Researchers have announced the discovery of bone tools in a cave in Morocco that appear to have been used to carefully remove skins and fur from the bodies of dead animals. The skins recovered this way were apparently used to make clothing.

Such a find would not normally be considered remarkable. But these particular tools are approximately 120,000 years old, which pushes the timeframe for clothes-making practices farther back into the past than scientists would have once believed was possible.

“These bone tools have shaping and use marks that indicate they were used for scraping hides to make leather and for scraping pelts to make fur,” anthropologist and research team leader Dr. Emily Hallett explained in a press release from science journal publisher Cell Press.

“At the same time, I found a pattern of cut marks on the carnivore bones from Contrebandiers Cave that suggested that humans were not processing carnivores for meat but were instead skinning them for their fur.”

The ancient fur and leather makers were early Homo Sapiens (modern humans), who at this point had yet to leave Africa to explore and colonize the rest of the planet. Even before the original great migration that scattered their populations across the globe, the earliest humans were showing a surprisingly sophisticated range of behaviors.

“Our study adds another piece to the long list of hallmark human behaviors that begin to appear in the archaeological record of Africa around 100,000 years ago,” stated Dr. Hallett, who along with most of the scientists involved in this research project is affiliated with the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany.

The Contrabandiers Cave site, Morocco (The Guardian)

Researchers don’t expect to find actual clothing samples during excavations at Contrebandiers Cave. Leather and fur clothing would be too delicate to be preserved for more than 100,000 years.

But fascinating studies of the DNA of clothing lice have shown that they likely evolved from human head lice somewhere between 83,000 and 170,000 years ago. This takes their origin back to the time when modern humans were still living exclusively Africa, offering further evidence that people have been making clothes for a very long time.

The Tools Tell the Tale

As they explain in an article detailing their discoveries in the journal iScience, Dr. Hallett and her colleagues closely examined the remains of animal bones excavated over several decades from Contrebandiers Cave on Morocco’s Atlantic coast. These bones had been unearthed in layers dating back to between 120,000 and 90,000 BC, and had been found alongside the skeletal remains of humans who were using the cave throughout that time period.

