Throughout history, schizophrenia has been difficult to define and even more challenging to treat. The lack of knowledge about the disorder has led to inhumane and sometimes violent treatment of those afflicted with it. In the United States and abroad, mental institutions were notorious for their neglect of patients, which was worsened by the fact that therapies for psychiatric illnesses were limited to ineffective lobotomies and insulin injections.

As World War II approached, people with schizophrenia became victims of an even greater human rights violation at the hands of the Third Reich. Between 1939 and 1945, an estimated 73 percent of Germans with schizophrenia were either killed or sterilized. At the end of the war, the treatment of schizophrenia started to inch toward a new horizon with the development of antipsychotic drugs in Europe and North America and activism geared toward protecting patients’ rights. But this shift away from institutions catalyzed issues in psychiatry that still affect people with schizophrenia to this day.

Defining and Treating Schizophrenia

According to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM V), the symptoms of schizophrenia are defined as delusions, hallucinations, flattened emotions, disorganized speech, and catatonia (a condition that causes either a severe lack of bodily movement or excessive, repetitive movements without external causes). The symptoms also tend to persist for at least six months. When 19th-century scientists were just beginning to define what we know today as schizophrenia, many of the same symptoms were observed, but the understanding of what schizophrenia was and how to treat it was markedly different.

Émil Kraepelin, a German psychiatrist in the 19th and early 20th centuries, developed a construct of what we now know as schizophrenia from disparate writings about catatonia, dementia, and hallucinations. Because Kraepelin linked the disorder with dementia, it became known as dementia praecox (“precocious madness”). Swiss researcher Paul Eugen Bleuler first used the term schizophrenia in 1908 at a conference in Berlin. From his clinical practice, however, he believed there was no relationship between dementia and schizophrenia and used the terms schizein to refer to “psychic splitting” — or a split from reality — and phren, a Greek word used to denote the spirit, mind, and soul.

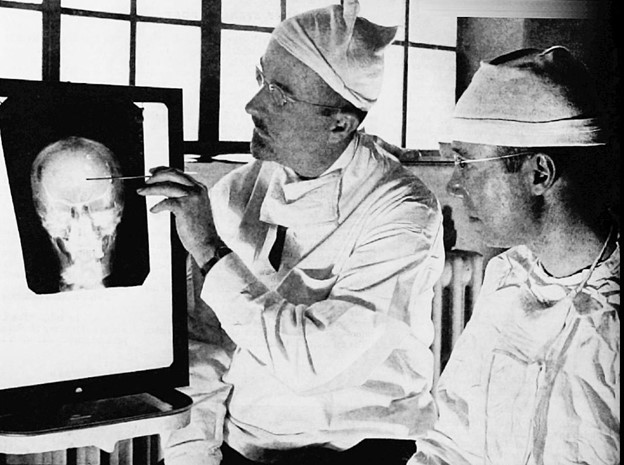

While experts created disparate theories about schizophrenia, the remedies proved mostly unhelpful. In the United States and Europe, doctors injected insulin into patients — a treatment method first offered in 1927 in Vienna by Polish scientist Manfred Sakel. The treatment ultimately put patients at risk of stroke and heart attack. Frontal lobotomies also became popular before and after World War II , but while the method pacified agitated patients, it also came with a high risk of further impairment.

Shock therapy was introduced not long after. A Hungarian neurologist named László Meduna brought chemical shock therapy to schizophrenic patients beginning in the early 1930s. This technique resulted in temporary remission for some of his patients, jolting them out of their catatonia — but the effects were short-lived. Even with questionable results, Meduna added the treatment to the medical literature, which encouraged the continued and widespread use of chemical shock therapy.

Because of the side effects associated with chemical shock and insulin, Italian scientists in 1938 invented electroshock therapy, but it resulted in a similar issue of temporary lucidity followed by relapse. As a result, psychiatric hospitals served as storage spaces rather than true treatment centers.

While conditions in the United States were troubling, Germany’s way of dealing with the mentally ill became infamous. Even before Hitler’s reign, the concept of racial hygiene proliferated in Germany as early as the turn of the century. Beginning in the 1930s, however, the German Chancellery would invest in research that would write one of the most disturbing chapters in psychiatric history.

Schizophrenia and the Third Reich

In the late 19th century, ideas about eugenics were budding in Germany. Alfred Ploetz, a physician who was active at the turn of the century until his death in 1940, coined the term “racial hygiene” and founded the German Society for Racial Hygiene in 1905. The organization received government support for a time but ultimately dissolved after World War I.

