Before Harold Edgerton rigged a milk dropper next to a timer and a camera of his own invention, it was virtually impossible to take a good photo in the dark without bulky equipment.

Before Harold Edgerton rigged a milk dropper next to a timer and a camera of his own invention, it was virtually impossible to take a good photo in the dark without bulky equipment.

It was similarly futile to try to photograph a fleeting moment. But in the 1950s at his lab at MIT, Edgerton started tinkering with a process that would change the future of photography.

There the electrical-engineering professor combined high-tech strobe lights with camera shutter motors to capture moments imperceptible to the naked eye.

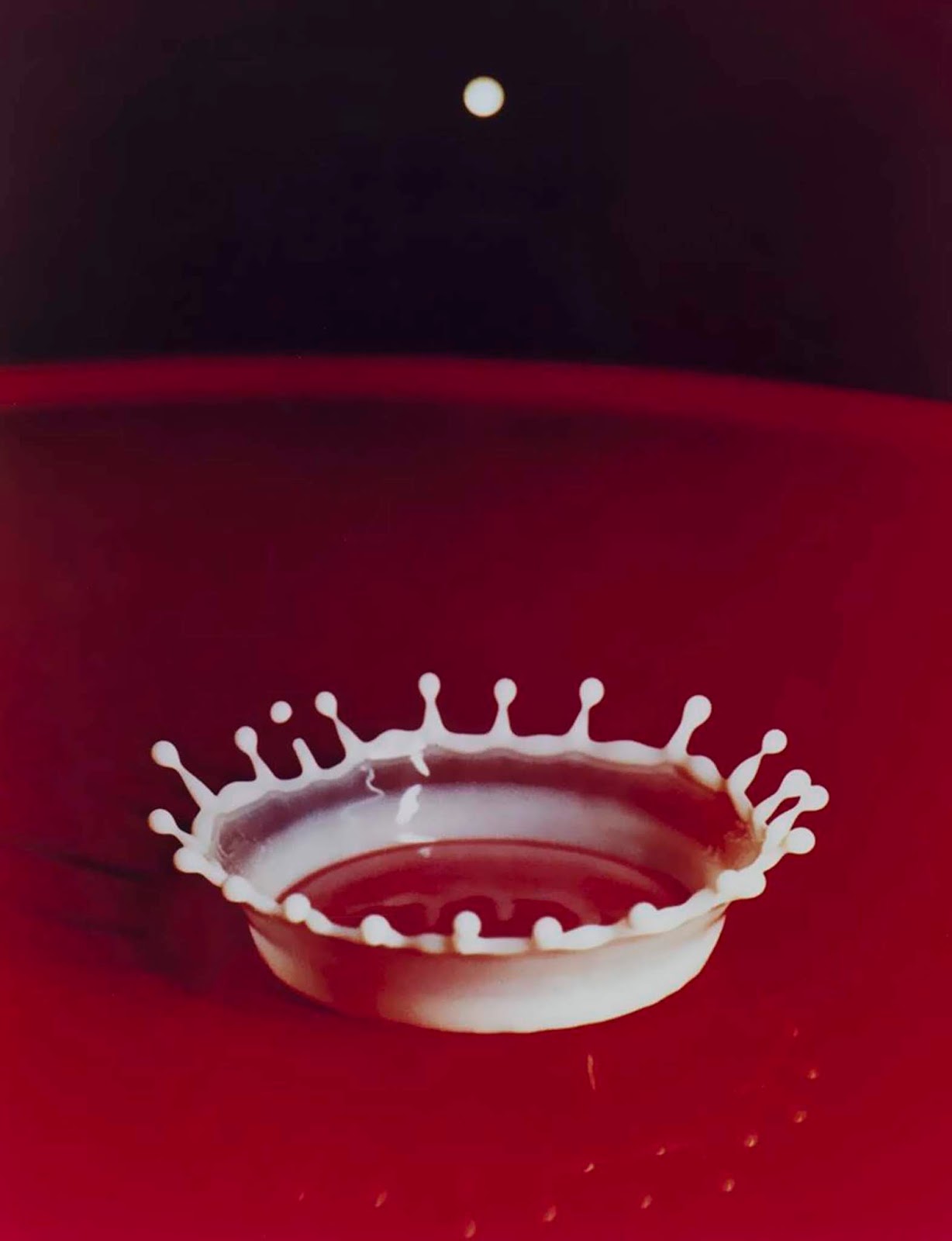

Milk Drop Coronet, his revolutionary stop-motion photograph, freezes the impact of a drop of milk on a table, a crown of liquid discernible to the camera for only a millisecond.

The picture proved that photography could advance human understanding of the physical world, and the technology Edgerton used to take it laid the foundation for the modern electronic flash.

Edgerton worked for years to perfect his milk-drop photographs, many of which were black and white; one version was featured in the first photography exhibition at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art, in 1937.

And while the man known as Doc captured other blink-and-you-missed-it moments, like balloons bursting and a bullet piercing an apple, his milk drop remains a quintessential example of photography’s ability to make art out of evidence.