaft drove two 12-cylinder magnetos and an engine speed governor.

The crankshaft and fork-and-blade connecting rods for the Type 86 engine. Note the blade rod with a tongue and groove design on the big end.

Each cylinder bank was attached to the crankcase by 14 long studs. Six open cylinder liners made of nitrided steel were installed in each aluminum cylinder bank. A single-piece, aluminum head (flathead) was attached to each cylinder bank by 50 bolts, in addition to the 14 long studs. The engine’s compression ratio was 5.85 to 1.

The intake and exhaust side valves were positioned parallel to and directly above the cylinder barrel. The valves opened into a small combustion space adjacent to the cylinder. The intake port and combustion chamber made the incoming air/fuel charge turbulent to allow for better mixing of gases. The chrome silicon valves were sodium-cooled and used three valve springs each. The valve seats were faced with Stellite for wear resistance. The valves were actuated by roller lifters. Two spark plugs were positioned in the cylinder head and directly above the valves. This position allowed the spark plugs to be easily accessed for maintenance.

At top is a complete cylinder bank assembly for the Type 86 engine. The middle image shows the same assembly as it would bolt on to the crankcase. At bottom is the flathead. Note the recessed space that formed the combustion chamber and allowed clearance for the side valves .

The Type 86 engine had pressure lubrication to all turning parts. Oil was drawn from the crankcase and sent though the engine via a pump located in the center of the crankcase. Two additional sump pumps drew oil from both ends of the crankcase. These pumps fed oil through oil coolers on both sides of the engine. The cooled oil was returned near the main pump in the crankcase.

A centrifugal water pump on each side of the engine drew cooling water from the radiator and through the oil cooler. After the water passed though the pump, it then flowed through the cylinder head and into the cylinder block via drilled passageways. The heated water would exit the top of the cylinder head via ports on both sides of the head and flow back to the radiator, positioned on the railcar.

Each side of the engine had one downdraft carburetor attached to an intake manifold located above the cylinder bank. Horizontal carburetors were proposed to reduce the engine’s height, but it is not known if they were ever used. The engine’s speed governor limited the engine to 2,500 rpm by regulating the butterflies of the carburetors. The exhaust manifold was also positioned above the cylinder bank, and its configuration varied depending on the engine’s installation.

The downdraft carburetor, manifold, and water pump (not to scale) used on the Type 86 engine.

For starting the engine, the Type 86 used two 24 volt electric starters with a maximum speed of 3,500 rpm. The starters were geared to the engine at a reduction of 37 to 1 so that they would turn the engine over at less than 95 rpm. Although one starter could start the engine when it was warm, the starters acted in unison, and both were needed to start the engine when cold, turning the engine at 80 rpm.

Internal splines in each end of the crankshaft received a coupler used to connect the engine to a gearbox. The couplers used hydraulic clutches, and one of the two couplers had a ring gear for starting the engine. The couplers were not mechanically locked at full load, which ensured smooth transmission of power to the gearboxes. Each gearbox used electromagnetic gear selection for its planetary gear reduction. At one engine revolution, the four gear reduction speeds were 0.237, 0.389, 0.610, and 1.0.

While not to scale, the camshaft, piston, and roller lifter for the Type 86 engine can be seen in the above image. Note the adjustment rod on the roller lifter to provide proper valve clearance.

With interruptions only for routine maintenance, the Type 86 was designed to provide continuous service for about a year, traveling 310–375 mi (500–600 km) per day. That service life worked out to around 125,000 mi (200,000 km) before an overhaul was scheduled. The power section of the engine was 58.1 in (1.475 m) long but grew to 122.4 in (3.109 m) with the couplers and gearboxes. The engine was 40.3 in (1.024 m) wide and 39.1 in (.993 m) tall. The Type 86 produced a continuous 550 hp (410 kW) at its normal operating speed of 2,000 rpm. But the engine could produce 650 hp (485 kW) at 2,000 rpm and 750 hp (560 kW) at 2,200 rpm.

A smaller engine called the Type 87 was also planned. This engine’s bore was reduced by 1.18 in (30 mm) to 4.72 in (120 mm). As a result, its total displacement was reduced by 792 cu in (12.98 L) to 1,408 cu in (23.07 L). It was believed this engine would develop 330 hp (246 kW). However, in the late 1930s, French industries were focused on rearming the French military, and few resources were available for other projects. Hispano-Suiza directed its attention to manufacturing aircraft engines, and development of the railcar engines was stopped.

Side and top view drawings of the Hispano-Suiza Type 86 engine.