American paratroopers attached to Operation Varsity may have missed their drop zone but not their opportunity in March 1945, weeks before war’s end in Europe

The morning sky was gray on Saturday, March 24, 1945, when paratroopers of the U.S. 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment’s 1st Battalion started gearing up. The Allied airfield in France, designated A-40, was packed with rows of twin-engine C-47 cargo planes.

At each aircraft the men had divided into pairs for the practiced ritual of donning their parachutes. The ordinarily straightforward process was complicated by having to route the harnesses around canteens, shovels, medical aid bags, map cases, demolition packs and firearms of all sorts, mostly rifles, submachine guns and carbines.

As they shrugged on their equipment, their commander, Col. Edson Raff, drove up the flight line. He stopped at each cluster of troopers to stand in his jeep and deliver a short but direct sermon: “Give the goddamned bastards hell, men! You know what to do. Cut out their goddamned guts!”

Raff had the personality and résumé to back up his bravado. The tough 37-year-old West Point graduate was an ardent believer in strong leadership and had commanded the Americans’ first combat jump into North Africa as well as battled through the bocage in France. As a result of those experiences he embraced the brutality of his profession. “Forget good sportsmanshipon the battlefield,” he wrote in his wartime memoir. “And if for one moment you feel soft toward that Nazi shooting at you, remember he’s trying to kill you, and if he had the chance, he’d drive your dad into slavery, cut your mother’s throat and rape your wife, sister, sweetheart or daughter. You’ll get no quarter from him. Give him none!”

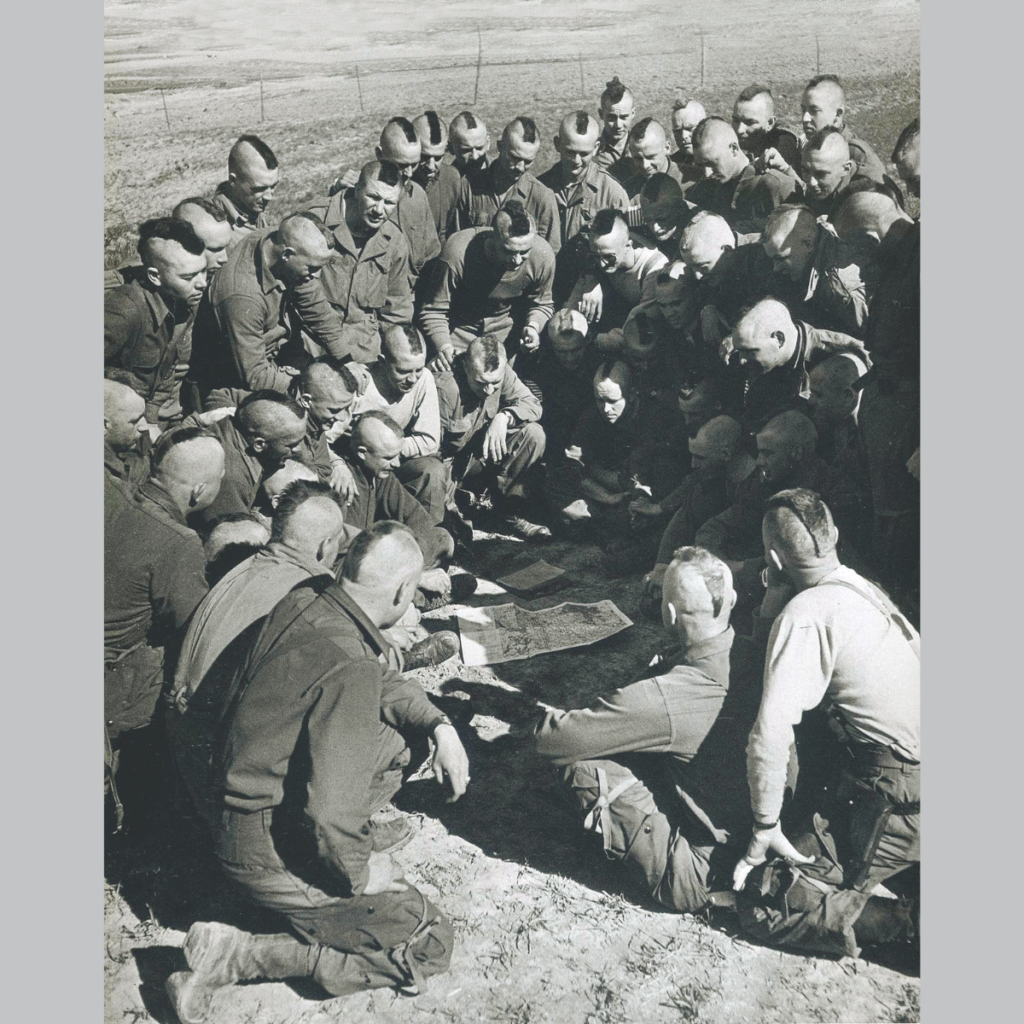

Raff had taken command of the 507th in June 1944 after the Germans captured the original commander a few days into the Normandy campaign. The outsider’s assignment disgruntled the regiment’s rank and file, and his popularity dropped even more when he introduced the men to his combat maxims on their withdrawal back to England. One of his favorites, “The squad and platoon must be perfectly trained—they win battles,” was perhaps his men’s least favorite.

