The Northrop XB-35 stands as a testament to the audacious spirit of innovation that defined the aviation industry during the early 1940s.

Developed by Northrop Corporation in collaboration with the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF), the XB-35 was an experimental aircraft that pushed the boundaries of aeronautical engineering.

With its revolutionary flying wing design, impressive payload capacity, and ambitious goals, the XB-35 aimed to revolutionize long-range strategic bombing.

At the core of the XB-35’s groundbreaking design was its flying wing configuration. This unconventional approach seamlessly integrated the wing and fuselage, eliminating the need for a separate tail assembly.

The absence of a traditional tail section allowed for enhanced stability, reduced drag, and increased lift, ultimately leading to improved performance and fuel efficiency.

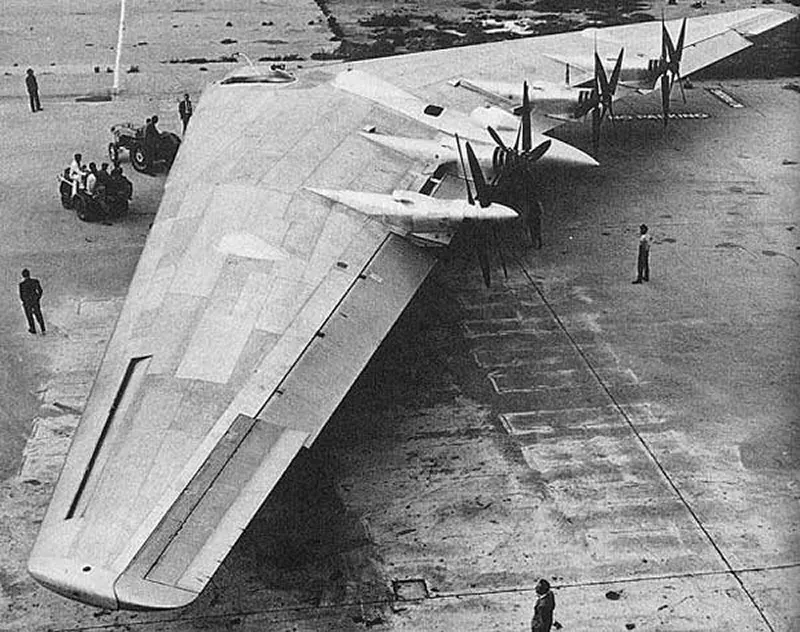

YB-35 prototype.

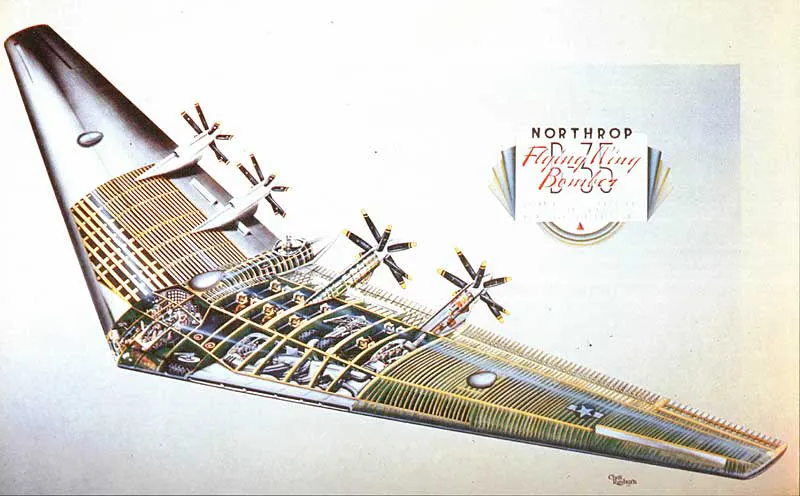

Detailed engineering began in early 1942. A fuselage-like crew cabin was to be embedded inside the wing; it included a tail cone protruding from the trailing edge.

This tail cone would contain the remote sighting stations for the bomber’s gunners and a cluster of rear-firing machine guns in the production aircraft. In the midsection of the cabin, there were folding bunks for off-duty crew on long missions.

The aircraft’s bomb load was to be carried in six smaller bomb bays, three in each wing section, fitted with roll-away doors; this original design precluded the carrying of large bombs, and the early atomic bombs, without bomb bay redesign and modifications.

YB-35 Flying Wing showing its quartet of pusher contra-rotating propellers. The option was later discarded due to severe vibration in flight and later changed to the traditional single propeller configuration.

The XB-35 and YB-35, driven by four rear-facing propellors, were flown with moderate success.

