The myth of the underworld, much like the myth of the lost paradise and the worldwide deluge, is a universal one. Cultures from all across the world, past and present, widely separated and with seemingly no historical contact, believed in this mysterious realm that the spirits of the deceased went to after death. Hell, the Christian version of the myth and Sheol, the Jewish variant, are very familiar in Western society, but the Greeks, Egyptians, and Maya all believed in their own version of this myth. In Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, Ignatius Donnelly argued that the universal myth of the lost paradise was referring to a real and physical place, but he did not mention the underworld. In this article, I shall extend Donnelly’s thesis and undertake an in-depth analysis of the underworld and where it may have been, and how a real and physical place might have become transformed into the final resting place of souls departed both in the physical and the mythological planes.

Realm of the Spirits

The Greeks believed that the underworld was very much a real place that the lucky few, blessed by the gods, could venture to. For example, Ulysses, in his quest to return to his wife and family on the island of Ithaca after the Trojan War, visited the underworld, meeting with the spirits of his father and the dead Achilles.

Moreover, they believed that the underworld was located in the far west, beyond the pillars of Heracles, somewhere where the sun continued to shine after it had already set over Greece itself. Hesiod placed the underworld in Oceanus, the western sea, or the Atlantic Ocean, and called it Hades.

Hell on Earth? The Location of the Underworld

Hades has been interpreted by contemporary scholars, and the Ancient Greeks themselves, as being an underground world. Could they both have been mistaken? Could the underworld, in actuality, have been not a world literally beneath our feet but a land so conspicuously low compared to other lands that it merited the designation of an underworld?

Although there are a million words in the English language, there are no words that describe the idea of a land below sea level. Even altitude and elevation, the words used to describe the height of a location above a given level, assume that the location being discussed is above sea level.

Mark Twain, best known for his novels, was also among the most quotable writers of his time. Among his memorable quotes is one that may be particularly relevant to unveiling the true nature of the underworld: “The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter, for it is the difference between the lightning bug and lightning.”

Could it be that the word “underworld” is just that, the exactly the right word for a land situated below sea level?

Map of the Caribbean Sea and Basin (Public Domain)

There are several advantages to this interpretation of the underworld. Firstly, there is strong evidence suggesting that a dry and habitable, below-sea-level basin did exist contemporaneously with behaviorally modern man, namely the Caribbean. Secondly, the Caribbean is exactly where the Ancient Greeks placed the underworld – somewhere in the remote west, across the Atlantic Ocean, for Ulysses was said to have “reached the far confines of Oceanus,” or the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, in his odyssey to the underworld. Thirdly, I shall demonstrate that an underworld that is a below-sea-level basin instead of an underground realm naturally and elegantly accounts for the transformation of Hades from a land of the living to the land of the dead. Finally, the Caribbean Basin contains within it a trench that strongly resembles a certain primordial abyss that features prominently in many Greek myths.

The possible location of the underworld of Tartarus and Hades. (Map Credit: Google Earth, 2017)

A Land of Life and a Land of Death

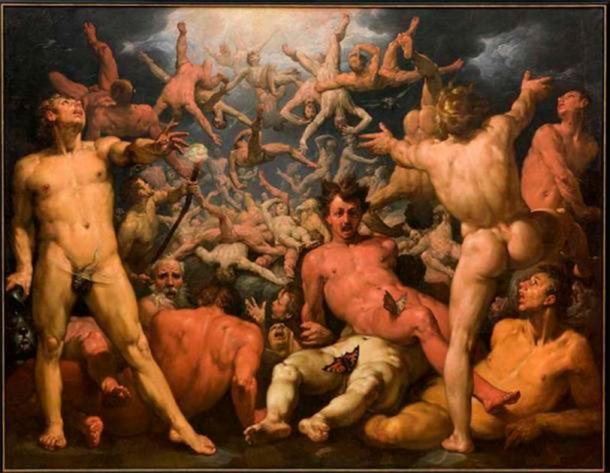

In the Odyssey, a myth dating back to the Heroic Age of Greece, Homer portrays the underworld as a gloomy realm of deceased spirits and shades. However, in myths that depict events taking place in the distant past, Hades is described as an abode of the living. For example, in the myth of the Titanomachy, or the war between the Titans and the Olympians, Zeus, son of Kronus, rebelled against his father and the Titans, the elder race of Gods, and emerged victorious in a ten-year-long war. Upon his victory, Zeus imprisoned the defeated Titans in Tartarus. There is no mention of spirits, shades, and ghosts in this version of Hades, and if Hesiod had called Hades and Tartarus by another name, one would hardly suspect that the setting of this war between the Titans and the Olympians was in any way a spiritual realm.