His focus on the smallest unit in the Army’s inventory was often mistaken for micromanagement. And despite needing a training regimen to incorporate newly arrived replacements, many of the Normandy veterans took offense to Raff’s back-to-basics emphasis on fundamental field tactics. His physical training regime was disliked as well. Raff liked to exercise—a lot.

In August 1944 the 507th was transferred out of the 82nd Airborne Division and attached to the untested 17th Airborne Division, a move that further reduced Raff’s limited popularity. His aggressive attitude and diminutive height of 5 feet 6 inches earned him the nickname “Little Caesar.”

Captain Chester McCoid, an intelligence officer in the 17th Airborne’s HQ, considered Raff a “miserable monster” but conceded, “Despite his queer quirks of character, Raff was a terrific combat leader.”

Indeed, in December 1944 when the 17th Airborne was rushed to Belgium to help stem the tide of the Germans’ Ardennes offensive, Raff earned a reputation for his unruffled professionalism. McCoid later admitted the combat effectiveness of “Raff’s Ruffians” stood above “the less imaginative performances” of the division’s other infantry regiments. But it came at a cost.

When withdrawn from the front in mid-February 1945, the Ruffians had suffered more than one-third of the division’s 2,000 casualties. But after the cauldron of the Ardennes many of Raff’s critics begrudgingly admitted his methods had merit.

As Raff’s jeep continued down the flight line, his men grumbled while struggling to attach the heavy equipment Raff insisted they carry. He wanted them ready to fight when they landed, and that meant jumping with radios, mortars and 31-pound machine guns on their person.

Private Rexford Bass, who’d be jumping in the first serial with Raff, was one such unhappy soul. With a chest-mounted satchel for his belt-fed .30-caliber machine gun clipped into each shoulder of his parachute harness, he had to waddle toward the plane, as the contraption was so long that it dragged the ground. Private Glenn Lawson strapped on a leg bag containing his 60 mm mortar. He would lower it on a 20-foot suspension line after his chute opened to dangle below him during descent.

The complaints were tempered by the realization Raff was right. In a few hours the Ruffians would jump into Germany in the vanguard of Operation Varsity, the airdrop to support the Allied crossing of the Rhine River. And they were expecting heavy resistance.

That same morning British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s 21 Army Group was assaulting the Rhine with five divisions abreast. As part of that effort two airborne divisions—the British 6th and the American 17th—were to be dropped inland and form a bridgehead.

The 507th’s objective was to seize the high ground of Diersfordt Forest, from where it was feared German artillery would wreak havoc on the river crossing. Raff and the 694 troopers of 1st Battalion would be departing in 46 aircraft, while the regiment’s two other battalions were flying in serials out of airfield A-79. The fourth serial would drop the 464th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion to provide heavier firepower.

Their collective destination would be Drop Zone W (DZ W) an egg-shaped area of open farmland hugging the eastern edge of the forest. At just over a mile inland from the Rhine’s east bank, they would be landing closest to the river while the rest of the division established the bridgehead’s right-flank perimeter farther inland.

Colonel Joel Couch, a veteran pilot who’d flown multiple combat airdrops, would be piloting the lead aircraft. He wagered Raff a case of champagne that he’d drop the Ruffians right on target. Raff, who suspected everyone of incompetence, took the bet.

At 0725 hours Couch’s aircraft roared down the runway, and within minutes the other 45 planes of the first serial had climbed into the clear blue sky.

They rendezvoused over Wavre, Belgium, with the largest Allied airborne armada of the war: more than 1,500 powered aircraft and 1,300 gliders escorted by close to 500 British and American fighters. The phalanxes of aircraft carrying the two airborne divisions took more than three hours to pass a single point on the ground.

As the aircraft neared Germany, the terrain below shifted from colorful villages and idyllic farms to an ominous gray landscape of shell craters and burnt fields. Olive-drab convoys congested the roads, bringing forward tanks, engineering equipment, sections of pontoon bridges and countless other supplies.

The pilots, pushing closer to the Rhine, passed back the 10-minute warning. The jumpmasters in turn stood to face the men, bellowing, “Get readddyyyyy!”

“Get ready!” the men shouted back. After hooking up their chutes’ static lines and conducting a final equipment check, the jumpers crowded toward the open cargo door, waiting to surge forward.

