A couple of years ago, a study alluded to Neolithic farmers in Chile’s Atacama Desert engaging in violent battles over resources. Turn back the clock further, and a newer study points to ancient hunter-gatherers from the same region engaging in brutal interpersonal violence on a consistent basis. This evidence has been gleaned from researching skeletons, weaponry, and rock art from around 10,000 years ago, to ascertain that violence was a “consistent part of the lives of these ancient populations for many”.

Using a multifaceted methodology encompassing bio-archaeology, geoarchaeology, and socio-cultural investigations, a team led by Vivien Standen from the University of Tarapacá in Chile uncovered the harsh realities experienced by ancient human populations. This research has been published in the latest edition of the journal PLOS One. Incidentally, Standen also spearheaded the 2021 research on Neolithic violence in the Atacama.

Assessing the Violence in the Atacama Desert: Lethal and Non-Lethal Infliction of Pain

The research involved an in-depth examination of 288 adult remains spanning a time frame from 10,000 years ago to 1450 AD, with a particular focus on identifying physical indicators of interpersonal violence. Concurrently, the team conducted strontium isotope analyses (strontium isotope ratio in bones reflects the environment and dietary intake, helping define a person’s geographical origins) to determine whether these individuals belonged to local or non-local communities.

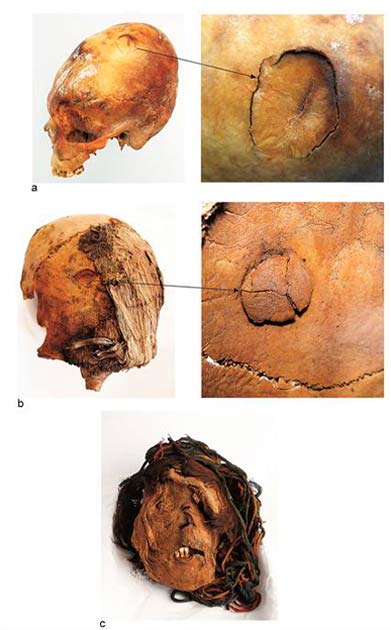

Some bodies still had soft tissue, preserved as a result of the arid desert environment, offering insight into injuries that would have otherwise been unknown. The bizarre nature and brutality of violence included the skin of a woman’s chin being stretched to cover her mouth, while her upper lips were dragged across her nostrils.

Perimortem cranium fractures, Formative Period. (Standen et al., 2023, PLOS ONE/CC-BY 4.0)

“Traces of lethal and non-lethal violence on bones and soft tissues, the use of weapons, and rock art representations, support the notion that populations faced conflicts and tensions that, sometimes, were resolved by violent mean. The chemical signature of Sr for individuals sampled suggests that these fights and brawls were generated in the context of local groups, [as opposed to outsiders]” they write in the paper.

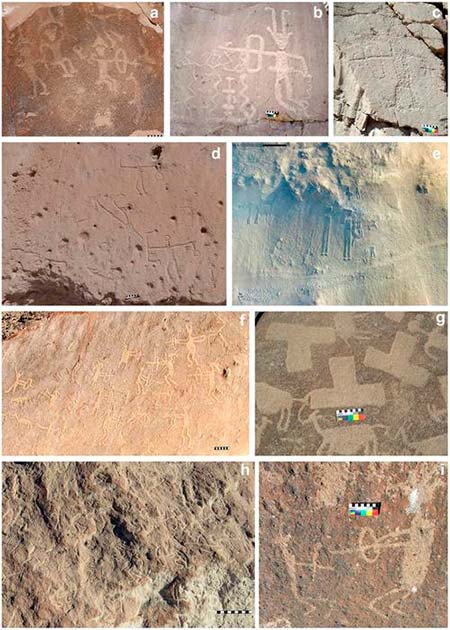

At the same time, the team delved into the analysis of weaponry and the representation of combat in rock art, yielding the revelation that “violence remained a constant throughout the 10,000-year period during which these societies existed in isolation from the Western world.”

It was noted that the overall prevalence of brutality remained fairly consistent across different time periods, but the nature of violent acts exhibited variation. One key observation was the upsurge in lethal violence during the Formative Period (1000 BC–500 AD), a trend mirrored in other research conducted in the Andean region. Conversely, non-lethal forms of violence experienced a slight decline over time, notes a press release.

Going to War: A Host of Reasons

“Despite all the technological advances, humanity has not learned to resolve its conflicts in a different way than our millenary ancestors, in peace and without war,” note the authors.

In an attempt to elucidate the underlying reasons for this penchant for violence, the researchers postulate that the absence of centralized political structures within hunter-gatherer communities could have contributed to heightened tension. This acquires greater interest and significance, especially given the organization of these populations into smaller, decentralized groups.

Motifs of warfare in rock art and geoglyphs from the Formative Period (a-c) and Late Intermediate Period in the Atacama Desert. ( Standen et al., 2023, PLoS ONE)

Another more obvious reason suggested that violence could have arisen due to competition for resources in the harsh desert environment. This factor might have intensified as agriculture gained prominence and became more widespread. The 2021 study had shown that violence increased with the emergence of horticulture, leading to a greater concentration of individuals.

The authors note that “…finally, from the Formative Period onward, we cannot rule out a certain level of conflict between fishers and their close neighbors, the horticulturalists.”

After all, hunter-gatherers were human societies that relied solely on foraging and hunting for sustenance. This way of life was prevalent among all humans until approximately 12,000 years ago, with most communities typically leading a nomadic existence, reports IFL Science.

Another feature of hunter-gatherer societies was that human beings, transitioning from small clans or ‘bands’ of 25, constantly on the move for survival, now began to settle down. With settling down, globally populations expanded plentifully, leading to increased competition over resources, a pattern that is seen in modern day societies too.