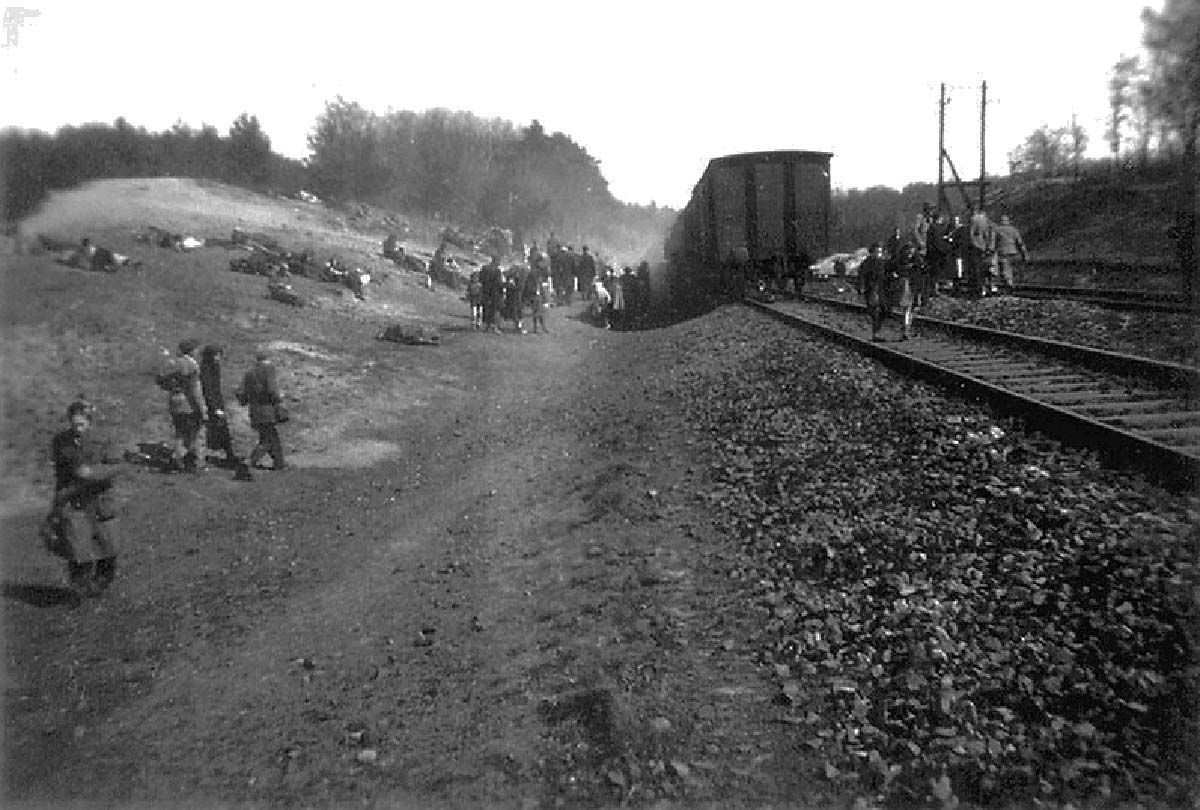

Picture was taken by Major Clarence L. Benjamin at the instant a few of the train people saw the tanks and first realized they had been liberated.

It’s Friday, the 13th of April, 1945. A few miles northwest of Magdeburg there was a railroad siding in a wooded ravine not far from the Elbe River.

Major Clarence L. Benjamin in a jeep was leading a small task force of two light tanks on a routine job of patrolling. The unit came upon some 200 shabby-looking civilians by the side of the road.

There was something immediately apparent about each one of these people, men, and women, which arrested the attention. Each one of them was skeleton thin with starvation, a sickness in their faces, and the way in which they stood-and there was something else.

At the sight of Americans they began laughing in joy-if it could be called laughing. It was an outpouring of pure, near-hysterical relief. The tankers soon found out why. The reason was found at the railroad siding.

