During a time when slavery had been abolished in most of the world, human zoos remained a popular attraction for millions of Europeans and Americans.

They flocked to exhibits showing groups of dark-skinned people from Africa, Asia, and North America surrounded by trappings that were supposed to represent their “natural environment.”

Most of these cruel and inhumane exhibits closed down in the wake of World War I, but their legacy continues to add to the long stain that is the history of racial exploitation.

The Origins of Human Zoos

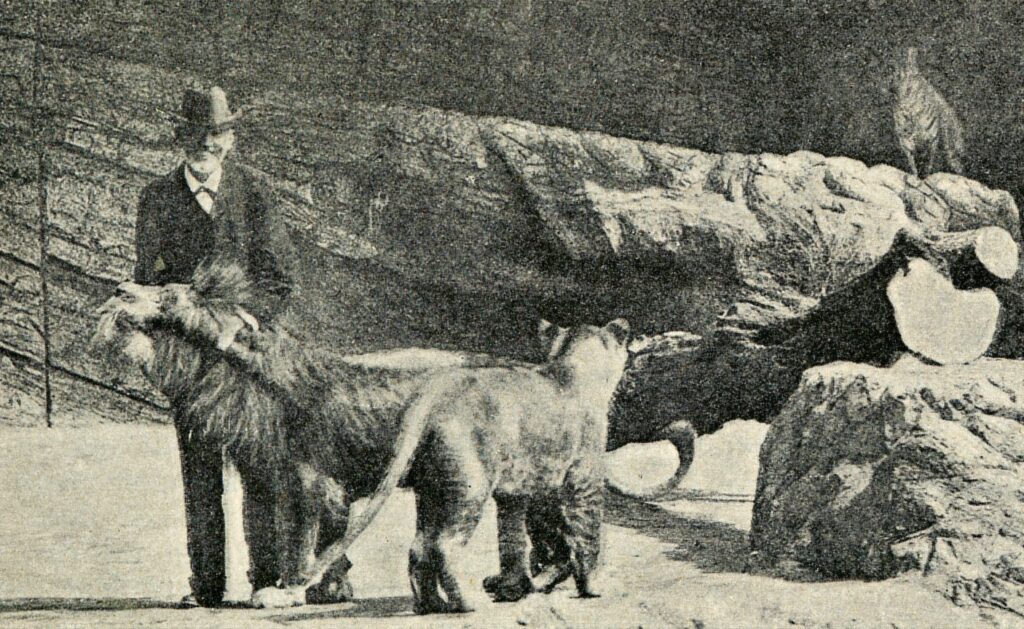

The first human zoos were opened in 1874 by an exotic animal trader named Carl Hagenbeck. For years, Hagenbeck had displayed animals from far-flung regions of the world in his traveling shows as a way to introduce regular people to exotic wildlife.

This was at the height of the industrial revolution. People in European countries such as Britain and Germany finally had enough spending money and leisure time to go out and pursue entertainment. This made Hagenbek’s shows highly popular.

But Carl Hagenbeck wasn’t satisfied with his success with exotic animals and decided to take it a step further. He thought to himself, “Why not show not only animals but humans too?”

To the deeply entrenched racist hierarchy that Hagenbeck and others held at the time, Africans were just a couple of rungs above animals on the hierarchy of humanity. A show full of humans would be like his previous show but even more exhilarating.

Carl Hagenbeck was not the first European to exploit foreign cultures and peoples by putting them on display. For centuries, European explorers would take native people who they found in the New World or Africa back with them to Europe to show to their monarchs.

What Carl Hagenbeck did was take the old practice of kidnapping and exploitation and turn it into a profitable industry.

Human Zoos and Colonialism

Today, most people have probably never heard of human zoos. But 150 years ago, Europe experienced what could be called a human zoo craze.

During the early 1900s in Germany, “People’s Shows” attracted large gatherings of spectators. They were interested in getting a glimpse of the exotic without having to travel.

And it wasn’t just Germany. In pretty much any large city in Europe, human zoos found a ready audience.

