In one fell swoop, 22-year-old Olga Hepnarová killed eight people and injured dozens more in Prague. Here’s her chilling story.

One summer day in 1973, a large group of elderly people were waiting at a Prague tram stop for their morning ride. Around 11 AM, a pick-up truck suddenly came hurtling down the road, swerved violently onto the pavement and slammed into them.

Screams filled the air, dead bodies lined the streets, and a few meters down the road, sitting calmly in the driver’s seat, was the 22-year-old girl who had decided to kill them all.

Olga Hepnarová. Still from Aktualne TV.

Olga Hepnarová is one of Europe’s most prolific and least known mass murderesses. Her heinous crime — an almost unrivaled example of vehicular homicide — took the lives of eight people and injured a dozen more.

While sickening in its method of execution, it was the cold, premeditated way in which it was all planned that is perhaps most shocking of all.

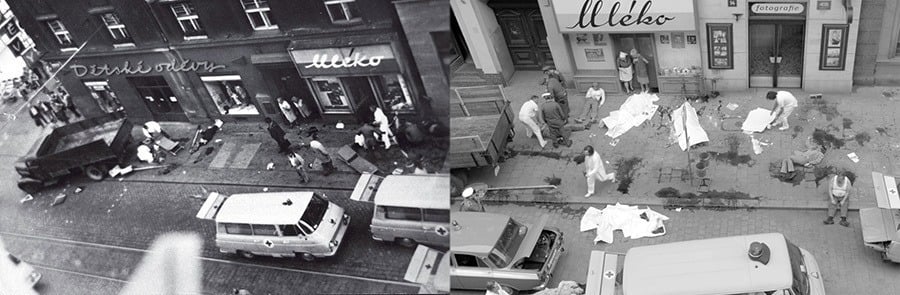

The truck Hepnarová used to commit her crime.

Riddled with psychological problems and fueled by an intense hatred of humanity, the young truck driver decided to enact a monumental act of revenge upon the world. Detailing her motives in letters she delivered to two Czech newspapers two days prior to the murders, Hepnarová stated:

“I am a loner. A destroyed woman. A woman destroyed by people… I have a choice — to kill myself or to kill others. My verdict is: I, Olga Hepnarová, the victim of your bestiality, sentence you to death.”

This self-appointed form of “sentencing” led to a sentencing of her own — death by hanging. Two years later, she was executed by short-drop hanging, thus becoming the last ever woman to be hanged in then-Czechoslovakia, and one of the last in Europe.

Her darkly fascinating story is the subject of an acclaimed new film, Já, Olga Hepnarová, directed by Tomas Weinreb and Petr Kazda. Though the film documents the cold-blooded murder, it also carves its way into the recesses of Hepnarová’s complicated psyche.

Olga Hepnarová, as she appears in the feature-length film Já, Olga Hepnarová.

“She wasn’t a werewolf or a fantastic monster,” Weinreb said. “She was a human. In her life, we saw the story of an outcast, of a person that just did not fit into society. Loneliness and hate finally led to the horrifying act of violence – and that was the story we wanted to tell.”

This story, shot in ominous black and white, begins with Hepnarová’s suicide attempt at the age of 13. The attempt, made by taking a handful of the drug Meprobamate, was a culmination of the bullying that she felt she was being subjected to by her classmates.

What followed were long stints of incarceration at a child’s psychiatric clinic in Opařany. During these times, doctors identified a number of unhealthy traits — apathy, insubordination, negativism, detachment, vomiting, and nicotine addiction — but were unable to offer a complete diagnosis of Hepnarová’s illness.

One psychiatrist, one of the few people Olga Hepnarová actually opened up to, eventually diagnosed her with schizophrenia. Two years later, in 1967, a week before her 16th birthday, she wrote him a letter, updating him about her state of mind.

She told him that she hadn’t spoken to her father since her last beating, and that she now had nothing to talk about with her mother. She then expressed her view on society in general, writing:

“I hate people. I wonder how my relationship will look as time goes by. I want the people to not exist for me at all, their words and chatter are indifferent to me. That’s what I want. It’s better for me when I’m alone than when I’m with them…Everyone falls for their smiles and fellowship. They mutilated my soul.”

After leaving the hospital and failing to hold down a number of jobs, Hepnarová retired to a cottage in the Czech countryside and got a job working as a truck driver. During this time, her sexual appetite was awakened, and she formed a number of relationships with women — conveyed in the movie by an array of highly-explicit sex scenes.

Olga’s sexual awakening is also depicted in the film.

“She was not just a lesbian,” says Kazda, however. “It would be far too simple to brand her like that. She had relationships with men and women, and she described reaching orgasm with men too. She tended towards women, yes. But she shouldn´t be labeled as a ‘lesbian killer’ or something like that.”

The film, in fact, shows her enjoying a lengthy relationship with an older man, Miroslav, and it was him with whom she spent a long, camping holiday, just before committing her crime.

The crime itself was a cold and calculated one.

Having written the letters to the newspapers (the letters were only opened after the act), she rented a truck and drove to a busy, residential spot in Prague called Strossmayerovo Namesti. The tram stop was a busy one, located at the bottom of a hill, and according to her, allowed a good run-up in order to get maximum impact.

When she initially drove toward it, she changed her mind. Not because of nerves or because she’d had a change of heart; it was because she had felt that the number of people waiting there was too few. After driving around the block and resuming her position, she then tried again.

This time Olga Hepnarová drove with intent, mounting the pavement around 30 meters from the tram stop, and accelerating rapidly into the group of people waiting there. She collided with 20 of them, careened into a number of shops, then stopped at the end of the street. After this, she simply sat and waited for the police.

The crime scene of Olga Hepnarová’s murders.

The collision killed three people instantly, a further five died later in hospital and 12 others sustained other injuries. All of them were elderly.

After the act, Hepnarová showed a complete lack of remorse, repeatedly pleading guilty to her crime and asking during her subsequent trial that she be given the death penalty. Two years later, on March 12, 1975, she was executed.

“She felt to be totally misunderstood by society,” says Kazda. “She wrote about how she was expelled from society, bullied as a teenager and put in the psychiatric hospital by her family.”

“Forty years ago, society did not know how to treat people with the psychological problems that she had,” adds Weinreb. “You were just strange, and others treated you as a stranger. Back at the time of her trial there was either 15 years in prison at most as an appropriate punishment or the death penalty. It was not possible to serve a lifetime. And 15 years in prison just did not seem to be enough for the horror she had done.”