Between February and May 1971, Juan Corona killed 25 migrant workers with a machete and buried their bodies in crude, shallow graves near Yuba City, California.

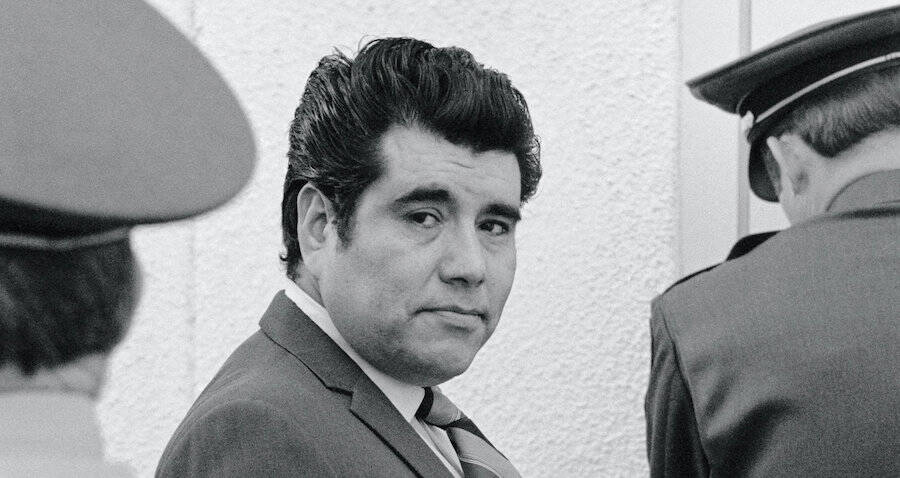

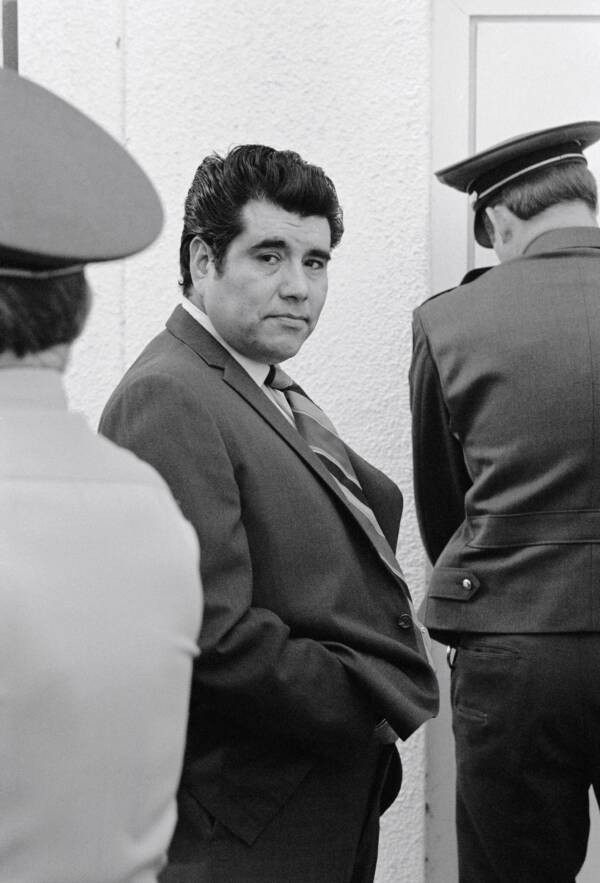

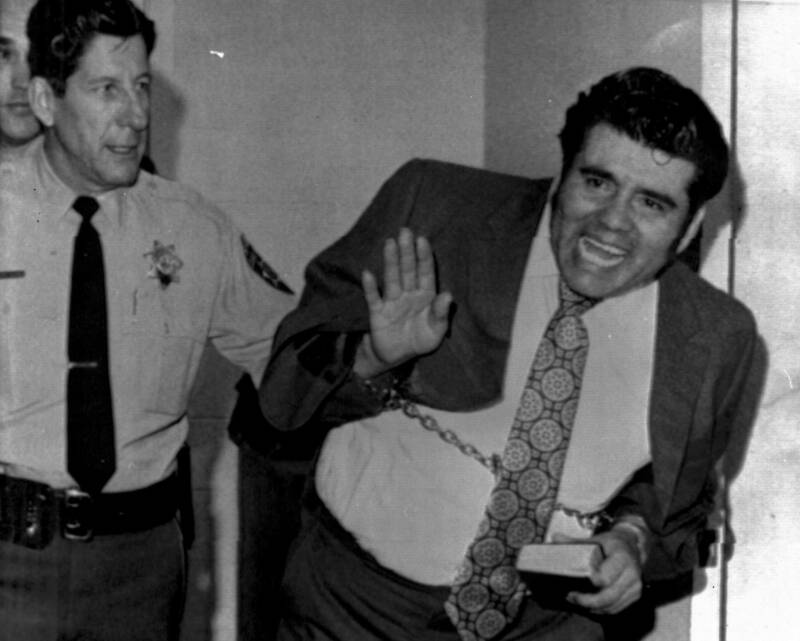

TwitterJuan Corona became known as the Machete Murderer after he brutally killed 25 migrant workers in 1971.

On May 19, 1971, a peach farmer living near Yuba City, California noticed a suspicious, freshly dug hole in one of his orchards. Later that day, he noticed that someone had filled it in — and when police arrived, they discovered a man’s dead body buried in the hole, his head split open. What’s more, they found several other freshly dug graves scattered across the orchards. In total, they uncovered 25 corpses.

It wasn’t difficult for investigators to link the victims to a single man: Juan Corona. His name was on store receipts and back-deposit slips found in several of the graves. At his home, police found a bloody machete and a ledger with some of the victims’ names. They had all been migrant workers hired by Corona.

Corona maintained his innocence for years, despite being convicted twice, until a parole hearing in December 2011 where he admitted, for the first time publicly, that he had indeed murdered 25 migrant workers in the early 1970s.

Corona, a hardworking man with a wife and four daughters, seemed at first an unlikely murderer. But as more information about the prolific killer came to light, his history of mental illness and quick temper revealed his true, dark nature.

Who Was Juan Corona?