Over the steady pitch of the engines the troopers heard the muffled crumps of exploding flak getting closer. From the far side of the river German anti-aircraft gunners targeted the incoming transports. Several near misses burst between the planes, showering their thin skin with what sounded like gravel. The concussions jarred the aircraft and buffeted the men inside.

“Rhine!” yelled the jumpmasters. Pilots toggled the jump light to red—the two-minute warning.

In the lead aircraft Couch was having difficulty spotting his checkpoints as he crossed over the Rhine. Smoke from the river assault had drifted inland, reducing visibility. As Couch descended to 600 feet, Raff braced himself in the open cargo door, scanning the farm fields flashing past. Behind him the troopers felt the plane reduce speed to 110 mph. They were anxious and wanted out—anything was better than being tossed around in the back of a flak magnet. Couch flipped the jump light to green at 0948.

“Let’s go!” shouted Raff, launching himself out the door. Keying off Couch’s plane, the other pilots flipped on their jump signals as well.

The sky filled with chutes, and within a few minutes Raff’s 1st Battalion had crashed to earth in Germany. A murky haze obscured landmarks, but the irrigation ditches and hedgerows appeared to match the maps they had studied. Officers and sergeants gathered troopers and formed them into squads and platoons as they moved toward the tree line. Raff herded 200 of his men off the DZ. He knew the next serial should be dropping in four minutes, and it was smart to clear out as fast as possible.

Entrenched enemy machine guns opened up on the Americans as they advanced. Squads of troopers went to ground while others bounded forward. The well-rehearsed choreography was simple: Someone was always shooting, and someone was always moving. If everyone did his job, the tactic overwhelmed the enemy by keeping their heads down or making them traverse too quickly to be accurate. It was effective, deadly and exhausting work. The Ruffians swept into the German positions, suffering some casualties, but eliminating the machine guns and capturing their first prisoners.

Raff noticed something was wrong when the planes of the second serial came over. They were flying farther south and dropping troops on the far side of the forest. Map study and information from a POW confirmed pilot Couch had lost the champagne bet: He’d dropped Raff’s 1st Battalion almost a mile and a half off the DZ.

Other troopers realized they’d missed the DZ when they noticed the hazy silhouette of Diersfordt Castle a half-mile to their west. Noted during the planning phase of the operation, the compound was suspected to be a German HQ and was an objective of Raff’s 3rd Battalion.

Having assembled roughly 400 men of the first serial, Raff turned his attention to two immediate targets: the castle and a nearby enemy artillery battery. He understood that seizing these objectives, even with a portion of his troops, would pay off. He wanted to exploit the initial pandemonium; delays would only favor the enemy, giving them time to muster stronger defenses. It was important to keep the Germans reacting to events rather than dictating them.

Since no radio contact had yet been made with the still-organizing 3rd Battalion, Raff gave the job of capturing the castle to 1st Battalion’s Company A. The situation called for improvisation, and they’d be going into the attack. The artillery battery would be tackled by a group of troopers led by Lt. Murray Harvey. It didn’t matter to Raff the enemy guns were in a section of forest assigned to another regiment; the howitzers were firing at troops crossing the Rhine and had to be dealt with.

While Raff reorganized 1st Battalion, C-47s continued to roar over DZ W at 600 feet. Four aircraft in the second serial were hit by anti-aircraft fire, one fatally. A single paratrooper escaped, but the other 17 and all of the aircrew died when the plane plunged into a large stone barn.

The third serial jumped five seconds late, putting dozens of jumpers 500 yards farther east than intended. Among them was Capt. Paschal Fowlkes, an unarmed chaplain, who was shot to death while caught in a tree.

The fourth serial, dropping the Ruffians’ artillery support, arrived overhead at 1003. Three of their 12 howitzers’ chutes malfunctioned, and the massive bundles tumbled through the sky in a tangled mess, thudding into the ground. Useless.

Once on the ground, troopers hugged the furrowed fields. The woods to the north and west sparked with muzzle flashes from dug-in machine guns. Fire poured in from several houses turned into fortified bunkers. Heavy mortars and artillery peppered the DZ.

Small groups of artillerymen fought their way out to their supply bundles and soon had three of their heavy .50-caliber machine guns in action. The methodical chug-chug-chug of the belt-fed machine guns could be heard raking the tree line. Their overwhelming firepower provided essential cover for the crews crawling out to assemble the howitzers. Soon the welcoming boom of friendly artillery could be heard above the fracas as crews leveled their 75 mm howitzers in direct fire on the German positions.

With the Ruffians on DZ W mopping up resistance, Company A prepared to seize the castle complex. After a series of brief skirmishes, including a bloody battle with a German Mark IV tank, the company made a wide flanking move through the woods that drew fire from the castle’s defenders.

