On November 24, 1971, a man known as D.B. Cooper hijacked a plane headed from Portland to Seattle, collected an enormous ransom, and then simply vanished into thin air.

Fifty years ago, a mystery man known as Dan Cooper, a.k.a. D.B. Cooper, pulled off one of the most jaw-dropping heists in recorded history. Over the course of a few hours on November 24, 1971, he hijacked a plane, stole $200,000, and then escaped via parachute — never to be seen again.

It all happened aboard a Boeing 727, Northwest Orient Flight 305 from Portland to Seattle. It was supposed to be a quick, straightforward trip — and D.B. Cooper initially looked like a regular business traveler. But it soon became clear that that was not the case.

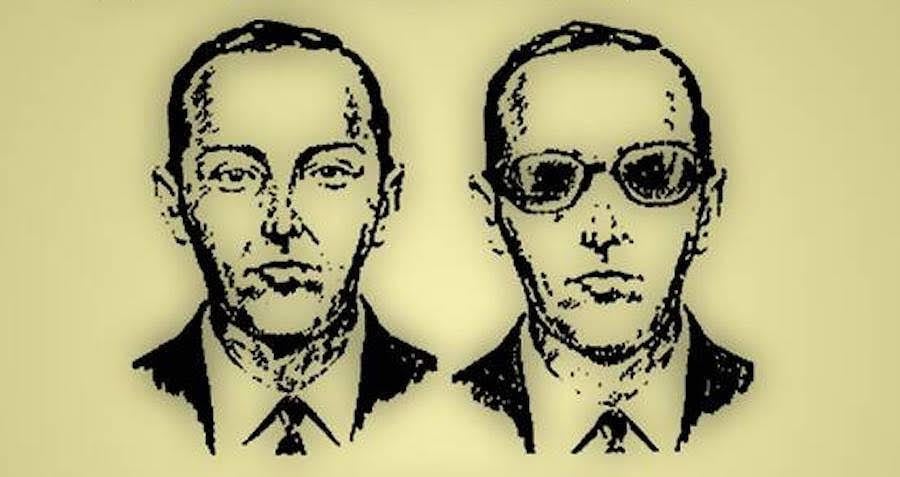

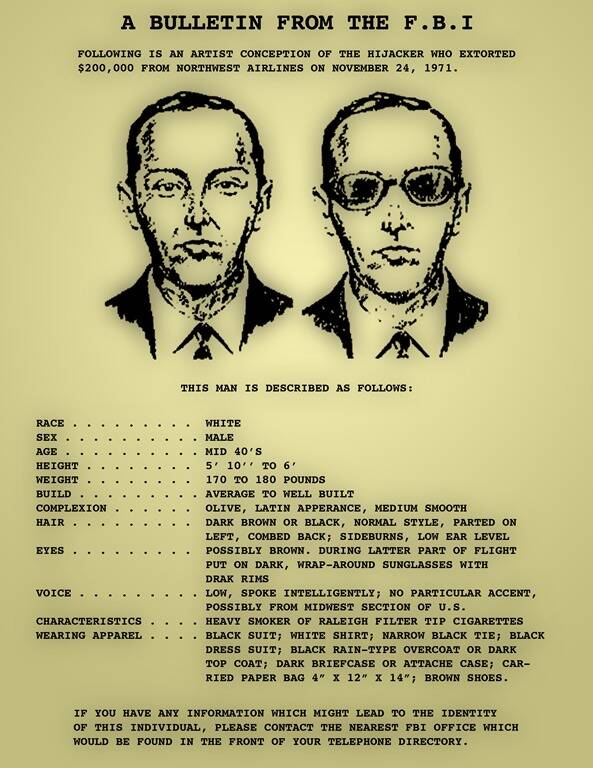

Federal Bureau of InvestigationThe FBI sketch of D.B. Cooper, shown in black and white and in color.

To this day, investigators are stumped as to who D.B. Cooper was, how he executed the heist, and how he made his escape.

Although they have a clear physical description of the man and a DNA sample, many crucial questions remain unanswered: Where is D.B. Cooper? Who is D.B. Cooper? And did he even survive his fall?