Juan Vallejo Corona was born on Feb. 7, 1934 in Autlán, Jalisco, Mexico. At 16, he crossed the border into the United States, working as a laborer in the Imperial Valley in California for three months picking carrots and melons. Then, he made his way north into the Sacramento Valley.

Back in 1944, his half-brother Natividad Corona had immigrated to Marysville, California, and at his suggestion, Juan eventually moved to Yuba City, just across the river from Marysville, in 1953. There, he worked on a ranch and met his first wife Gabriella Hermosillo.

But life soon took a turn for the worse for Juan Corona.

Juan Corona’s Mental Health Struggles

In 1955, a flood swept through Sutter County and killed dozens of people. Juan Corona became convinced that he was perpetually surrounded by the ghosts of those who had died in the flood.

What’s more, Corona’s family would later report that he had a violent temper — so much so that they sometimes had to tie him up with ropes to subdue him,

In 1956, Corona’s brother committed him to a mental hospital, where he was diagnosed with “schizophrenic reaction, paranoid type,” according to The Union, and received 23 electroshock treatments for his mental illness. Three months later, doctors proclaimed that he had recovered and released him.

According to the San Francisco Chronicle, Corona was deported to Mexico upon his release, but he quickly returned to California with a green card, ready to make a fresh start.

Corona was considered to be a hard worker, and eventually worked his way up from being a farm laborer to a labor contractor. His first marriage had ended, but by 1960 he had married his second wife, Gloria, with whom he would have four daughters. Aside from his quick temper and occasional schizophrenic episodes, Corona’s life seemed relatively stable.

