A team of scientists from the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), in collaboration with colleagues from several scientific institutions in Germany, have just published a new study of Neanderthal dietary practices in the journal PNAS. Applying a newly developed technique for studying the chemical signatures of ancient tooth enamel, they’ve been able to determine that a Neanderthal living in a cave on the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Paleolithic period (50,000 years ago) consumed a strictly carnivorous diet.

This is not the first study to return such a finding. It is nevertheless a unique and important discovery, since it resulted from the creation of a fresh analytical methodology that could be used to search for details about the diet and lifestyle of Neanderthals who lived elsewhere in Eurasia in the remote past.

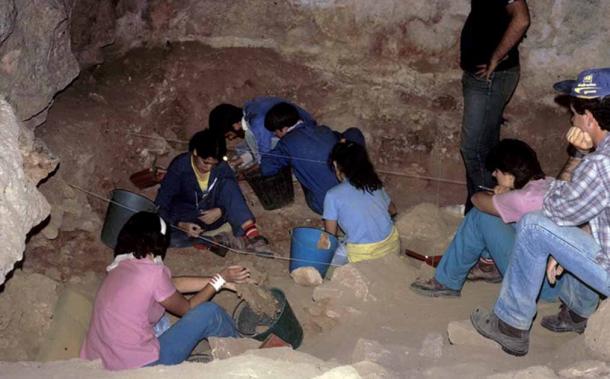

Excavation work at the Gabasa site, Spain, unearthed a tooth which was the basis for the study of the Neanderthal diet. (© Lourdes Montes / CNRS)

Unraveling the Enigma of the Neanderthal Diet

Many research projects have been launched to study Neanderthal diet and eating habits. But they have produced conflicting results. ‘Neanderthals’ diets are a topic of continued debate, especially since their disappearance has been frequently attributed to their subsistence strategy,” the CNRS scientists wrote in their PNAS paper. “There is no clear consensus on how variable their diets were in time and space.”

As the CNRS researchers acknowledge, conventional testing of nitrogen isotope ratios has generally supported the notion the Neanderthal diet was exclusively carnivore. However, there have been a few studies that show clear indications that at least some Neanderthals were omnivorous.

For example, there was a 2014 study published in Science that analyzed fossilized Neanderthal excrement found at the El Salt site in Alicante in southern Spain. This 50,000-year-old poop contained cholesterol-related compounds that came from plant-based food sources exclusively.

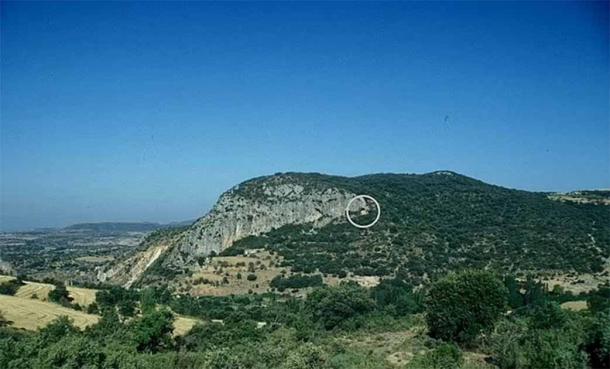

The Neanderthal tooth used in the study was recovered from the Gabasa Cave (signaled in the image) in northeast Spain was used to provide evidence about the Neanderthal diet. (© Lourdes Montes / CNRS)

Zinc Isotope Ratios Provide Evidence for Neanderthal Diet

The traditional method for determining an ancient hominin diet requires the extraction of proteins from bone collagen. These proteins contain nitrogen isotopes, which act as a chemical signal that can be linked to the dietary choices of that particular individual.

In this newest study, the CNRS scientists and their German associates examined a Neanderthal molar recovered from the Gabasa Cave archaeological site in northern Spain. They followed the same basic outline of the normal research protocols, but in this instance CNRS researcher Klevia Jaouen and her colleagues substituted measurements of zinc isotope ratios for those of nitrogen isotopes.

Further modifying the procedure, they took these measurements not from samples of bone collagen, but from the tooth’s enamel coating. This outer layer of the hominin tooth is made from calcium phosphate, a super-hard mineral that is resistant to decay and degradation. Enamel creation is also impacted by dietary choices, and zinc isotope ratios measured inside of enamel offer intriguing possibilities for uncovering what a Neanderthal would have been eating thousands of years ago.

A first molar from a Neanderthal, analyzed for this study, was used to provide information about the Neanderthal diet. (© Lourdes Montes / CNRS)

Groundbreaking Attempt to Track Neanderthal Diet

Such a method for tracking a long-deceased Neanderthal’s dietary preferences had never been attempted before. But the CNRS researchers knew that a carnivorous diet should produce relatively low proportions of zinc isotopes in the teeth and bones, and that was exactly what they found in their analysis of the Middle Paleolithic molar.

For comparative purposes, they used the same methodology to study zinc isotope ratios in the recovered teeth and bones of both herbivorous and carnivorous animals from the same area and time period. The results of all the tests showed that the Neanderthal owner of the tooth must have been a dedicated meat eater who didn’t supplement their diet with any type of fruit or vegetable.

Broken animal bones found in the same excavation layer that produced the molar suggest this individual did eat bone marrow in addition to meat, but beyond that there is no indication of any other food having been consumed. Now that zinc isotope analysis has proven its mettle, the scientists involved in this study plan to use it to analyze the bones and teeth of Neanderthals found at other European sites.

Conclusions on Neanderthal Diets

Neanderthals may in fact have preferred a carnivorous diet. But some groups could have been forced by geographical, ecological, or climatological circumstances to adapt their diets to the landscapes they were occupying. It’s also possible that Neanderthal culture was inherently diverse, leading some groups to choose an omnivorous diet simply because they could.

While archaeologists and anthropologists have been able to draw some firm conclusions about the Neanderthal lifestyle, significant elements of mystery remain. Even if final answers prove difficult to obtain, each new discovery of Neanderthal artifacts and remains—and each re-analysis of past discoveries using the most up-to-date scientific tools—adds valuable new data points that will help scientists put a few more pieces of this intricate puzzle together.

Since most humans carry between one and two percent Neanderthal DNA inside their genomes, the study of Neanderthals is quite literally a search for the truth about our ancestors.