How “Dan Cooper” Initiated His Hijacking

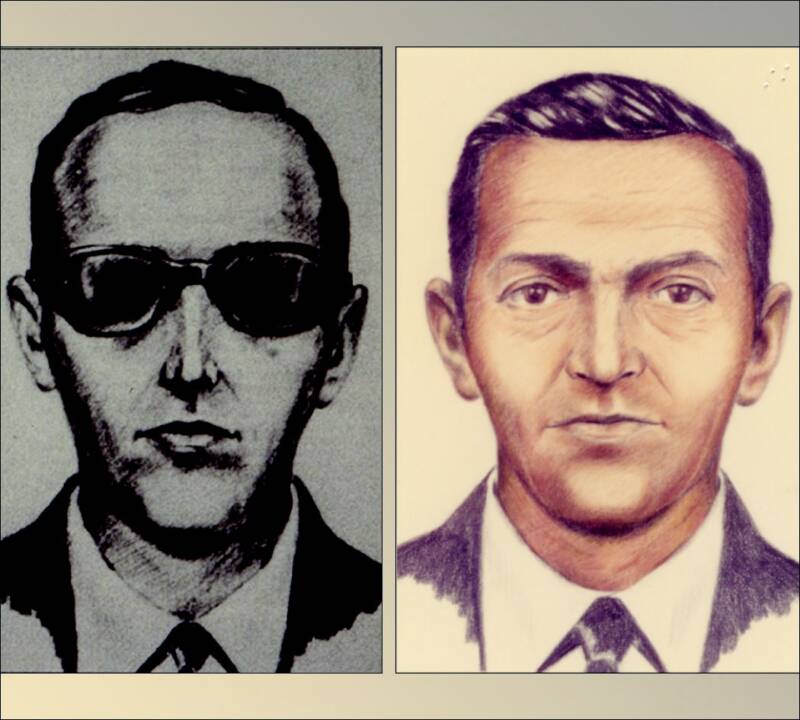

Wikimedia CommonsThe wanted poster for D.B. Cooper, which describes his seemingly ordinary appearance.

On November 24, 1971, a man who called himself Dan Cooper bought a one-way plane ticket from Portland to Seattle. He boarded Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 305 and settled into seat 18C. This trip normally took about 30 minutes, and nothing suggested that the flight would be anything but typical.

At first, “Dan Cooper” seemed like a normal passenger. His black tie and white shirt suggested that he was a business traveler, an impression reinforced by his briefcase. Like many airline passengers of the era, Cooper quickly lit a cigarette and ordered a drink — bourbon and soda — which he drank quietly as the plane took off.

Listen above to the History Uncovered podcast, episode 15: DB Cooper, also available on iTunes and Spotify.

His appearance was unremarkable — and his FBI file later reflected that. “White male, 6’1″ tall, 170-175 pounds, age-mid-forties,” it notes dryly. “Olive complexion, brown eyes, black hair, conventional cut, parted on left.”

But then Cooper flagged down a stewardess — the old term for a flight attendant — named Florence Schaffner. He handed her a piece of paper. Schaffner was used to businessmen flirting with her, so she assumed the note was just a phone number and slipped it into her pocket. Cooper leaned forward. “Miss,” he said. “You’d better look at that note. I have a bomb.”

Schaffner opened the note. A chilling statement was written in felt pen, all in capital letters: “I have a bomb in my briefcase. I want you to sit next to me.” Schaffner sank into the seat next to Cooper and asked to see the bomb. Calmly, Cooper opened the briefcase. Inside, the stewardess could see a tangle of wires, a battery, and red-colored sticks that looked like dynamite.

“I want $200,000 by 5:00 p.m.,” Cooper said calmly. “In cash. Put in a knapsack. I want two back parachutes and two front parachutes. When we land, I want a fuel truck ready to refuel. No funny stuff or I’ll do the job.”

Schaffner went to tell the pilot. Meanwhile, the other passengers remained oblivious to the danger that was brewing in seat 18C. Bill Mitchell, a University of Oregon sophomore, was sitting across the aisle from Cooper. He recalled that the pilot announced something about engine trouble. They would have to circle for a bit, letting off some fuel.

The pilot invited passengers to move toward the front of the plane, but Mitchell stayed in his seat — completely unaware of the situation that was unfolding. He later confessed that he actually felt jealous that the stewardess was giving Cooper so much attention.

“My ego got in the way of this,” Mitchell said in 2019. “It sort of bugged me that this flight attendant was talking with this older guy with a suit and smoking, and here you had a University of Oregon sophomore sitting right across the aisle and she wouldn’t make any eye contact or anything.”

