Since 1933, the Lycoming Division of the Aviation Manufacturing Corporation had worked to create a high-power engine for the United States Armed Forces. Its first attempt was the 1,200 hp (895 kW), 12-cylinder O-1230, which was outclassed by the time it first flew in 1940. Lycoming’s second attempt was the 2,300 hp (1,715 kW), 24-cylinder XH-2470. The engine had shown some promise, but its performance was eclipsed by other engines when the XH-2470 was first flown in 1943. Lycoming set out to design an engine that was more powerful than any other and that would meet the power needs of future large aircraft.

The Lycoming XR-7755 was the most powerful aircraft engine in the world when it was built. The XR-7755 was the culmination of Lycoming’s experience with radial and liquid-cooled engines. Conceived in 1943, such a large engine was not needed by the time it first ran in 1946.

In mid-1943, Lycoming engaged in talks with personnel from the US Army Air Force (AAF) at Wright Field, Ohio. Different sources list the involvement of the Air Materiel Command, Air Technical Service Command, and the Power Plant Lab. By December 1943, the engine concept had been solidified as a very large displacement, high-compression, liquid-cooled engine designed for optimum fuel economy and intended to power the next generation of very large aircraft. Lycoming’s experimental engine was designated XR-7755 and given the “Materiel, Experimental” code MX-434.

Clarence Wiegman headed the Lycoming XR-7755 design team. The engine consisted of nine banks of four inline cylinders positioned radially with 40-degrees of separation around a forged steel crankcase. This formed a 36-cylinder inline radial engine. The crankcase was made up of five sections, each split vertically through the cylinders. The crankcase sections were secured together by nine bolts that extended the length of the case. The individual steel cylinders each had their own water jacket. Each bank of four cylinders shared a common cast aluminum cylinder head. Each four-cylinder bank was secured to the crankcase by 16 long studs that passed through the cylinder head.

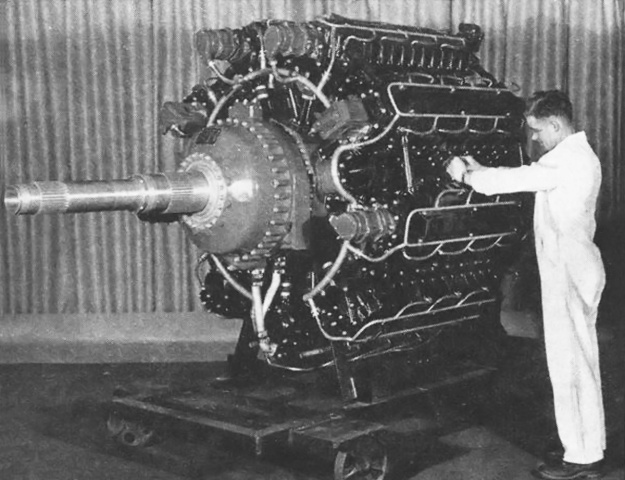

The worker gives some perspective to the XR-7755’s large size. However, the engine’s three-ton (2.74 t) weight is hard to imagine. The engine’s two magnetos and four distributors are visible on the front of the cylinder banks.

Each cylinder had one intake and one exhaust valve. Both valves were sodium cooled, with a hollow stem for the intake valve and a hollow stem and head for the exhaust valve. The valves for each bank of cylinders were actuated by a single overhead camshaft, driven via a vertical shaft at the front of the engine. Each camshaft had two sets of lobes for different valve timing—one lobe set was optimized for power and the other set for economic cruise. The camshafts shifted axially to engage the desired set of lobes. When the camshaft was shifted, the spark plug timing was automatically changed. Ignition was provided by two magnetos and four distributors. Each unit was camshaft-driven and mounted to the front of a separate cylinder bank. The spark plug leads passed through the valve covers and to the spark plugs, which were positioned in opposite corners of each cylinder.