Ploetz’s colleague and brother-in-law, psychiatrist Ernst Rüdin, shared some of his interests. Rüdin developed a special focus on schizophrenia going back to 1916 with his first publication on the genetics of the disorder. He applied the theories of Gregor Mendel — the man credited as the father of genetics — and the year after its publication, Rüdin led the genealogical-demographic department of the German Institute for Psychiatric Research in Munich. Although the institute was not overtly eugenicist, by the start of Hitler’s reign in 1933, new political overtones in the institute were palpable. The director of the department of neuropathology, Walther Spielmeyer, lamented that the “present atmosphere is not conducive to the peace of mind necessary for objective research.”

Rüdin’s colleague, Hans Luxenburger, was also interested in the genetics of schizophrenia and was widely known for using twins in his research. But after the “Law for the Prevention of Genetically Diseased Offspring” that allowed coerced sterilization of those deemed unfit for procreation by a special court went into effect on July 14, 1933, Luxenburger attempted to write a paper decrying sterilization. Dissenters like Luxenburger, however, were quickly suppressed by Rüdin, who was under the orders of the Nazi Health Minister. In letters to a fellow researcher, a frustrated Luxenburger acknowledged that he “would be hanged” if he claimed schizophrenics should be able to have families.

Some researchers managed to escape the Third Reich, including Heinz Lehmann, who would later become important in treating schizophrenia. Born in 1911 in Berlin to a Jewish physician, Lehmann in 1937 obtained permission from the Gestapo to leave Germany for a two-week vacation in Quebec. Once there, he remained in the country as a refugee.

Many who stayed in Germany helped implement the sterilization plans. A colleague of Rüdin’s, Franz Kallmann, said in a 1935 speech that he believed schizophrenia was passed down through a recessive gene and advocated for examining all carriers within a family, whose schizophrenic gene could be discovered by spotting “minor anomalies.” If these “minor anomalies” appeared, sterilization would inevitably follow.

Yet the plan for eradicating mental illness did not stop at sterilization. On September 1, 1939 — the day Germany invaded Poland — Hitler penned a letter that authorized the killing of psychiatric patients. The program was known as T-4, or Tiergartenstrasse 4, which was the Berlin address where the operation was administered. The first method of mass murder was carbon monoxide showers, which were used to kill over 70,000 mentally and physically disabled patients by August 1941.

Whether by starvation, toxic gas, or lethal injection, high numbers of psychiatric patients across the Third Reich, including men, women, and children, were victims of extermination. Since the ability to work was a factor in the T-4 program, it’s believed that schizophrenia was targeted more than any other mental disorder.

American Institutionalization

Most institutions before and during the war are remembered for their neglect and abuse. Some institutions were seen as humane sanctuaries; nevertheless, the respite they offered came with the risk of making even recovered patients unable to cope with the outside world, thus making their stay at the facilities permanent.

Adding to the horrors of some mental institutions was eugenics. Even in the United States, eugenics had its adherents, despite the practices of Nazi Germany becoming known in America in the 1930s. Influenced partly by the economic crisis of the Great Depression, sterilization of mental patients, especially in California, was not uncommon. In California, about 20,000 patients were sterilized between 1919 and 1952. Economic strain inspired this practice and also caused staff shortages, underfunding, and overcrowding. World War II only worsened these financial and staffing issues.

In 1942, Warren Sawyer, a Quaker and one of 37,000 conscientious objectors who were exempt from combat in World War II because of religious beliefs, entered Civilian Public Service at Philadelphia State Hospital at Byberry. Sawyer found himself alone when he began his work: Many of the medical staff had been drafted. With limited supplies and help, Sawyer gazed upon 40 bed patients during his night shift, many of whom were lying in their own urine and excrement. Making conditions worse, the hospital did not have enough bed sheets or even powder to relieve their bedsores.

Even though he’d worked at a hospital in the past, this was the first time the 23-year-old had to pack bodies and roll them to the autopsy room. The overcrowding, neglect, and outbreaks of violence at Byberry became notorious over the years, and Sawyer and other conscientious objectors were instrumental in exposing it. Sawyer’s colleague, a fellow Quaker named Charlie Lord, took photographs of the facility that were published in Life magazine in May 1946. The photos of the abused patients, reminiscent of Nazi concentration camps, had a powerful impact and sparked a national public outcry.

