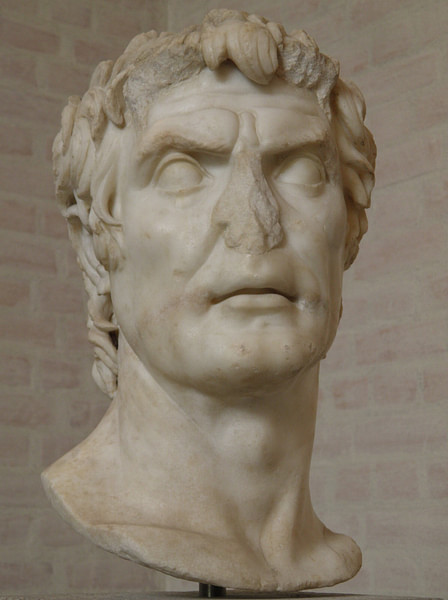

Mithridates VI Eupator of Pontus Carole Raddato (CC BY-SA)

Mithridates VI (120-63 BCE, also known as Mithradates, Mithradates Eupator Dionysius, Mithridates the Great) was the king of Pontus (modern-day northeastern Turkey) who was regarded by his people as their savior from the oppression of Rome and by the Romans as their most formidable – and hated – enemy since Hannibal Barca (247-183 BCE). Like Hannibal, Mithridates proved himself an unstoppable force, defeating Roman armies, manipulating neighboring governments, and even organizing a mass slaughter of Romans and Italians throughout Asia Minor to advance his cause in liberating the region from Roman control.

Mithridates declared himself an enemy of Rome early in his reign and fought three separate wars with the Romans – the so-called Mithridatic Wars – between 89-63 BCE. He eluded capture, made himself immune to poison by ingesting small doses to build up an immunity, and repeatedly won battles against Rome until he was defeated by Pompey the Great (c.70-48 BCE) after betrayal by his son Pharnaces who rose against him. Facing certain defeat and humiliation in a Roman triumph, Mithridates committed suicide.

His story is told almost entirely through the lens of Roman writers such as Plutarch (c. 50 – c. 120 CE) and Appian (c. 95 – c. 165 CE) who were naturally hostile toward him and his cause. Even so, their admiration for his persistence and resolve is clear throughout their narratives, whose focus is not even Mithridates but rather the Romans who fought against him. To the people of his kingdom, as well as those of neighboring regions, he was a great liberator and defender of freedom who refused to submit to what he viewed as the injustice of Roman domination and encouraged others to do likewise.

Early Life & Rise to Power

Mithridates was born in the city of Sinope in Pontus c. 132 BCE. He was the son of the queen Laodice VI (died c. 115 BCE) and the king Mithridates V (150-120 BCE). He was raised in the palace as a Persian prince and seems to have been tutored in languages, military skills, and the arts. He would later claim to be descended from the great kings and conquerors of the past and was well-versed in history. Dr. Adrienne Mayor of Stanford University comments on the meaning of his name and family lineage, writing:

Mithradates (Mith-ra-DAY-tees) is a Persian name meaning “sent by Mithra,” the ancient Iranian sun god. Two variant spellings were used in antiquity – Greek inscriptions favored Mithradates; the Romans preferred Mithridates. As a descendant of Persian royalty and of Alexander the Great, Mithradates saw himself bridging East and West and as a defender of the East against Roman domination. A complex leader of superb intelligence and fierce ambition, Mithradates boldly challenged the late Roman Republic. (1)

Scholar Philip Matyszak challenges Mithridates’ claim of lineage, however, and contradicts Mayor, claiming:

Though Mithridates claimed descent from Darius, king of Persia, and even Alexander the Great, his family probably came from a Persian dynasty from the town of Cius in northern Asia Minor. Mithridates Ctestes (or ‘the founder’) fled from local political troubles in Cius to Pontus, which was then a political backwater under the loose and weakening control of the Seleucid Empire. There he rapidly established a kingdom and a dynasty. (81)

Whatever his actual lineage was, Mithridates purposefully emphasized his descent from Darius and Alexander to link himself directly to a glorious past and give his reign a greater touch of nobility than it would have had otherwise. It may well be that he was, in fact, descended from these earlier leaders but whether he was or not, he would make good use of their names in establishing his own authority.