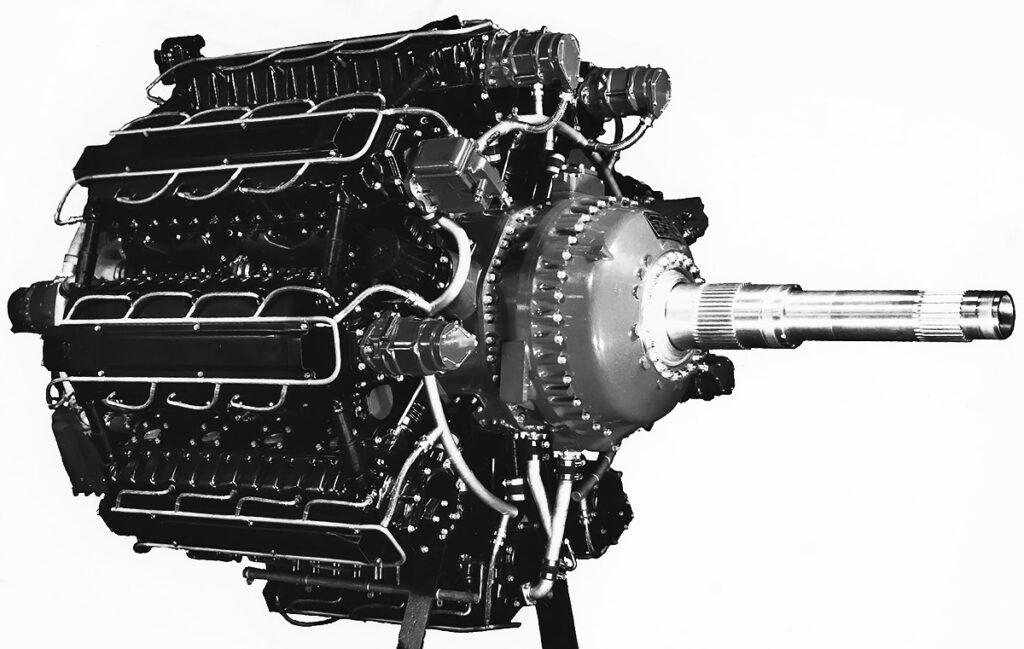

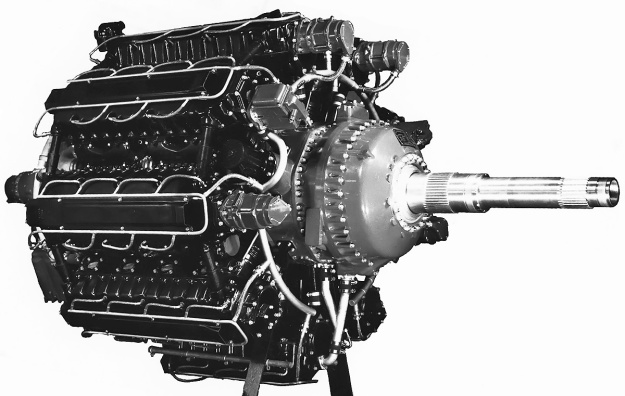

The XR-7755-1 on the test stand with its single propeller shaft. With each of the 36-cylinders displacing 215 cu in (3.5 L), witnessing the XR-7755 run was most likely a very memorable event. Note the robust upper engine support.

The crankshaft had four crankpins, each spaced at 180 degrees. The crankshaft was made up of five sections and assembled through the four one-piece master connecting rods. The crankshaft sections were joined at the rear of the crankpin via face splines and secured by four bolts. Five roller bearings supported the crankshaft in the crankcase.

At the rear of the engine was a single-stage, single-speed supercharger. The supercharger’s impeller was 14.4 in (366 mm) in diameter and spun at six times crankshaft speed. The supercharger fed air to nine intake manifolds, each mating with the right side of a cylinder bank. Fuel was provided to the cylinder via either a carburetor or fuel injection. Individual exhaust stacks were attached to the left side of each cylinder. Provisions were also made to incorporate two turbosuperchargers.

Although a single rotation engine was tested, the engine accommodated contra-rotating propellers using SAE #60L-80 spline shafts. The inner shaft rotated counterclockwise, and the outer shaft rotated clockwise. A two-speed planetary propeller gear reduction was hydraulically shifted by engine oil boosted to 300 psi (20.68 bar) by a pump in the nose case. A .2460 reduction was available for high engine speeds, and a .3536 reduction was used for cruise operations with low engine rpm. Due to its size, the XR-7755 required two starters. Both starters were mounted vertically on the crankcase in front of the cylinder banks; one was at the 2:30 position, and the other was at the 9:30 position.

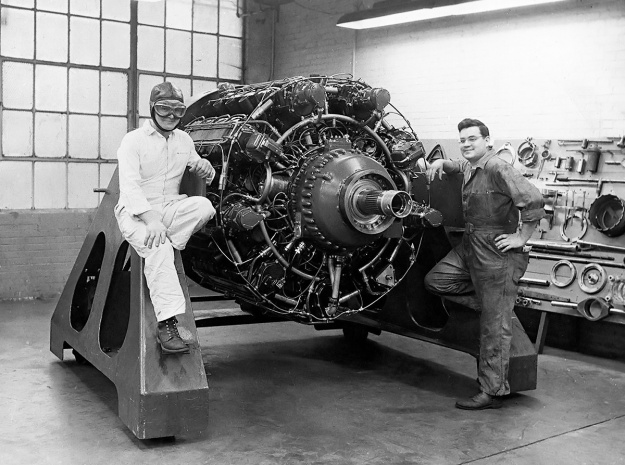

Lycoming workers Red Maxwell (left) and Paul Cervinsky (right) pose next to the completed XR-7755-1. It appears Maxwell is ready for the big engine to be stuffed in an airframe to see what it will do. Note the ring on the nose case and around the propeller shaft. No other image found has that ring.