Simultaneously, 3rd Battalion had departed the DZ and was advancing toward the castle from the east. With radio contact established, Raff ordered Company A to hold its position and provide covering fire as 3rd Battalion organized for its assault. Raff himself kept moving with the rest of 1st Battalion to establish the regimental command post on the DZ.

Two companies of 3rd Battalion formed a wide arc on the castle’s east side. They used an embankment along the tree line for cover, but as they moved into position, the volume of fire from the castle swelled. A distinct clanking sound could be heard above the cacophony of rifle and machine gun fire. Tanks.

Two panzers rumbled down a narrow, tree-lined road, headed directly for the troopers’ embankment. Rounds from the lead tank sailed in, injuring several troopers. The two tanks were soon put out of action—the first by a well-heaved British Gammon grenade, and the second by a 57 mm round from an M18 recoilless rifle.

With Company A providing mortar and small arms cover, the Ruffians along the embankment launched their attack on the compound’s northeast corner through a section of collapsed wall. Disaster struck as soon as the advancing troopers crossed into the open field. Enemy fire cut down several men, and the assault commander was wounded. The attack stalled, forcing the men to withdraw to the shelter of the berm—they would have to try again.

The battalion commander reorganized his men for a textbook plan: In a coordinated effort one element would unleash fire at the castle, aiming at windows to keep the enemy’s head down; the other element would use the covering fire to maneuver against the northeast corner.

When the second hand of their watches ticked up to 1300, the troopers cut loose. Bullets from rifles and belt-fed machine guns chipped away at the castle’s brick facade. The assaulting troopers surged forward, splashing across the shallow moat and clearing the outer buildings room by room. They ran past the bodies of their buddies who’d died in the first attack. Grenades echoed in the large blockhouse as the attack became a series of individual battles, with troopers scurrying across the complex for cover and shooting at anything not in olive drab. Faced with the paratroopers’ full fury, pockets of defenders started to surrender.

Just before 1530 Raff reported his situation to higher headquarters: He had radio contact with his three battalions, and the initial confusion of the missed drop had been quickly replaced with orderly execution. His men had established a perimeter and set up roadblocks along the southern sector. At least 80 percent of his troops were accounted for, with losses estimated at 99 casualties.

Though the mopping up at Diersfordt Castle was under way, the Americans had taken 300 POWs, while the remaining defenders were buttoned up and no longer posed a threat.

But the Germans were still counterattacking. At least two enemy self-propelled guns clanked their way into the Ruffians’ northern perimeter. As the enemy armor hurled 75 mm shells into the DZ, a forward observer called for fire. Several rounds rattled in, bracketing the tracked vehicles before pulverizing them with direct hits.

Raff, recognizing the potential of an enemy breakthrough, dispatched two companies from 1st Battalion to clear several enemy positions and reinforce the northern perimeter.

After flanking through the woods of Diersfordt Forest, the paratroopers were driven to ground by the rat-tat-tat-tat-tat of two German machine guns dug into the front gardens of two farmhouses. Trenches and foxholes surrounded the emplacement. The farmyard had already been the scene of heavy fighting. Several dead paratroopers—many still in their chutes—were scattered around the farmhouses. From the way some of the bodies were positioned, it appeared at least six of them had been executed.

A Ruffian later recalled the chaos of the swarming attack: “Everywhere was a gray uniform, shoot, run, shoot, throw a grenade.” As the Ruffians overwhelmed the trenches, the Germans retreated, leaving behind their dead and wounded.

With their objectives secured and resistance reduced to minor skirmishes, the Ruffians sent out patrols to sweep the area. One of the patrols found a forward squad from the British 6th Airborne and passed back the good news by radio. In the regimental diary a staff officer confessed the news “[relieved] the feeling that we were all alone on this mission.”

The patrols searched houses and rousted out any occupants. Herding the civilians into holding points was the safest option for all concerned, as it would get them out of the crossfire and ease the minds of punchy troopers wanting their perimeter cleared before sunset. The troopers segregated the civilians from the POWs, whose numbers had swelled to an estimated 700.

As the sun dipped below the horizon, the Ruffians dug in for the night to await morning, when reinforcing Allied tanks—crossing the Rhine on barges and pontoon bridges—were to arrive. In the meantime, Raff’s aggressive leadership had paid off. His regiment had quickly recovered from its missed drop to literally advance through the fog of war and successfully secure their sector.

For the Ruffians, March 24, 1945, was almost over. An American flag flew over Diersfordt Castle, but more objectives and villages remained to be seized before the war was over. They would continue to advance with the 17th Airborne Division, sweeping deeper into Germany to help close the Ruhr Pocket’s northern flank. They ended their campaign as occupation troops in Duisburg, a mere 15 miles upstream from DZ W, where their journey into the Reich had begun.