It didn’t last long, though. In March 1970, Juan Corona was once again hospitalized for schizophrenia, and his business was suffering due to increasing agricultural mechanization. In 1971, he applied for welfare. His application was denied, and he flew into a fit of rage.

That same year, police would find 25 mutilated bodies buried in holes across the valley, all evidence leading back to Juan Corona.

Juan Corona’s Murder Spree Comes To Light

Juan Corona was contracted by local farmers to find workers, but instead, he found himself victims.

Between February and May of 1971, Corona hired, and then murdered, a series of migrant workers with no ties to the area. Most of them were “fruit tramps” living on skid row in Marysville, men who followed orchard harvests to find work.

TwitterInvestigators were never able to determine a motive for Juan Corona’s murders.

Corona’s crimes were finally revealed on May 19, 1971 when a farmer noticed a freshly dug hole in one of his peach orchards. Suspecting someone was dumping trash there, the farmer called the police, who quickly discovered that the hole was being used as a shallow, crude grave.

According to the Los Angeles Times, the body exhumed was later identified as Kenneth Whitacre, a 40-year-old unhoused man.

Soon enough, police discovered even more shallow graves littering the orchards, including at the nearby Sullivan Ranch where Juan Corona housed some of the laborers he hired. Over the course of several weeks, investigators uncovered 25 bodies, most crudely hacked into with a machete. All but one had suffered severe injuries to the head. Some of them had stab wounds in addition to slices across their bodies.

Several victims had receipts or other documents with Juan Corona’s name on them, and when police searched Corona’s home, they found a bloodstained machete, a post-hole digger, a gun, and a ledger with eight of the victims’ names. They arrested him one week after the first body was discovered.

The press dubbed him, the “Machete Murderer.”

Despite a wealth of evidence, however, Corona’s trial was embarrassingly messy.

The Trial — And Retrial — That Put The ‘Machete Murderer’ Behind Bars

Juan Corona’s first trial began in September 1972 with a stunning lack of decorum. One of Corona’s sisters blocked an entrance to the courthouse by lying in front of it, for which she was later arrested, and both the defense and the prosecution made a series of embarrassing blunders.

The prosecution, for example, misplaced and mishandled evidence. Forensic tests were delayed. The defense, meanwhile, shocked jury members by refusing to submit psychiatric evidence on Corona’s behalf. Corona’s lawyer was hoping to score a book deal about the case, and opted not to have Corona plead not guilty by reason of insanity.

The trial ended with Corona’s conviction in January 1973. He was sentenced to 25 consecutive life sentences — California’s death penalty had been abolished just a few months earlier. Shortly after his imprisonment, Corona was stabbed 32 times and lost an eye in an attack from another inmate, and his wife divorced him.

Five years later, however, an appellate court overturned the conviction, saying that Corona’s defense attorney had launched a farcical defense and failed to call in rebuttal witnesses to counter the prosecution’s 119 witnesses.

Sutter County Police Department Juan Corona shortly before his death at 85.

A second trial for Corona began in 1982, during which his defense once again surprised the jury by offering an alternative story behind the grisly murders. This time, they attempted to put the blame on Corona’s late half-brother, Natividad, who the defense referred to as an “aggressive homosexual.”

Natividad was fueled by a “maniacal rage,” they claimed, resulting from “the frustration of a morbid sexuality.” This time, Juan Corona also took the stand and denied any involvement in the slayings.

The jury didn’t buy this new argument, and once again found Corona guilty on all charges.

In Juan 2011, Corona finally admitted, publicly, to the killings. He described his victims as “winos” and “creeps” who had been trespassing on the orchards. When asked if he felt remorse for his actions, he was dodgy, giving a sort of non-answer ending with, “So I went and buy the machete and then okay, I started killing when I had to kill all those persons, one by one.”

Juan Corona died in prison on March 4, 2019 of natural causes. He was 85 years old.