Long dismissed for being our brutish ancestors, we share more with Neanderthals than we think, and increasingly research is showing us just how much there is in common. Scientists have run computer simulations that have revealed vital information about the evolution of large, broad Neanderthal noses.

These noses have displayed the ability to regulate the cold, dry air of the Ice Age, and meeting high oxygen demand of our ancient cousins (as discovered in a 2018 study). They show that this unique shape survived through inter-species reproduction, currently existing in certain modern humans. The distinctive nose structure influenced its height and length, enduring tens of thousands of years of natural selection before being detected in present times.

Rendering of a face representing Neanderthal features. (nicolasprimola/Adobe Stock)

A Broad Sample Size and Base

The findings of this landmark study, a follow up to a 2021 study about genes determining face shapes, have been published in the journal Communications Biology. The interdisciplinary team from across the world studied the genetic information of and from 6,000 modern humans of mixed European, Native American, and African ancestry from Latin America.

Co-corresponding author Professor Andres Ruiz-Linares from Fudan University, UCL Genetics, Evolution & Environment, and Aix-Marseille University explained in a press release:

“Most genetic studies of human diversity have investigated the genes of Europeans; our study’s diverse sample of Latin American participants broadens the reach of genetic study findings, helping us to better understand the genetics of all humans.”

These findings were then cross-referenced with the measurements of the facial features of the individuals, especially their noses and the tips of their lips. Utilizing advanced software, the research team from the University College London identified 106 facial landmarks encompassing regions such as the eyes, nose, mouth, temples, and chin.

“Different shaped noses may be better suited to different climates that our ancestors lived in,” added lead author Qing Li of Fudan University. “The gene we have identified here may have been inherited from Neanderthals to help humans adapt to colder climates as our ancestors moved out of Africa.”

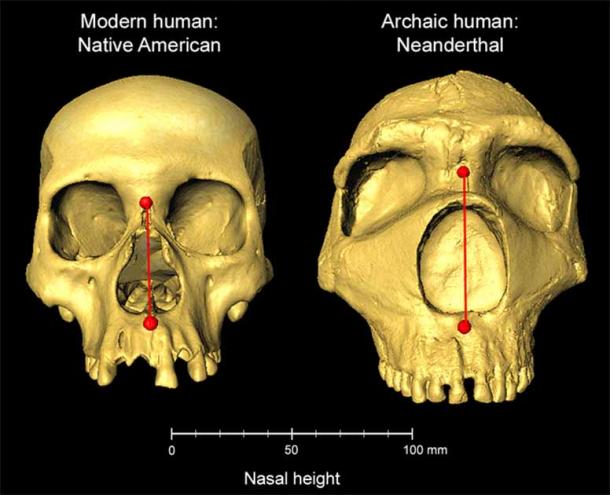

Modern human and archaic Neanderthal skulls side by side, showing difference in nasal height. (Dr Kaustubh Adhikari, UCL/ Nature)

Neanderthals and Modern Humans: Closer than Imagined

The close genetic relationship between humans and Neanderthals has been established since the sequencing of the first Neanderthal genome in 2010, revealing a shared ancestral lineage. This connection allowed genetic traits to be passed down, maintaining the ancient bond between the two species.

Neanderthals were highly sociable and intelligent, physically shorter than moder humans, and had barrel chests and pronounced brows. Numerous studies have shown that their bodies were built for endurance.

In an important discovery made last June, scientists unveiled a specific genetic variation that can be traced back to a single interbreeding event with Neanderthals. This genetic tweak has been found to double the risk of severe Covid-19 in individuals who carry it today.

Neanderthals, who existed as a distinct human species, have contributed approximately 1 to 4 percent of the genomes of non-African modern humans. However, it is assumed that individuals of African descent from regions south of the Sahara have no detectable Neanderthal DNA in their genetic makeup.

Sequencing DNA: The Inheritance of Loss

Dr Kaustubh Adhikari, who co-led the study, explained:

“In the last 15 years, since the Neanderthal genome has been sequenced, we have been able to learn that our own ancestors apparently interbred with Neanderthals, leaving us with little bits of their DNA. Here, we find that some DNA inherited from Neanderthals influences the shape of our faces.”

The study uncovered 33 genome regions that correlated with facial features, including a Neanderthal-derived region named ATF3, responsible for the development of longer noses. The aforementioned study in 2021 had expanded on this research, identifying 32 modern gene regions associated with facial characteristics among the same 6,000 participants, including nine novel discoveries.

The researchers found that many people in their study with Native American ancestry (as well as others with east Asian ancestry from another group), exhibited this gene. An even earlier study had found that the expression of ATF3 is regulated by another transcription factor, FOXL2, mutations of which “are known to lead to alterations of the midface.”

These findings included a gene called TBX15, linked to the ancient Denisovan people who inhabited Central Asia and interbred with early Homo sapiens. Interestingly, not all individuals possess this gene sequence, suggesting its potential role in better adapting to the cold climates of Central Asia through body fat distribution, reports Discover Magazine.

Andres Ruiz-Linares, a professor at Fudan University concluded that, “research like this can provide basic biomedical insights and help us understand how humans evolved.” Indeed, 40,000 years later, remnants of our lost relatives live on in earnest in our gene pool.