“I Don’t Want to Talk About It” was only six years old when it reached number one in the UK singles chart, yet already it felt like a song from a lifetime before — which was precisely why it reached number one. The song had been written by Danny Whitten, who recorded it as the closing track on the first side of the debut album by his group Crazy Horse in 1971, but it was Rod Stewart who made it a hit.

Through the first half of the 1970s, across the albums he made for Mercury Records, Stewart had been one of the great interpreters of the songs of others, creating a distinctly British hybrid of soul, folk and rock’n’roll. In 1975, though, hede camped to Warner and to the US to record his Atlantic Crossing album. If this was, in retrospect, the start of his artistic decline, then that first Warner album still offered proof of his gifts.

“I Don’t Want to Talk About It” was a perfect song for Stewart. Crazy Horse’s original — as you might expect from a band best known for backing Neil Young — was a song that sounded less as though it had been written than drawn from a deep well of American music: mournful, with slide guitar weeping throughout. It had a lachrymosity that teetered on the verge of parodic — “If I stand all alone, will the shadow hide the colour of my heart / Blue for the tears, black for the night’s fears” — but never quite teetered over, because Whitten’s agony was wholly believable.

Crazy Horse’s version would have fitted easily on to Every Picture Tells a Story, Stewart’s own 1971 album. By the time of Atlantic Crossing, Stewart was softening his sound, and the album — played by the cream of American session musicians — was rather lusher than the records that made his name. His reading of “I Don’t Want to Talk About It” was delicate and filigreed, and — eventually — just a little gloopier than it needed to be, once the strings entered

a couple of minutes in. But his voice, raspy and ragged and heartbroken, was a thing of wonder.Stewart’s version was just an album track, but after its release, he and his label noticed that it had become a crowd favourite, a chance for thousands of voices to commune with melancholy. And so it was released as a single in 1977 (as a double A-side with “The First Cut Is the Deepest”), despite the fact that Stewart had released another album, A Night on the Town, in the meantime. It would always have been a hit — Stewart was at the height of his commercial powers — but it might not have reached number one without the intervention of punk rock.