There they came upon a long string of grimy, ancient boxcars standing silent on the tracks. In the banks by the tracks, as if to get some pitiful comfort from the thin April sun, a multitude of people of all shades of misery spread themselves in a sorry, despairing tableau.

As the American uniforms were sighted, a great stir went through this strange camp. Many rushed toward the Major’s jeep and the two light tanks.

On the hill to the left are people resting – some forever. Some sixteen died of starvation before food could be brought to the train.

Bit by bit, as the Major found some who spoke English, the story came out. This had been and was a horror train. This train which contained about 2,500 Jews, had a few days previously left the Bergen-Belsen death camp.

Men, women, and children were all loaded into a few available railway cars, some passenger and some freight, but mostly the typical antiquated freight cars, termed as “40 and 8” a WWI terminology.

This signified that these cars would accommodate 40 men or 8 horses. They were crammed into all available space and the freight cars were packed with about 60 – 70 people, with standing room only for most of them, so that they were packed in like sardines.

This train which contained about 2,500 Jews, had a few days previously left the Bergen-Belsen death camp.

As the war came to an end, Nazis made attempts to evacuate concentration camps before Allied troops arrived. Three trains were sent from Bergen-Belsen on April 10, 1945, with the purpose to move eastward from the Camp to the Elbe River, where they were informed that it would not be advisable to proceed further because of the rapidly advancing Russian Army.

The train then reversed direction and proceeded to Farsleben, where they were then told that they were heading into the advancing American Army.

Consequently, the train halted at Farsleben and was awaiting further orders as to where to go next. The engineers had then received their orders, to drive the train to, and onto the bridge over the Elbe River, and either blow it up, or just drive it off the end of the damaged bridge, with all of the cars of the train crashing into the river, and killing or drowning all of the occupants.

The engineers were having some second thoughts about this action, as they too would be hurtling themselves to death also this is the point at which they were discovered, just shortly after the leading elements of the 743rd Tank Battalion arrived on the scene.

The little fellow was pleased with having his picture taken.

They were crammed into all available space and the freight cars were packed with about 60 – 70 people.

The attempt was evidently to get them to a camp where they could be eliminated before they could be liberated.

This is Gina Rappaport, who spoke very good English and spent a couple of hours telling her story to the American troops. She was in the Warsaw ghetto under terrible conditions and then was sent to Bergen-Belsen.

Most of these Jews were from Poland, Russia, and other Eastern countries, so with the total destruction of their homes, loss of families, and the serious prospects of coming under the jurisdiction of the Soviets, most were fearful about their future.

Most chose the option of remaining in Germany or the possibility of being repatriated to some other Western European countries. Eventually, many were finally repatriated to Israel, South American countries, for which many had passports, England, Canada, and to the United States of America.

Near the end of the war, when Germany’s military force was collapsing, the Allied armies closed in on the Nazi concentration camps. The Germans began frantically to move the prisoners out of the camps near the front and take them to be used as forced laborers in camps inside Germany. Prisoners were first taken by train and then by foot on “death marches”, as they became known.

Prisoners were forced to march long distances in the bitter cold, with little or no food, water, or rest. Those who could not keep up were shot. The largest death marches took place in the winter of 1944-1945 when the Soviet army began its liberation of Poland.

Nine days before the Soviets arrived at Auschwitz, the Germans marched tens of thousands of prisoners out of the camp toward Wodzislaw, a town thirty-five miles away, where they were put on freight trains to other camps. About one in four died on the way.

The Nazis often killed large groups of prisoners before, during, or after marches. During one march, 7,000 Jewish prisoners, 6,000 of them women, were moved from camps in the Danzig region bordered on the north by the Baltic Sea.

On the ten-day march, 700 were murdered. Those still alive when the marchers reached the shores of the sea were driven into the water and shot.