When Homo sapiens first arrived on the European continent about 42,500 years ago, the Neanderthals were still living there, and would remain there for another 1,400 to 2,900 years before finally disappearing from the face of the Earth. When the anatomically modern humans moved in, the Neanderthals did not move out, but stayed where they were and apparently lived peacefully alongside their Homo sapiens cousins for approximately 2,000 years, give or take a few centuries.

This is the conclusion of a trio of scientists from Leiden University in the Netherlands and Cambridge University in the United Kingdom, who used a unique and sophisticated modeling method known as optimal linear estimation to pin down more exactly when the Neanderthals actually lived in western Europe. The evidence the archaeologists examined was collected from multiple excavation sites in France and northern Spain, where modern human and Neanderthal artifacts have proven relatively easy to find.

Speleofacts ring structure built by Neanderthal people in Bruniquel cave, France. (Luc-Henri Fage/SSAC / CC BY-SA 3.0)

The results of this study, which have just been published in the journal Scientific Reports, offer no evidence to demonstrate that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals merged their genetic materials with each other 42,500 ago. But past research has proven that the modern human genome contains portions of Neanderthal DNA, which could have only gotten there if the two species of hominin had interbred at some point. People of European descent are among those who carry Neanderthal genetic material, so at least some of that interbreeding must have occurred on European soil.

The Stunning Convergence of Modern Humans and Neanderthals

Igor Djakovic, an archaeological PhD candidate at Leiden University and lead author of the Scientific Reports paper, acknowledges in an interview with the French press agency AFP that humans and Neanderthals “met and integrated in Europe,” at some point in the distant past, before adding that “we have no idea in which specific regions this actually happened.”

Scientists have also struggled to identify the precise years when modern humans and Neanderthals would have lived in Europe simultaneously, and this was what the scientists in the Leiden University-led study were trying to discover.

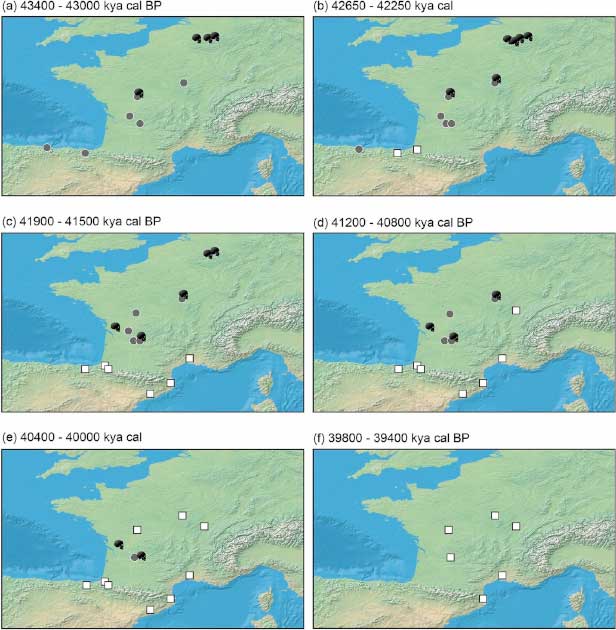

To apply their sophisticated modeling techniques to the question, the scientists gathered radiocarbon dating results connected to 56 artifacts taken from 17 archaeological sites across France and northern Spain. Half of these artifacts had been linked to Neanderthals, while the other half had been left by humans. The artifacts in question included skeletal remains of both species, plus different types of tools including distinctive stone knives believe to have been made by Neanderthals.

Distinctive stone knives thought to have been produced by the last Neanderthals in France and northern Spain. This specific and standardized technology is unknown in the preceding Neanderthal record, and may indicate a diffusion of technological behaviors between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals immediately prior to their disappearance from the region. (Igor Djakovic)

The idea was to cross-reference all of these dated materials, first through Bayesian statistical modeling and then through optimal linear estimation modeling, to search for signs of overlapping activity. Optimal linear estimation modeling is a technique originally developed for use in biology that has now been repurposed for examining and dating human remains and artifacts (and in this case, Neanderthal remains and artifacts as well) to relatively narrow periods of time.

In this study Baynesian modeling could only narrow the potential date ranges down so far, but optimal linear estimation allowed the scientists to achieve much further refinement.

When the final numbers were crunched, the data showed that Neanderthals went extinct in the region of France and northern Spain between 40,870 and 40,547 years ago, a range covering just over three hundred years of time. Meanwhile, it was confirmed that modern humans first migrated into this part of Europe approximately 42,500 years ago. With some variations in the approximate time frame for when the modern humans arrived, the researchers concluded that modern humans and Neanderthals would have occupied the same geographical region for between 1,400 and 2,900 years, after which Neanderthals disappeared forever.

Geographic appearance of dated occurrences for the Châtelperronian (grey circles – Neanderthal stone tools), Protoaurignacian (white squares – Homo sapiens stone tools), and directly-dated Neandertals (black skulls) in the study region between 43,400 (a) and 39,400 (f) years cal BP. (Djakovic, I., Key, A. & M. Soressi / Nature 2022)

Sharing Knowledge

While there is no proof, it is reasonable to conclude that interbreeding between the two genetically compatible species would have occurred at this time and at this place. Perhaps just as significantly, there are signs that an extensive “diffusion of ideas” occurred, according to Djakovic, meaning there was a meeting of the cultures and a meeting of the minds that accompanied the physical encounters.

This period of time is “associated with substantial transformations in the way that people are producing material culture,” including the way they made tools and ornaments, Djakovic explained. He and his colleagues also noted a dramatic change in the types of physical artifacts being produced by Neanderthals, which started to closely resemble tools and utensils made by the modern humans.

The Death of the Neanderthals Has Been Greatly Exaggerated

The latest research reveals that the DNA of humans of European and Asian descent is between one and two percent Neanderthal. In Africans Neanderthal DNA is not found except in trace amounts, since Africans and Neanderthals did not come into contact before the latter went extinct.

With respect to the extinction of the Neanderthals, Igor Djakovic argues that the concept should be reconsidered.

“When you combine that with what we know now—that most people living on Earth have Neanderthal DNA—you could make the argument that they never really went extinct, in a certain sense,” Djakovic said. Instead, he hypothesized, they were “effectively swallowed into our gene pool,” where they continue to exert a small but real influence over human genetic development to this very day.

It remains a mystery why Neanderthals weren’t able to breed and produce enough offspring among themselves to preserve their viability as a distinct species after modern human contact. Many different theories have been offered, but none are universally accepted.

Nevertheless, through genetic exchanges with anatomically modern humans they were able to guarantee their survival in a different form. They are like a shadow inside us, still preserved and never to be completely forgotten.