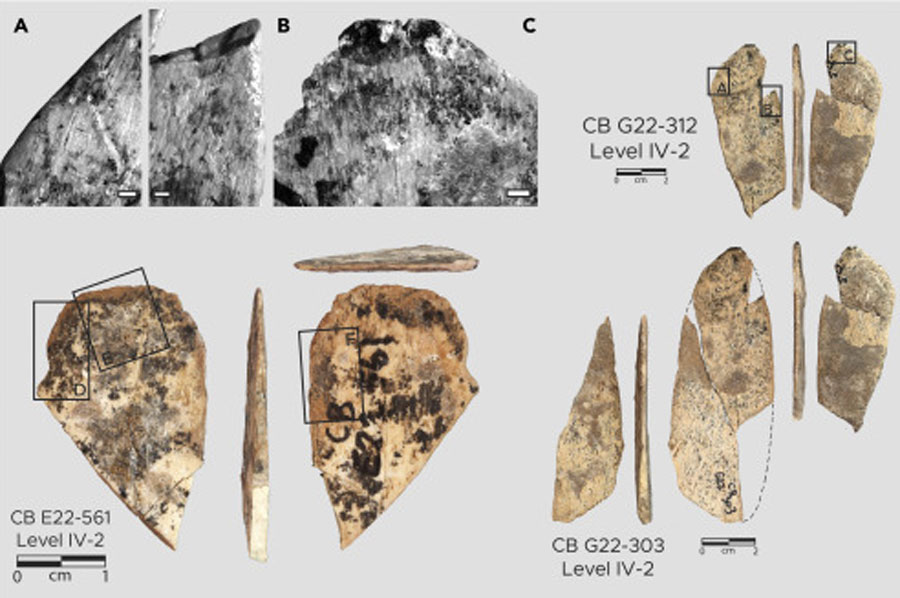

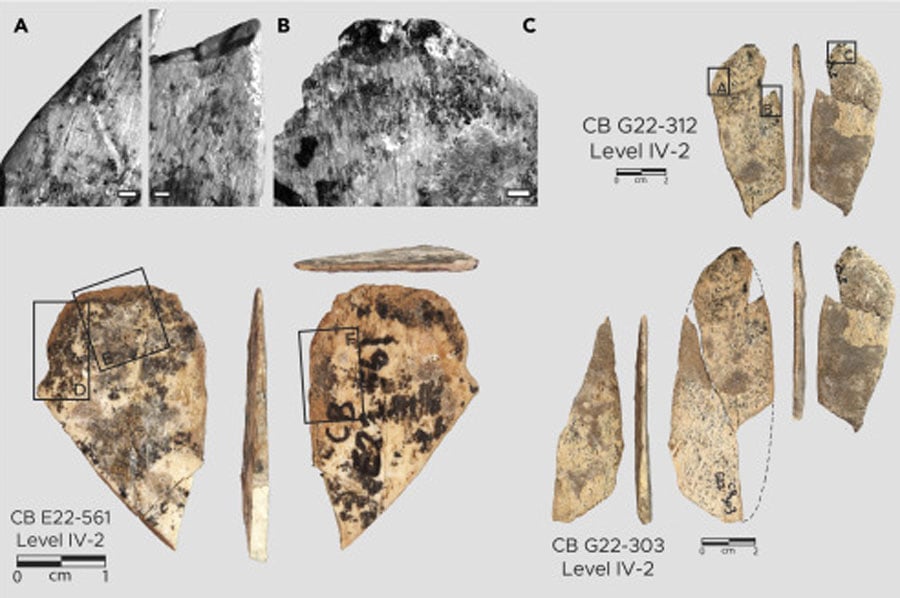

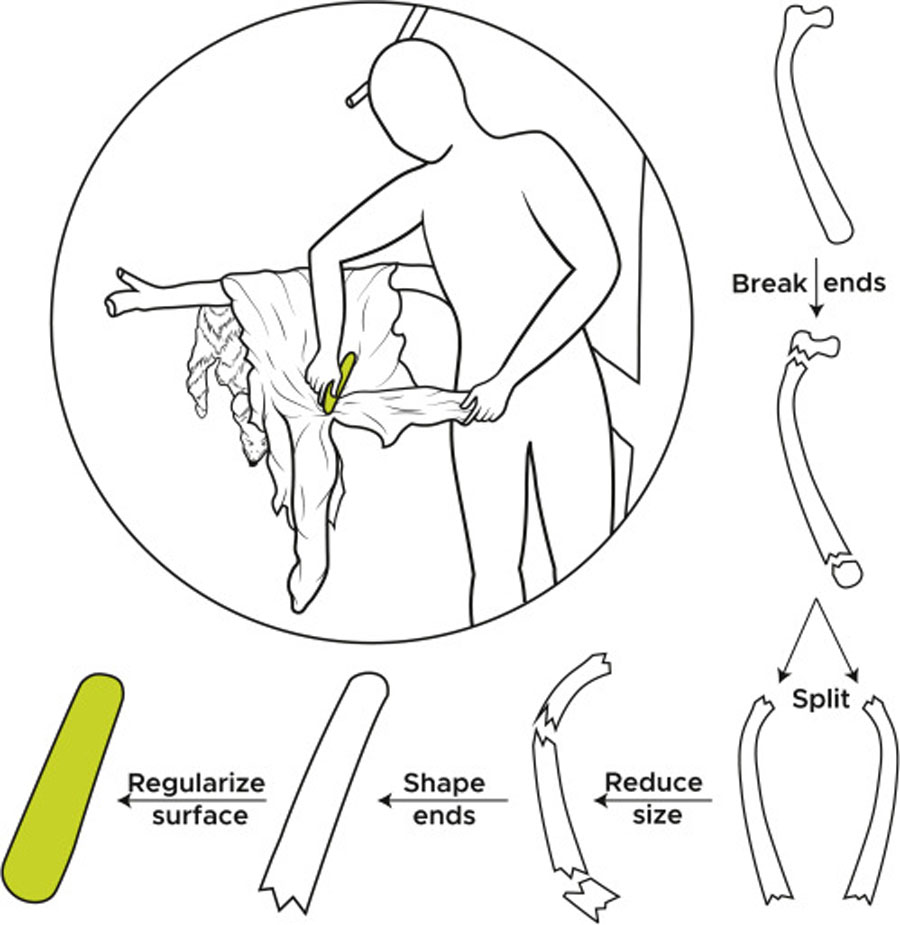

Some of the animal bones (62 to be exact) had clearly been fashioned into tools of various kinds, and one type of tool in particular caught their attention. These sturdy objects were made from the rib bones of cattle, and had been rounded into the shape of a spatula on one end.

“Spatulate-shaped tools are ideal for scraping and thus removing internal connective tissues from leathers and pelts during the hide or fur-working process, as they do not pierce the skin or pelt,” the researchers wrote in their iScience article.

Skinned fox bones with evidence of scraping (Cell Press)

A few of the bones Dr. Hallett and her colleagues looked at hadn’t been made into tools at all. But they contained telltale scraping marks showing that attached skin and fur had been thoroughly and carefully removed. It is notable that the bones that contained such markings came from species that likely would have possessed thick coats of fur, including ancient versions of foxes, wildcats, and jackals.

Dr. Hallett found other marked bones that came from species similar to modern cattle. But in these cases, the cuts and scrapings had different characteristics. These marks were of a type that would be caused if meat were being deboned, in preparation for it to be used as food.

One other intriguing discovery found at the cave was a whale’s tooth, which had been partially modified and was likely used to flake stone. Dating to the same 120,000 to 90,000 BC period, this is the oldest tool made from marine mammal bone that has ever been found during an archaeological excavation, anywhere in the world. Nothing of its kind from any time period had ever been found in northern Africa before, Dr. Hallett confirmed.

Prehistoric Humans Were Doing It, and Neanderthals Were Doing It, Too

Dr. Hallett doesn’t think modern humans were the only hominin species to discover the benefits of clothes-making. She believes that European Neanderthals were making clothing from animal skins and furs before modern humans arrived in the region, most likely approximately 40,000 years ago.

Evidence is available that supports this theory. In 2013, archaeologists discovered a particular type of leatherworking tool known as a lissoir during excavations at two caves (Abri Peyrony and Pech-de-l’Azé) in southwestern France. These caves were once occupied by Neanderthals rather than humans, and that the tools in question had apparently been manufactured around 50,000 BC.

Commenting on the latest findings in Morocco, Dr. Matt Pope, an archaeologist from University College London, told the Guardian that these ancient humans must have been accomplished leatherworkers.

“This is an adaptation which goes beyond just the adoption of clothing,” he said. “It allows us to imagine clothing which is more waterproof, closer-fitting and easier to move in, than more simple scraped hides.”

How the tools were fashioned and used (Cell Press)

Dr. Pope noted that well-processed leather could have also been used to make containers, windbreaks, shelters, and many other useful products. Since Neanderthals were using similar sophisticated tools in Europe, he theorized, they must have been quite skilled at making leather products of various types as well.

Dr. Hallett is curious to see if other archaeologists exploring human-occupied caves elsewhere in Africa will find similar evidence of ancient clothes-making practices. Now that they know such evidence exists, they will know what to look for and won’t dismiss findings that push the clothes-making timeline back even deeper into prehistory.