Actual flight tests of the aircraft revealed several problems: the contra-rotating props caused constant heavy drive-shaft vibration and the government-supplied gearboxes had frequent malfunctions and reduced the effectiveness of propeller control.

After only 19 flights, Northrop grounded the first XB-35; the second aircraft was grounded after eight test flights.

In the end, the program was terminated due to its technical difficulties and the obsolescence of its reciprocating propeller engines, and the fact it was far behind schedule and over budget.

Another contributing factor to the program’s failure was the tendency of Northrop to become engaged in many experimental programs, which spread its small engineering staff far too wide.

While the competing propeller-driven B-36 was obsolete by that time and had just as many or even more development problems, the Air Force needed a very long-range, post-war atomic bomber to counter the perceived Soviet threat.

Northrop’s XB-35 Flying Wing Bomber is wheeled on to the runway for its first taxi tests in Hawthorne, California.

There are long-standing conspiracy theories about the cancellation of the Flying Wing program; specifically, an accusation from Jack Northrop that Secretary of the Air Force Stuart Symington attempted to coerce him to merge his company with the Atlas Corporation-controlled Convair.

In a 1979 taped interview, Jack Northrop claimed the Flying Wing contract was cancelled because he would not agree to a merger because Convair’s merger demands were “grossly unfair to Northrop.”

When Northrop refused, Symington supposedly arranged to cancel the B-35 and B-49 program. Symington became president of Convair after he left government service a short time later.

Other observers note that the B-35 and B-49 designs had well-documented performance and design issues while the Convair B-36 needed more development money.

A crowd watches as the XB-35 takes off on its maiden flight.

The XB-35’s legacy extends beyond its technological advancements. It symbolizes the spirit of exploration and the pursuit of excellence that has propelled the aviation industry forward.

The audacity and vision of the engineers and designers involved in the XB-35 program continue to inspire generations of aviation enthusiasts, reminding us of the remarkable achievements made possible through human ingenuity.

The concept was revisited in the 1980s, as the flying wing’s sleek profile made it less likely to reflect radar waves.

This insight, along with advances in electronic stabilization, led to the creation of the now iconic B-2 Spirit stealth bomber.

A Northrop YB-49 takes off on a test flight in California.

A Northrop YB-49.

The Northrop factory in Hawthorne, California.

A Northrop YB-49 in flight.

This is a rare photo of nine Northrop Flying Wing Bombers. Many people do not realize that more than one or two prototypes were built of this design. Here, for the first time, is actual proof of their existence. Two of the big wing bombers are undergoing modifications from XB-35’s to Flying Wing B-49 1t Bombers. (Photo by century-of-flight.freeola.com)

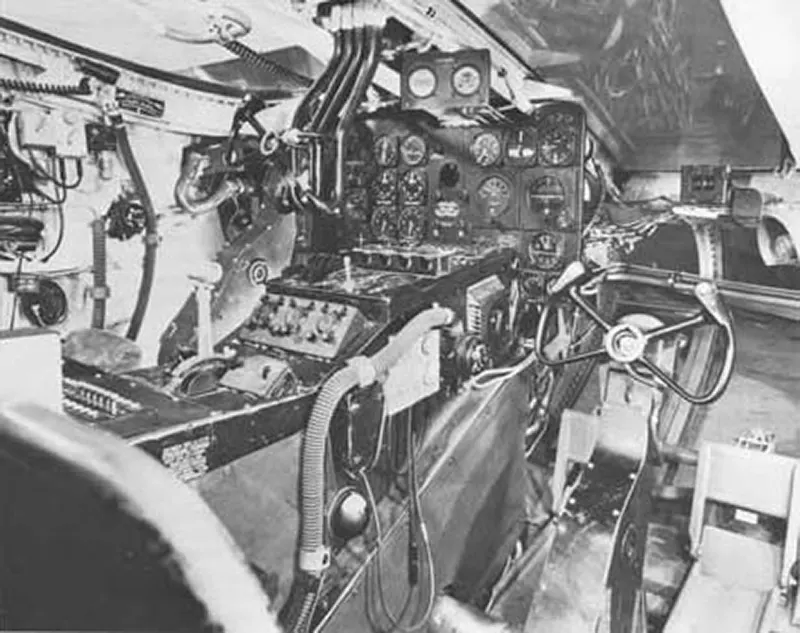

The cockpit.

Northrop XB-35 Cutaway.

Northrop XB-35 Flying wing, a heavy bomber prototype.

Regardless of developmental problems, the Flying Wing in the air was the epitome of style and grace, exhibiting an extraordinary quality that caught the fancy and imagination of the public.