Mithridates V Mark Cartwright (CC BY-NC-SA)

Such considerations were far ahead of him, however, when his father was assassinated in his palace at Amaseia c. 120 BCE, when Mithridates was only eleven years old. He succeeded his father as the eldest son but was considered too young to rule and so actual power passed to his mother, Laodice VI. Laodice had no choice but to reign as regent surrounded by the men who had poisoned her husband and to accept their counsel in affairs of state.

It would seem that, even at this young age, Mithridates was possessed of a strong will while his younger brother was more pliant. The advisors to the queen, and the queen herself, therefore favored the younger brother for succession because he would be easier to control and plots seem to have been laid for Mithridates’ life. Matyszak writes:

At this time, according to legend, Mithridates started taking homeopathic doses of poison, intending to develop resistance to as many as possible. Feigning an addiction to hunting, he removed himself from the royal center of Amaseia and spent his teenage years in some of the wildest and remotest parts of the country. (82)

Upon his return to the capital c. 116 BCE, Mithridates had his mother and younger brother arrested and purged the palace of all those who were implicated in his father’s death. According to some reports, Laodice and her younger son were executed, but in others, they died in prison. How Mithridates was able to overthrow the nobility of Amaseia and the queen is unknown, but it is probable that, during his time in the wilderness, he was able to win support from the people as a prince forced into exile by a corrupt court.

Although this is speculation, such a course would make sense in light of Mithridates’ later talent for winning large swaths of the populace to his cause. The Roman writers claim that he spent his years in the wilderness alone but he could have well had contacts with supporters in the capital who were able to lay the foundations for his coup. The claim that Mithridates simply emerged from the wilderness one day and toppled the government single-handedly is untenable.

Wars of Conquest & Clash with Rome

Once he had seized power, Mithridates mobilized his army and took the region of Colchis near the Black Sea. He accepted the surrender of a number of cities who appealed to him for help and protection from the Scythians and then conscripted their soldiers into his army. Now with a much larger force, co-commanded by his two generals Diophantus and Neoptolemus, he struck at the Scythians to the north and then the Sarmatians to the west, defeating them and incorporating their warriors into his own forces. He seems to have been widely admired, even by his adversaries. Matyszak writes:

To barbarians who valued physical prowess, Mithridates was a formidable king. He was exceptionally tall, and strong enough to control a sixteen-horse chariot. Until late in life he enjoyed good health, despite being wounded several times. (83)

Throughout this period, Mithridates continued his early interest in homeopathic doses of poison to protect himself from enemies. He eventually created a universal antidote for poison, said to have over 50 ingredients, which was reportedly quite effective. He consolidated his power at Amaseia and instituted reforms in taxation and law, ensuring better lives for his subjects, while also renewing trade agreements with other nations.

Having established control of the regions north and west of his kingdom, he then moved south and established strong diplomatic ties with Armenia, arranging a marriage between his daughter Cleopatra and the Armenian king Tigranes (also known as Tigranes the Great, 95-55 BCE). Tigranes and Mithridates agreed to a separate-but-equal partnership in which they would control different areas and pursue goals which benefited them both without interfering with each other’s plans. Mithridates was trying to gain control of Cappadocia, a region loyal to Rome, and attempted a number of unsuccessful maneuvers to place a puppet king on the throne; when these all failed, he appealed to Tigranes who invaded Cappadocia and conquered it for him.

The Kingdom of Pontus was quickly expanding to become an empire & Rome was far from pleased.

Rome, at this time, had only recently finished its war with Jugurtha in North Africa, was struggling against its Italian allies, and was not interested in another conflict with Pontus. Even so, they could not allow the Armenian conquest of Cappadocia to go unchallenged and sent Lucius Cornelius Sulla (c. 80’s BCE) to restore the former king Ariobarzanes to the throne. The following year, the king of nearby Bithynia, Nicomedes III, died and Mithridates seized upon the opportunity and installed one of his own men on the throne while, simultaneously, invading Cappadocia and toppling Ariobarzanes’ government.