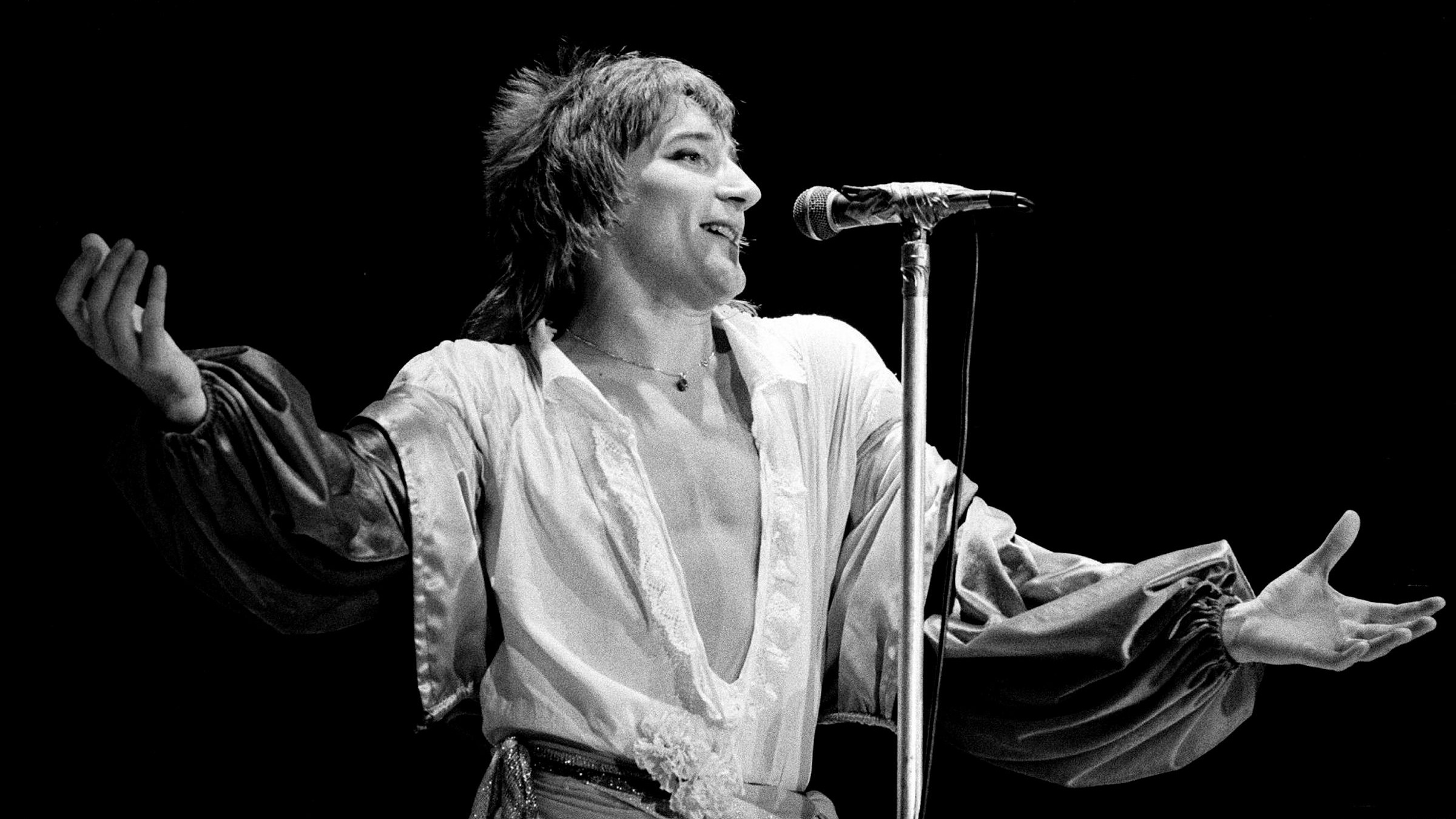

Stewart was fighting it out for the top spot in the UK charts with The Sex Pistols, whose single “God Save the Queen” looked as if it might be a spoiler for the silver jubilee celebrations of Queen Elizabeth II in the early summer of 1977. And so, longstanding rock legend holds, the charts were rigged, and Stewart was beckoned to number one, with The Pistols stalled at number two (an achievement in itself, given that “God Save the Queen” was not played on the radio, and many stores refused to stock it). The contrast between Stewart — a feather-cutted peacock, squire to blondes, epitome of the rock aristocracy — and The Pistols, the amphetamine-addled guttersnipes whose mission was to “get pissed, destroy”, was a generational contrast for the ages, even if Stewart was only 32.

But “I Don’t Want to Talk About It” is a song of such indelible beauty that even those who had grown up on The Pistols’ side of the war adored it. Everything But the Girl,

for example. The group’s singer, Tracey Thorn, had been a punk, and her first band, Marine Girls, became indie heroines, but she had grown up in a home where Rod was appreciated unambiguously and unironically. And so EBTG covered it beautifully and sensitively, reaching number three, and found that they suddenly had an audience who did not share their background in alternative music.

for example, playing it straight, fares better than the folk duo Indigo Girls, who fiddle with the arrangement too much. Dina Carroll, though, treated it like a jazz standard, with surprisingly good results. But, like all standards, it attracts those who should leave it very much alone — the comedian Freddie Starr, for example, whose version is both vocally overwrought and musically horrible, the soundtrack to a wine bar that for some reason sells only cheap lager.Danny Whitten never got to see his song become universal. One reason his agony was so believable was that he was addicted to heroin, to alleviate his rheumatoid arthritis. He tried to quit, but only by adopting other addictions. Within 18 months of that first Crazy Horse album being released, he was dead. His life was short, but his song lives forever.