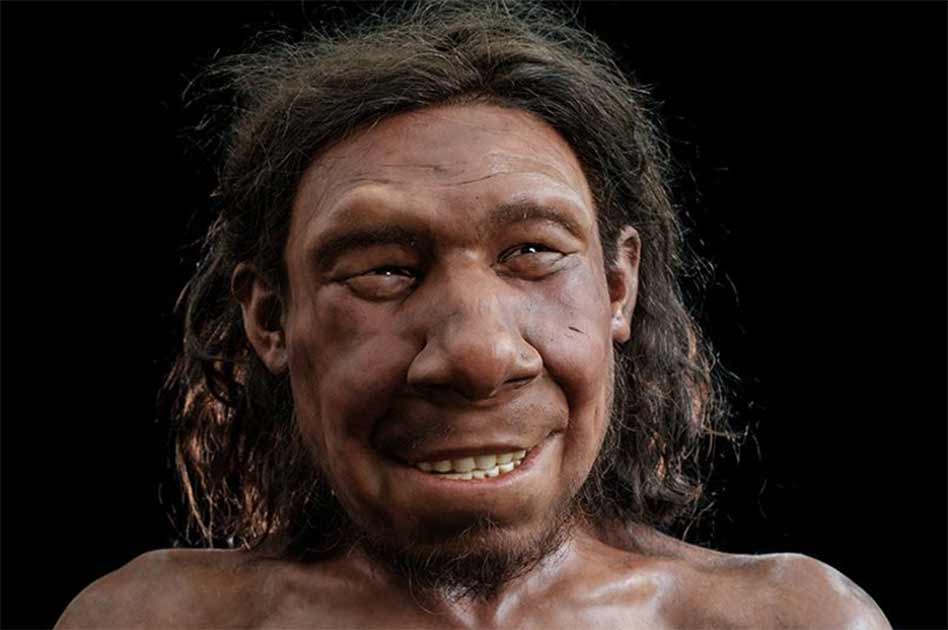

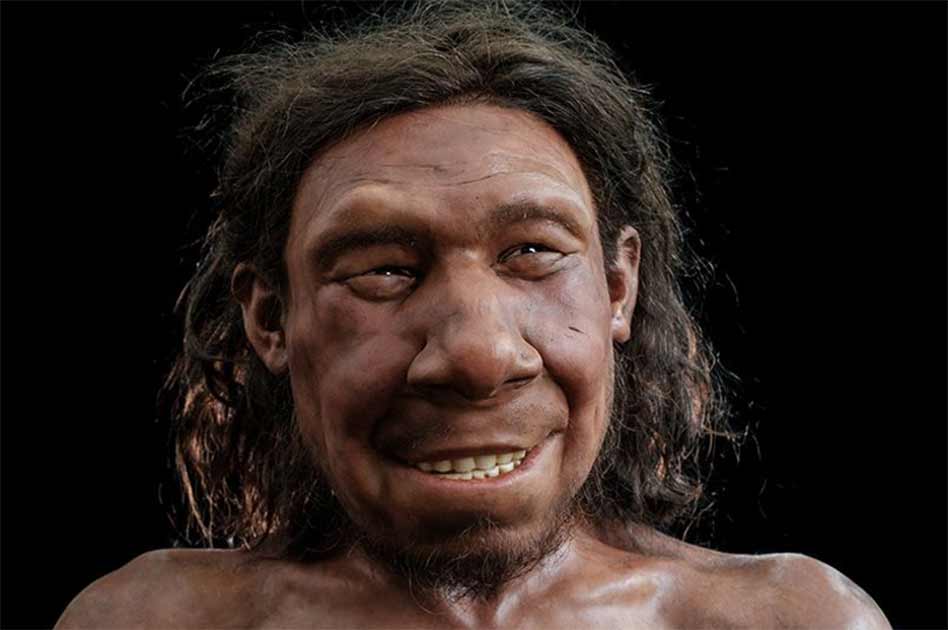

The first-ever Neanderthal found in The Netherlands, who scientists call Krijn, has now been brought more fully to life. A pair of “paleo-artists” who specialize in making life-like reconstructions of fossilized specimens have provided the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities (Rijksmuseum van Oudheden) with a sculpted version of this young Neanderthal’s face. The Kennis Brothers, who are based in Arnhem in the Netherlands, have chosen to portray Krijn with a big smile, which counteracts the usual dour image of our long-extinct evolutionary cousins.

