The movie can be experienced as pure spectacle, I suppose, if we give up all hopes of making sense of it. Bombs explode and planes crash and the theater shakes with the magic of Sensurround. But there’s no real directorial intelligence at hand to weave the special effects into the story, to clarify the outlines of the battle and to convincingly account for the unexpected American victory.

There’s one curious thing, though: Throughout the movie, the Japanese seem pessimistic, bitter, taciturn, as if they know they’re going to lose. The characterization of the Japanese officers in “Midway” is, in fact, the most distracting thing about the movie. They speak in English (instead of in subtitles as in “Tora! Tora! Tora!”), but they’re never allowed to have the human quirks of their American counterparts. While Fonda and Holbrook and Robert Mitchum and Glenn Ford are working away at being droll and sly and wise, the Japanese speak in monosyllables punctuated by deep, meaningful pauses.

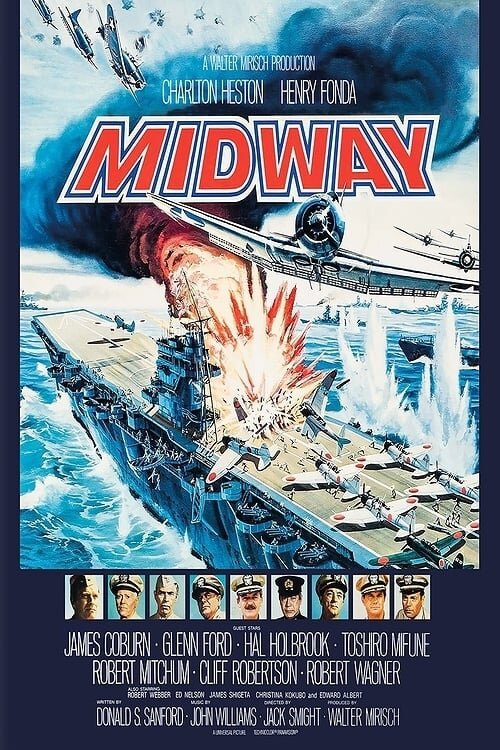

The hero of the movie is that veteran of countless previous epics, Charlton Heston. He brings a suitably heroic stature to his role, and, toward the movie’s end, we’re not surprised when he climbs into a plane and personally attacks the remaining Japanese carrier. He’s good at that — he looks right at home in the cockpit, as indeed he should after “Airport 1975” — but he barely makes it through some scenes with his son (Edward Albert).

These are supposed to provide what little human interest the movie allows us. The son is engaged to marry a Japanese-American girl, but she has been detained for security reasons. Albert pleads with his father to pull some strings, and the father does, but not before some terribly awkward moments. Heston is a professional actor, and rarely at a loss, but Albert seems so uncomfortable and stiff. War movies used to have dash and color and a certain corny sentimentality; “Midway” hardly even makes us care.