Mitchell may have been unaware of the man’s sinister plan, but he was able to describe his appearance after the flight. Once the FBI launched their investigation, Mitchell and the flight attendants helped with the sketch of the suspect. No other passengers had gotten a good look.

How D.B. Cooper Made His Daring Escape

Wikimedia CommonsA Northwest Orient Airlines plane of the same model that Cooper hijacked.

As the plane circled in the air for about two hours, officials on the ground scrambled to satisfy D.B. Cooper’s demands. The plane landed in Seattle at 5:39 p.m. Around that time, the airline staff approached Cooper with the money and the parachutes.

The first two parachutes were provided by McChord Air Force Base. After receiving them, Cooper demanded two more. Perhaps the first parachutes wouldn’t have worked for his mission — they were military-grade, and the chutes would open after a 200-foot fall.

But the second set of parachutes were sports parachutes, brought from a nearby skydiving field. These would allow someone to free-fall for several thousand feet before the parachute opened.

At this point, the hijacker released the 36 passengers. He also let two crew members go, including Florence Schaffner. Then, D.B. Cooper told the pilot he wanted to fly to Mexico City. But the plane did not have the range to fly 2,200 miles to this destination, so Cooper agreed with the pilot to make a refueling stop in Reno along the way.

Federal Bureau of InvestigationD.B. Cooper left this tie aboard the plane when he jumped. The FBI later extracted a DNA sample from it.

Before they took off, he laid out specific demands for the flight. They must fly below 10,000 feet, with the wing flaps at 15 degrees, and keep the speed slower than 200 knots. And the rear door was to remain open.

As the plane rose into the sky around 7:40 p.m., several Air Force jets followed at a stealthy distance. Cooper sent the crew to the cockpit as it became deeply cold inside the plane. The four crew members on board later claimed that the temperature dropped to below zero.

Then, at 8:00 p.m., a warning light flashed in the cockpit, notifying them that the rear airstairs had been lowered. About 15 minutes later, the crew members noticed a sudden upward motion from the back of the plane. They remained huddled together, freezing, for nearly two hours.

Upon landing in Reno around 10:15 p.m., the plane was immediately surrounded by the local police and the FBI. They entered the plane and searched it from nose to tail. But there was no sign of D.B. Cooper — or the stolen money. Authorities were convinced that the hijacker could not have exited the plane on the ground without anyone seeing him.

D.B. Cooper had left behind two of the parachutes, his black clip-on tie, and a head-scratching mystery.

Who Was D.B. Cooper?

Wikimedia CommonsRemains of D.B. Cooper’s ransom money, which were discovered in 1980.

D.B. Cooper had vanished into thin air — literally. The authorities were astonished, especially since none of the fighter jets following the plane had seen him leave the aircraft. But the FBI felt confident they could track Cooper down — after all, they had a name, a physical description, and several specific details about the man.

But in reality, they had much less information than they thought they had. For starters, they quickly learned that Dan Cooper was not his real name. Adding to the confusion, the media reported that the hijacker’s name was “D.B. Cooper” — and it stuck.

Undeterred, the FBI took on the mystery with enthusiasm. The “NORJAK” investigation — short for Northwest Hijacking — was soon afoot and tips came pouring in. Ralph Himmelsbach, the FBI’s lead agent for the case, recalled that they had a long list of possible suspects. “Real, real good ones; real, real poor ones. A lot of both. And many in between,” he said.

Five years later, the FBI seemed to have hit a dead end. By that point, they had looked into more than 800 suspects. Of these, only two dozen were worth considering as the true perpetrator. By 2011, the FBI’s file on the case measured more than 40 feet long. And there was still no clear answer.

All the while, D.B. Cooper’s feat spread like wildfire in popular culture. It inspired songs, movies, books, and even the character of Dale Cooper on the television show Twin Peaks (the character’s full name is Dale Bartholomew Cooper, or D.B. Cooper).

A few prominent suspects emerged over the years, but none were charged. Five months after D.B. Cooper disappeared into the darkness, a man named Richard McCoy leapt from a plane over Utah with $500,000 in ransom money. McCoy was caught and sentenced to 45 years in prison. While he was originally deemed a NORJAK suspect, he was ruled out because he didn’t match the physical descriptions provided by the witnesses.