The First Neanderthal in The Netherlands

When a piece of skull bone from a Neanderthal was found on a beach in the Dutch province of Zeeland more than a decade ago, no one dreamed it would be possible to figure out what that Neanderthal looked like based on such a small fragment. But scientists have learned a lot about Neanderthal characteristics from studying various fossilized skeletons recovered from around the world. This has allowed them to make precise estimates about Neanderthal appearance, both in general and for specific skeletal finds.

The Neanderthal Krijn’s fossil eyebrow arch (© Servaas Neijens/Rijksmuseum)

Scientists from Leiden University and the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig studied the skull fragment found on the beach in Zeeland for several years. From the information they gathered, they were able to generate digital images of what Krijn probably looked like. These images proved highly useful to Alfons and Adrie Kennis, who were able to sculpt a detailed three-dimensional approximation of Krijn’s appearance that experts believe is highly accurate.

One of the phases in the construction of the face (© Kennis & Kennis Reconstructions / Rijksmuseum)

Who Was Krijn the Neanderthal?

Krijn’s skull fragment was originally buried on the bottom of the North Sea. It was dug up and washed ashore during a dredging operation off the western Dutch coast, where it was discovered by amateur paleontologist, Luc Anthonis, in 2009. Anthonis passed the skull fragment on to the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, where it was identified as the bone of an eyebrow ridge that belonged to a Neanderthal who lived sometime between 50,000 and 70,000 years ago.

This was a remarkable discovery, because it was the first evidence ever found that showed a Neanderthal presence in The Netherlands.

A deeper examination by the Leiden University and the Max Planck Institute scientists revealed even more details about the skull fragment and its prehistorical owner. They determined the fragment had come from a young man of stocky build. A study of the isotopes locked up in the bone showed the young man’s diet consisted primarily of meat, which would be expected for someone who lived in a Neanderthal hunter-gatherer society in the ancient past.

Inside the eyebrow ridge bone, the scientists found an unusual hollowed-out area they concluded had been occupied by some type of tumor. This tumor was entirely benign, and except for its effect on Krijn’s appearance (it would have caused a swollen bump over his eye) it had no impact on his health.

Such a tumor has never been seen before in any other Neanderthal specimen, and its presence helped the Kennis Brothers create a facial reconstruction that is entirely unique among Neanderthal sculptures.

Note the lump over Krijn’s right eye, representing the tumor that was evident from the skull fragment. (© Servaas Neijens / Rijksmuseum)

Neanderthal Adventures in Doggerland

While the skeletal remains were technically found on Dutch soil, it should be noted that they originally came from off the Dutch coast. Krijn’s remains were buried at the bottom of the North Sea, which revealed something quite significant about his past.

Over the course of the Last Glacial Period, or Ice Age, sea levels rose and fell with the alternating advance and retreat of the earth’s glacial cover. When Krijn lived, sea levels in the northern hemisphere were relatively low, and in the North Sea they were 165 feet (50 meters) lower than they are today. The North Sea was much smaller at that time, and in what is now its southern and western parts the lowering of sea levels exposed a land bridge that connected the islands of the United Kingdom with continental Europe.

This land bridge is known as Doggerland, and it was located directly to the west of what is now the Dutch seacoast province of Zeeland. So while Krijn and his people might have traveled through Dutch territory, when he died, he died in Doggerland, where presumably he resided with his people most of the time.

During the last Ice Age, Doggerland stayed above sea level for tens of thousands of years. It even remained above water for a while after the Ice Age ended, in 9,700 BC. The last of its land area was submerged under the surface of the North Sea in approximately 5,800 BC, or a few thousand years after the Bering Strait land bridge that connected Asia with the Americas disappeared beneath the rising waters of the Pacific.

Over the course of its long history, a thriving and diverse ecosystem developed on Doggerland. Neanderthals existed alongside mammoths, woolly rhinoceroses, reindeer, wild horses, and many other large land animals that roamed far and wide in the northern hemisphere in prehistoric times. Modern humans eventually arrived on Doggerland as well, and remained there living as hunter-gatherers right to the end.

Neanderthals would have lived on Doggerland with modern humans for a time. But Neanderthals went extinct long before Doggerland did, so Krijn’s people were not around to see the final demise of their homeland.

Dutch archaeologists and paleontologists know that Doggerland has many secrets to reveal. Unfortunately, underwater exploration is expensive and difficult in the North Sea, given the murkiness of its waters and the depth at which Doggerland’s most fascinating treasures are buried. For now, the underwater remains of Doggerland remain largely inaccessible, forcing scientists to rely on dredging and fishing operations to pull up the occasional exciting specimen or artifact.