In the United States, cities from Philadelphia to San Francisco to New York had human exhibits that were all very popular – not to mention profitable. In 1896, the Cincinnati Zoo held an exhibit of Sioux Indians that made them $25,000 in three months.

But by far the largest gatherings of spectators occurred at the World’s Fairs. In Paris in 1889, 28 million people passed through the exhibits, one of which was a group of 400 indigenous people.

Unfortunately, the inclusion of indigenous people in World’s Fairs was something that would be repeated again and again. Even as late as 1958, with the World’s Fair in Belgium, millions of people could still come and gawk at exhibits filled with people from “exotic” races.

Belgium was one of the countries where human zoos flourished most. During King Leopold’s nearly 50-year reign from 1865 to 1909, thousands of people from Congo, a Belgian colony at the time, were taken back to Belgium as propaganda tools for the king’s empire-building project.

By exhibiting Congolese people, King Leopold hoped to spark interest in his Belgian colony and gain more support from the public. All the while obscuring the atrocities being committed under his colonial system.

Growing Up in a Human Zoo

Europeans may have loved the idea of human zoos. But for the people who were forced to work in them, the experience was incredibly degrading – not to mention dangerous.

Take Theodor Wonja Michael for example. During his extraordinary life, Theodor was an actor during the Nazi era, a survivor of a concentration camp, and worked as a spy during the Cold War.

But as a child, he was forced to work in an exhibit in which he was dressed in a raffia skirt and pretended to be a “wild” African boy. His father had immigrated from Cameroon and the only decent-paying job he could find was in a human zoo.

When Theodor was just one year old, his mother died. The courts decided that his father was not capable of caring for his four children. The family was then broken apart, with each child going to a different human zoo operator.

For Theodor, it was devastating. Not only had he been forcibly separated from his family, he found himself completely dependent on the whims of his operator.

Human zoos were a terribly oppressive environment. People pushed up against the barriers separating them from the exhibitions. They jeered and heckled the performers. And they didn’t hesitate in showing their displeasure when they didn’t get what they wanted.

In November 1881, at an exhibit in Berlin, a massive mob of visitors was denied the opportunity to see a group of indigenous people who had decided to hide in their hut.

Enraged, the crowd pressed up against the enclosure and destroyed fences and other barriers in their attempt to interact with the subjects of the exhibit. For the people trapped inside the exhibit, the reaction of the crowd must have been terrifying.

Indeed, many indigenous people, having been lured to Europe with false promises, realized too late the grave mistake they had made in believing the profit-hungry entrepreneurs.

One group of eight Inuit who were placed in an exhibit in Berlin. They complained, “The air is constantly buzzing from the sound of the walking and driving; our enclosure is filled up immediately.”

This particular group of eight Inuit suffered for just a few months before dying one by one from smallpox.

The End of Human Zoos

Human zoos may seem like a relic of the past, but the age of racial exploitation has never really ended.

Many human zoos closed down after World War I. This was partly because the survivors began integrating into society and could no longer be forced into such miserable working conditions.

But subsequent World’s Fairs and zoos continued to include humans as part of their exhibits for decades.

In 1958, the Brussels World’s Fair featured a Congolese village where men and women were made to dress in traditional garb and carry out crafts in front of hordes of onlookers. If the visitors weren’t happy with the “villagers’” performance, they would shout and throw bananas or money at them.

Even as recently as 2005 in Augsburg, Germany, a celebration of African culture known as the “African Village” festival was held, of all places, in the center of the city’s zoo.

Although the event’s organizer saw nothing wrong with holding the festival next to monkey cages and a Savannah exhibit, many others understandably took offense. Some people were so upset that they even threatened to burn the zoo down.

While the days of forcing humans into cages for public entertainment may have ended, it is clear that the history of human zoos has left a deep scar that may never fully heal.

If there is one silver lining in this tragic history, it is that it serves as a reminder that one person’s entertainment is another’s exploitation, no matter how well-intentioned you may be.