The XR-7755 had a 6.375 in (162 mm) bore and a 6.75 in (171 mm) stroke. The engine displaced 7,756 cu in (127.1 L) and had a compression ratio of 8.5 to 1. The XR-7755 produced 5,000 hp (3,728 kW) at 2,600 rpm (.2460 propeller gear) for takeoff, 4,000 hp (2,983 kW) at 2,300 rpm (.2460 propeller gear) for normal operation, and 3,000 hp (2,237 kW) at 2,100 rpm (.3536 propeller gear) for cruise power. Specific fuel consumption at normal cruise power was .43 lb/hp/hr (262 g/kW/hr), but the rate dropped to around .38 lb/hp/hr (231 g/kW/hr) at low cruise power of around 1,500 hp (1,119 kW). The engine was 61.0 in (1.55 m) in diameter, 66.25 in (1.68 m) tall, and 121.35 in (3.08 m) long. The XR-7755 weighed 6,050 lb (2,744 kg).

Lycoming ad from December 1946 featuring the XR-7755. If the engine was not going to go into production, Lycoming might as well get some press out of it. One can only wonder how those responsible for marketing imagined the huge, liquid-cooled engine would factor into the decision-making process of a person buying a small, air-cooled engine.

The XR-7755 was first run in July 1946. At the time, some 10,000 hours of single-cylinder testing had been completed. The Lycoming factory was located near a residential area. Reportedly, a nearby grocery store’s canned goods would vibrate off the shelves as the XR-7755 underwent high-power tests. A good neighbor, Lycoming went to the store and installed strips on the shelf edges to keep the cans from falling. At takeoff power, the XR-7755’s fuel consumption was 580 gallons (2,196 L) per hour, or 20.62 fl oz (.61 L) per second. The engine’s coolant pump flowed 750 gpm (2,839 l/m) to dissipate 95,600 BTUs (24,107 kcal) per minute. That is 2,504 hp (1,681 kW) of heat being rejected into the coolant, and the system’s flow rate was enough to fill a 55 gallon (208 L) drum every 4.4 seconds. The oil pump circulated 71 gpm (269 l/m) at 100 psi (6.89 bar). The oil system absorbed 25,500 BTUs (6,430 kcal) per minute, which is 601 hp (448 kW). Lycoming had an optimistic opinion of the engine and believed that an output of 7,000 hp (5,220 kW) was possible.

Most sources indicate that two XR-7755 engines were built: an XR-7755-1 with a single rotation propeller shaft and an XR-7755-3 with a contra-rotating propeller shaft. Both of these engines used carburetors. There is some indication, including the recollections of those who had family members involved with the project, that a third engine was built: an XR-7755-5 with fuel injection. Reportedly, the -1 underwent a 50-hour test run, but the results are not known. The -3 was delivered to the AAF in 1946, but it is unlikely this engine underwent much testing. It is not clear what happened to the -5, if it was completed. By the time the XR-7755 had run, the concept of an aircraft larger than the Convair B-36 Peacemaker had fallen out of favor, as had the idea of modifying the B-36 with larger piston engines. Rather, jets would be used to improve performance of the aircraft. There was no application for the XR-7755 in a post-war world with the performance of jet aircraft quickly being realized. The XR-7755 never flew.

The XR-7755 on display at the Army Air Forces Fair held at Wright Field, Ohio in October 1945. Note what appears to be a mockup of the contra-rotating propeller shafts.

One curious anomaly in the XR-7755’s story is an appearance of the engine at the Army Air Forces Fair held at Wright Field, Ohio in October 1945. This predates the engine’s run date and its supposed delivery to the AAF. However, the engine appears to have a mockup of its contra-rotating propeller shafts installed. It would seem that the engine is not complete and was shipped the 460 miles (740 km) from Lycoming’s factory in Williamsport, Pennsylvania to Dayton, Ohio to be displayed with other unusual treasures from the war. Presumably, the engine was returned to Lycoming after the show and was subsequently completed and tested in 1946.

The sole XR-7755-3 has been preserved by the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum and is on display in the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia. Many consider the XR-7755 the largest aircraft engine ever built. However, the Soviet IAM M-44 (8,107 cu in / 132.8 L) of 1933 and Yakovlev M-501 (8,760 cu in / 143.6 L) of 1952 were larger engines. At the time it first ran, the XR-7755 was the world’s most powerful reciprocating aircraft engine.

The restored XR-7755-3 on display in the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. The bottom of the engine is on the left, marked by the drain tube from the gear reduction housing and the sump built into the valve cover. Note the two spark plug leads for each cylinder passing through opposite sides of the valve covers. (Sanjay Acharya image via Wikimedia Commons)

Sources: – “5,000-Hp. Lycoming Revealed” by J. H. Carpenter, Aviation (December 1946) – Lycoming XR-7755 Aircraft Engine and Engineering Laboratories by Lycoming Division, The Aviation Corporation (31 October 1946) – “The Evolution of Reciprocating Engines at Lycoming” by A. E. Light, AIAA: Evolution of Aircraft/Aerospace Structures and Materials Symposium (24–25 April 1985) – Aircraft Engines of the World 1948 by Paul Wilkinson (1948) – The History of North American Small Gas Turbine Aircraft Engines by Richard A. Leyes II and William A. Fleming (1999) – Studebaker’s XH-9350 and Their Other Aircraft Engines by William Pearce (2018) – https://generalaviationnews.com/2007/04/20/the-xr-7755-the-whole-story/ – https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/lycoming-xr-7755-3-radial-36-engine