The Kingdom of Pontus was quickly expanding to become an empire and Rome was far from pleased. They sent the consul Manius Aquillius to restore the kingdoms of Bithynia and Cappadocia, and Mithridates, hoping to avoid open war with Rome, withdrew his forces. Aquillius, however, was eager for war with Mithridates, since he was confident of a Roman victory and coveted the wealth of Pontus. His father, of the same name, was known as an especially greedy man who had levied enormous taxes on the people of Asia Minor when he was in charge, and his son seems to have inherited this same avarice.

Aquillius convinced the new king of Bithynia, Nicomedes IV, to attack Pontus and sent advance raiding parties across the border. Mithridates drove these raids back and then attacked Bithynia; initiating war with Rome. Mithridates, now commanding an even larger army than he had before, placed his general Archelaus in command and drove against Bithynia; Aquillius and Nicomedes IV were defeated quickly. According to the ancient sources, Aquillius was then tied to a donkey and paraded through the region as he was forced to confess his crimes and those of his father against the people. He was then executed by Mithridates who had molten gold poured down his throat.

The Asiatic Vespers

Rome had long been in control of much of Asia Minor, and Roman governors and administrators had taxed the people heavily for years. Resentment against Rome was widespread and a hatred of Rome only needed encouragement and a strong leader to fan the embers into a flame and set off a conflagration. Mithridates knew this and so sent word through the region that, on a given date, the people should rise up and murder every Roman and Italian citizen and authority figure in the region.

Mithridates Silver Tetradrachm Mark Cartwright (CC BY-NC-SA)

In 89 or 88 BCE, in a single day, over 80,000 Romans and Italians were massacred. Slaves who murdered their masters were granted freedom, and debtors who killed their Italian or Roman creditors were promised debt relief. The historians Appian and Plutarch both record atrocities in the cities of Adramytium, Caunus, Ephesus, Pergamum, and Tralles but the massacre was widespread and many other cities were involved as well as rural towns and villages.

The number 80,000 is considered a low estimate of casualties, and modern historians place them much higher, probably at 150,000 people killed. Roman writers claim that it was not just resentment toward Rome which encouraged the slaughter but fear of Mithridates and his retaliation for non-compliance. The massacre came to be known as the Asiatic Vespers and was the point of no return in war between the king of Pontus and the Roman Republic.

The Mithridatic Wars

The First Mithridatic War (89-85 BCE) began well for Mithridates as the Romans were only just concluding their struggles against their Italian allies and could not commit a full force to Asia Minor. Further, after the Asiatic Vespers, other regions appealed to Mithridates to help them throw off the yoke of Rome. Greece was among these, and Mithridates obliged by sending a large force under Archelaus to drive the Romans from Athens.

Rome, having finally taken care of the troubles with the Italian states, now sent Sulla at the front of five legions against Mithridates in 87 BCE. Mithridates’ forces had sacked the sacred shrine at Delos and carried away the treasure to pay for mercenaries and Sulla, taking a cue from this, then sacked Delphi to do the same. As Delphi yielded a richer reward, Sulla was able to hire more troops and took Piraeus and then Athens, forcing Archelaus north, and then defeated him in Thessaly. Mithridates was having his own problems with civil unrest at home and, when the war went against him, he negotiated the Peace of Dardanus with Sulla to end the conflict.

Sulla returned to Rome where he declared himself dictator and set about his purges of government positions. One of the results of these purges was to drive a young priest named Gaius Julius Caesar from his office into the army; thus initiating a military and political career famous up to the present day. Mithridates, meanwhile, was repairing his army and consolidating his power when he was attacked by Murena, the Roman governor of Asia, who was afraid Mithridates was going to attack him. This conflict is known as the Second Mithridatic War (83-82 BCE). Murena invaded Pontus at the head of his army but was defeated. Mithridates seems to have then been planning a counterstrike but was ordered to stand down by Sulla and complied.

Sulla Carole Raddato (CC BY-SA)

Mithridates was not going to be so compliant in the future, however, and strengthened his alliance with Tigranes while also entering into agreements with the Cilician pirates, the Ptolemaic Dynasty of Egypt, Thracian tribes, and the rebel slave-leader Spartacus. The idea seems to have been to harass Rome and interfere with trade, not engage in open war, but in 75 or 74 BCE the king Nicomedes IV of Bithynia died and, in his will, left his kingdom to Rome.