Fall of the Titans, 1588. (Public Domain)

In another myth, Persephone, the daughter of Zeus and Demeter, was out gathering flowers when Hades, the lord of the Underworld, ascended to the earth to carry her off to his realm, where he made her his queen. Demeter, in her grief at losing her daughter, sent a famine across the earth. At this point, Zeus intervened and sent Hermes, the messenger god to the underworld to secure the release of Persephone. Later on, he declared that Persephone would spend part of the year with Hades in the underworld and the rest of the year with her mother Demeter on Mount Olympus. Clearly in this myth Hades is portrayed as a real and physical land, suitable for habitation, instead of as a land of the dead. However, in the Odyssey, as was said earlier, Hades is portrayed as a land not of the living, but a land of the dead.

The Return of Persephone. (Public Domain)

Could it be that this transformation of Hades from a realm of the living to the realm of the dead in mythology and literature corresponds to a very real change in the physical realm?

John Martin’s The End of the World, which depicts the “destruction of Babylon and the material world by natural cataclysm”. (Public Domain)

If Hades, or the Greek underworld and the Caribbean Basin were one and the same, this dramatic shift in the way Hades is depicted finds a natural explanation – it was a land of the living before the cataclysm that formed the Caribbean Sea and became the land of the dead afterward. Interpreted in this way, Hades was originally a real and physical place that suffered a terrible cataclysm in which innumerable souls actually met their demise. Over time, with the passage of generations, the true nature of Hades as the resting place of the souls that perished in this cataclysm was forgotten, and became corrupted into the final resting place of all souls.

The Great Abyss on Earth

But even if it is granted that Hades was indeed a below sea level basin, how can one definitively establish that Hesiod was referring specifically to the Caribbean Basin, as opposed to other below sea level basins that may have existed in the remote past?

Hesiod also provides an interesting description of this mysterious realm of Hades. Namely, he situated Tartarus, the primordial abyss or chasm in which Zeus imprisoned the defeated Titans, within Hades, and said that an anvil dropped from the earth would take nine days to fall to Hades, and another nine to finally reach Tartarus. Also, in the Iliad, Zeus asserts that Tartarus is as far beneath Hades as heaven is above the earth.

If we equate Hades, the Greek Underworld, with the Caribbean Basin, one could interpret Hesiod’s cryptic description of the falling anvil to simply mean that Tartarus was an especially low place within the Caribbean Basin, an already deep, below-sea-level basin. The question that naturally follows is whether this basin contains within it a place that is especially low. Indeed, it most certainly does, for it contains within it a trench that is thousands of feet deeper than the average depth of the basin – the Cayman Trench. The Cayman Trench reaches a maximum depth of over 25,000 feet (7620 m) whereas the average depth of the Caribbean Basin is just over 7,000 feet (2134 m). Not only is Tartarus analogous to the Cayman Trench in its exceeding depth, it is also described as, quite literally, a chasm and an abyss by none other than the great philosopher Plato, which is essentially identical to a trench. Plato, in his Phaedo, writes:

“One of the chasms of the earth happens to be greater than the rest and is bored right through the whole earth, this of which Homer himself says,

‘Far off, where deepest beneath the earth is an abyss;’ and which elsewhere he and many other poets have called Tartarus.

For all the rivers flow together into this chasm and flow out of it again; and each becomes such, as the earth through which it also flows.”

Water pours down over a rocky ledge and into valley basin below. (CC BY-ND 2.0)

Could it be that Hades was not only transformed from an abode of the living to the abode of the dead by a terrible cataclysm, but that Hades was also, prior to the cataclysm, a veritable paradise? That is, might Heaven have become Hell? The Ancient Greeks and Phoenicians believed that the Gardens of the Hesperides, like Hades, was also located in the remote West. Strangely enough, the garden also closely resembles the geography of the Caribbean Basin. Quoting Ignatius Donnelly’s Atlantis: The Antediluvian World:

“According to the traditions of the Phoenicians, the Gardens of the Hesperides were in the remote west…The Greek mythology, in speaking of the Garden of the Hesperides, tells us that ‘the outer edge of the garden was slightly raised, so that the water might not run in and overflow the land.’”

The Garden of Hesperides, guarded by the serpent. (Public Domain)

As was demonstrated in a previous article, a dry Caribbean Basin could have existed only if there had been continuous chain of land rising uniformly above sea level forming a barrier, a giant earthen dam so to speak, to keep the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans at bay. Notably, the resemblance is not merely one of structure in that both the Gardens of the Hesperides and a dry Caribbean Basin had an elevated boundary, but also of function, for both the “outer edge of the garden” and the “continuous chain of land” act as a barrier preventing the water from flowing into the respective lands.

Could such a profound similarity between the Caribbean Basin and the Gardens of Hesperides, be dismissed as mere coincidence? When Christopher Columbus set foot on the South American mainland on his third voyage near the mouth of the Orinoco River, he believed that he had found the Garden of Eden, the lost paradise. Perhaps the Admiral of the Ocean Sea was not far off the mark after all, and more besides, perchance he found not only The Garden of Eden, but also Hades itself…