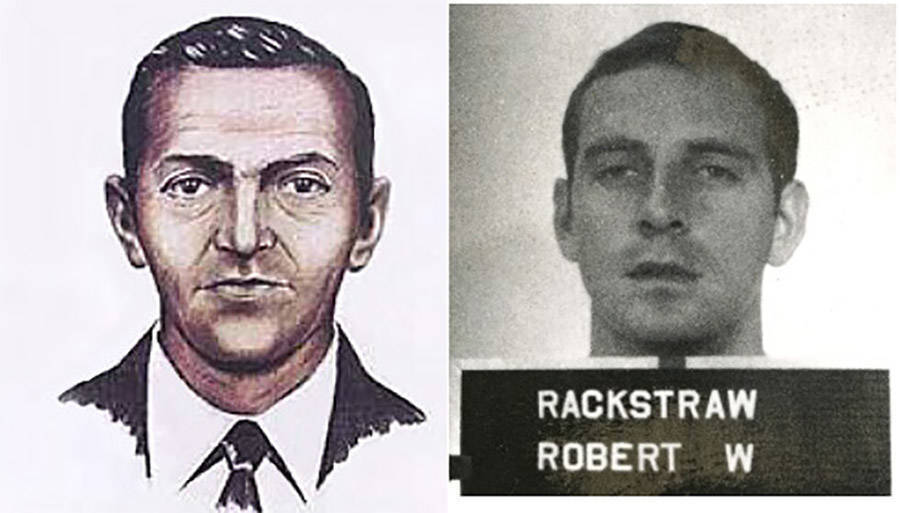

Wikimedia CommonsA sketch of D.B. Cooper next to a photograph of Robert Rackstraw.

Another prominent suspect was Robert Rackstraw. A former Special Forces paratrooper, Rackstraw certainly had the skill set to survive a leap from a plane in the dark. The FBI officially cleared him as a suspect in 1979, but some remain skeptical of his innocence to this day.

Filmmaker Thomas Colbert, who has independently investigated the case, believes that there is evidence linking Rackstraw to the crime — and it lies in a few letters that were allegedly written by Cooper shortly after the hijacking. Colbert also believes that the FBI is stonewalling and covering up Rackstraw’s tracks due to his possible ties to the CIA.

However, Geoffrey Gray, whose book Skyjack is considered one of the best on D.B. Cooper, disagrees. He claims that Rackstraw was not a serious suspect and does not even include him in his book.

In 1980, an 8-year-old boy on a camping trip near Portland made a thrilling discovery by the Columbia River: bundles of ragged dollar bills totaling $5,880. The serial numbers matched the ransom money given to D.B. Cooper nine years earlier. To this day, this remains the sole verifiable piece of evidence linked to the case that was found outside of the plane.

(Decades later, there were claims that pieces of one of the parachutes had been found, but it’s unclear whether those were ever officially verified.)

In 2001, the FBI lifted a DNA sample off Cooper’s tie, and used it to eliminate yet another suspect — Duane Weber — who had claimed to be D.B. Cooper on his deathbed. Years later, another man named Kenneth Christiansen was named in a magazine article as a potential Cooper. But he didn’t match the physical description, even though he was a skilled paratrooper.

A Seattle case agent named Larry Carr later said that D.B. Cooper was likely not a skilled skydiver. “We originally thought Cooper was an experienced jumper, perhaps even a paratrooper,” Carr said in 2007. “We concluded after a few years this was simply not true. No experienced parachutist would have jumped in the pitch-black night, in the rain, with a 200-mile-an-hour wind in his face, wearing loafers and a trench coat. It was simply too risky.”

Inside A Case That May Never Be Solved

Federal Bureau of InvestigationOne of the parachutes that D.B. Cooper left behind.

In 2016, the FBI announced that it would stop actively pursuing the case.

“Following one of the longest and most exhaustive investigations in our history,” the FBI said in a press release, “on July 8, 2016, the FBI redirected resources allocated to the D.B. Cooper case in order to focus on other investigative priorities.”

But even though the case is no longer active, the FBI encourages anyone with “specific physical evidence,” like more of the money or pieces of a parachute, to contact their local field office.

Meanwhile, amateur sleuths and independent investigators are still poring over the case. Often called “Cooperites,” they study all the information that they can get their hands on — and even host “CooperCons” to discuss the mystery and explore potential theories.

Of course, it’s very possible that D.B. Cooper simply did not survive his jump — and took all his secrets with him to his grave. The world may never know for sure, especially since the case is no longer active.

Even if the case is solved someday, perhaps the end result will be far more anti-climactic than one would expect. Maybe, Carr notes, it’ll simply take someone who “just remembers that odd uncle.”