This was unacceptable to Mithridates who claimed the will was a fake and installed his own choice as king of Bithynia in defiance of Rome. The Romans requested he remove his choice and, when he refused, declared war. The Third Mithridatic War (73-63 BCE) did not begin as well for Mithridates as the first had. The Roman General Cotta was defeated easily enough, but Lucius Licinius Lucullus (c. 89-66 BCE) proved a more formidable adversary. Lucullus drove Mithridates out of Bithynia and then invaded Pontus. Mithridates was driven back as one fortification after another fell to Lucullus and finally had to flee Pontus for Armenia where he was welcomed at the court of Tigranes.

Lucullus sent word to Tigranes that he should surrender Mithridates and, while he waited for a response, set about restoring the former provinces of Rome. He was aware of the lingering anti-Roman sentiment and, of course, remembered the events of the Asiatic Vespers and so tried to win the people to his cause by lowering taxes and rebuilding cities and towns. C. 69 BCE he finally received an answer from Tigranes saying he would not extradite Mithridates and so Lucullus marched on Armenia. He lay siege to Tigranes’ capital and finally took it, but Tigranes and Mithridates had both escaped. Lucullus was recalled to Rome and replaced by Pompey who began his campaign by destroying Mithridates’ allies, the Cilician pirates.

Betrayal & Death

Tigranes had given Mithridates an army so he could win back his kingdom, and while Pompey was busy dealing with the pirates, Mithridates marched back into Pontus, killed the subordinates Lucullus had left in charge, and regained his throne. Pompey was not one to linger, however, and formed an alliance with the king of Parthia, Phraates III, who swiftly invaded Armenia while Pompey marched on Pontus. Tigranes could no longer help Mithridates who was now driven from his capital and forced into continual retreats as Pompey advanced.

Mithridates was hoping to reach his possessions around the Black Sea and enlist the help of his son Machares, but when he got there, he was disappointed. Machares had aligned himself with Rome and refused his father; so Mithridates killed him. His other son, Pharnaces, then rebelled and led a force against Mithridates as Pompey was closing in. Alone with his two young daughters in a citadel, Mithridates chose to take his own life rather than be captured and paraded in a Roman triumph. After poisoning his daughters, he is said to have tried to poison himself but failed and then asked a slave or servant to kill him.

Crater of Mithridates Eupator Mark Cartwright (CC BY-NC-SA)

Later Roman writers would mock his death, pointing out that the king who had spent a lifetime working with poisons was unable to effectively poison himself. Dr. Mayor has pointed out, however, that Mithridates was said to have always carried enough poison to kill himself if he were ever captured by the Romans but sacrificed at least half of this dose for his daughters (349). Whatever poison was left, then, was not enough for a man of Mithridates’ constitution. The later story of Mithridates having to beg his adversaries to kill him is a Roman fabrication. Pompey recognized the king’s greatness in death and had him buried with full honors in Sinope, the city of his birth.

Conclusion

Although his name is still well known in the East, he never developed the kind of posthumous following in the West as other adversaries of Rome such as Hannibal, Spartacus, or Vercingetorix. The reputation and legend of all three of these men went through a renaissance starting in the 18th century CE and continuing to the present day. All three have now been recast, no matter what their original motivations may have been, as freedom fighters and national champions while Mithridates’ name remains relatively unknown.

Dr. Mayor rightly points out that this is due to pro-Roman historians in the 19th and 20th centuries CE who typecast Mithridates as “a cruel, decadent ‘oriental sultan’, an ‘Asiatic’ enemy of culture and civilization” (7) but it could also be due to the fact that, even without that kind of influence, Mithridates’ story was never embraced by western cultures in the way Hannibal, Spartacus, or Vercingetorix have been because he is a more elusive figure. Unlike the other three mentioned, Mithridates was a king who was also a scientist, a general, a man of culture, a barbarian, a mass-murderer, and a liberator. There is no single label which attaches easily to Mithridates VI in the same way people have recast Spartacus and Vercingetorix as “freedom fighter” and no single image such as Hannibal crossing the Alps. Based on one’s own preconceptions and biases, Mithridates can easily be cast as either a hero or a villain. To those who supported his cause, however, he was an impressive king and liberator who fought to the end against the enemy of his people.

Editorial Review This article has been reviewed by our editorial team before publication to ensure accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards in accordance with our editorial policy.