Among these patients, psychiatric disorders featured prominently, according to a 1925 census of Byberry. Whether related to manic depression (now known as bipolar disorder), alcoholism, or dementia praecox (schizophrenia), people suffering from psychosis swarmed the filthy infirmary.

By the time of the Civil Rights Movement, Sawyer and other activists addressed the inhumane treatment of patients in mental hospitals. The 1963 Community Mental Health Construction Act granted money to states for community mental health facilities. In 1966, the case of Lake v. Cameron introduced the idea that the patient should, whenever possible, be discharged to the “least restrictive setting.”

Post-War Drugs and Deinstitutionalization

The development of antipsychotics revolutionized the treatment of schizophrenia, replacing less effective drug therapies like insulin injections. As the name “antipsychotic” implies, the drugs control the symptoms of psychosis, including hallucinations, catatonia, and violent mood swings. The first medication, chlorpromazine (brand-name Thorazine), did not hit the market until the early 1950s; prior to then, it was developed as an antihistamine that turned into an anesthetic and then finally a treatment for schizophrenia.

French surgeon Henri Laborit was stationed at Bizerte Naval Hospital at Sidi Abdallah, Morocco, when he observed patients dying from shock during surgery. From this experience, he developed an interest in increasing the safety of surgery. After the Allies liberated the area in 1943, the hospital saw growth in medical specialties, enabling Laborit to experiment with new treatments by the late 1940s. Both he and French chemist Paul Charpentier were interested in improving the safety of surgery, and Laborit theorized that he could shut down a patient’s stress response with an additional anesthetic.

Charpentier synthesized chlorpromazine in 1951 as an antihistamine, but in noting its potential as an anesthetic, he gave the drug to Laborit to see if patients would remain asleep longer during surgery. When Laborit saw that chlorpromazine had a calming effect on patients, he began experimenting: Using the drug on a psychotic patient, he found it reduced agitation after less than a month of treatment.

In Montreal, Heinz Lehmann caught wind of the research on chlorpromazine and quickly obtained it for his own practice. He co-wrote a paper with his colleague H.E. Hanrahan in which he coined the term “antipsychotic.” Once its efficacy for schizophrenia was proved, the drug went into widespread use.

A second generation of antipsychotics emerged during the 1960s and 1970s, adding to the expanding cabinet of treatments. In 1965, German scientists in Mannheim studied the growth of new cases of schizophrenia, the first postwar study conducted in the country. This rise in cases underscored the need for continued research into drug therapies.

Clinicians in Germany ran successful trials on a new type of antipsychotic called clozapine. The drug, which is still used today, works by lowering dopamine levels in certain parts of the brain. Although dopamine is normally considered a feel-good chemical, researchers found that it was overactive in the brains of people with schizophrenia. Ultimately, the same chemical that could cause heightened pleasure or creativity could in excess lead to hallucinations.

Clozapine and other dopamine-inhibiting drugs were game changers in the treatment of schizophrenia, helping to bring lobotomies to an end in the late 1960s and reducing dependence on institutions. But the closure of institutions over the coming decades had unexpected consequences, putting many people with mental health issues on the streets after brief hospital stays.

Autism specialist Darold Treffert denounced the consequences of deinstitutionalization in the early 1970s, calling it “dying with one’s rights on.” Indeed, patients on the streets became more vulnerable to narcotics use, arrest, violence, and suicide. Although antipsychotics stabilized many patients and afforded them more independence, severe cases fell through the cracks as people with schizophrenia struggled to faithfully take medications, sometimes due to unpleasant side effects or paranoia.

Decades later, schizophrenia remains one of the most stigmatized mental health conditions, but positive effects were seen in the aftermath of World War II. Over 3,000 conscientious objectors worked in mental hospitals, and a handful confronted and exposed the deplorable conditions, helping to show the public the human rights issues with institutions.

Dr. Steven Taylor, author of Acts of Conscience: World War II, Mental Institutions and Religious Objectors, stated that in the postwar climate, “America’s confidence was soaring. . . . We were morally superior; we were militarily superior,” but the mental health situation reminded people that “America had its shortcomings.” In the aftermath of deinstitutionalization, there are still salient shortcomings, but decades of research and activism in the postwar era laid the groundwork for further discussion about human rights and mental health.