In late 1926, Lt. Alford Joseph Williams approached the Packard Motor Car Company (Packard) regarding a high-power engine for a special aircraft project. Williams was an officer in the United States Navy and believed that air racing contributed directly to the development of front-line fighter aircraft. The United States had won the Schneider Trophy two out of the last three races, and another win would mean permanent retention of the trophy for the US. However, the US government was no longer interested in supporting a Schneider team.

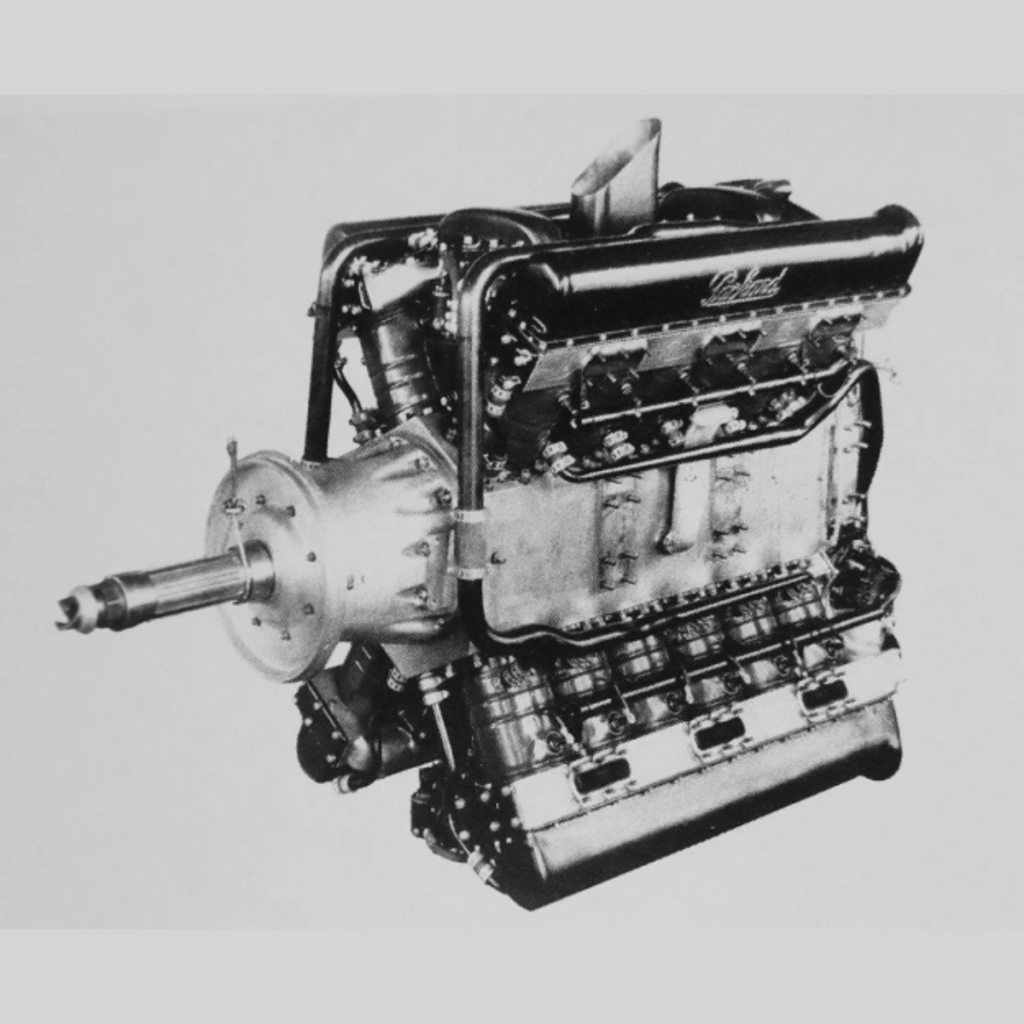

The original Packard X-2775 (1A-2775) was a direct-drive engine installed in the Kirkham-Williams Racer. A housing extended the propeller shaft to better streamline the engine. Two mounting pads were integral with the crankcase, and a third was part of the timing gear cover at the rear of the engine. Note the vertical intake in the center of the upper Vee.

Williams was assembling a group of investors to fund the design and construction of a private racer to participate in the Schneider contest. In addition, the US Navy was willing to indirectly support the efforts of a private entry. With the Navy willing to cover the development of the engine, Packard agreed to build a powerful engine for Williams’ Schneider racer. On 9 February 1927, the US government officially announced that it would not be sending a team to compete in the 1927 Schneider race, held in Venice, Italy. On 24 March 1927, it was announced that a private group of patriotic sportsmen had formed the Mercury Flying Corporation (MFC) to build a racer for the Schneider Trophy contest that would be piloted by Williams. The aircraft was built by the Kirkham Products Corporation and was known as the Kirkham-Williams Racer.

Packard had started the initial design work on the engine shortly after agreeing to its construction, even though a contract had not been issued. Once the Navy had the funds, Contract No. 3224 was issued to cover the engine’s cost. To speed development of the powerful engine, Packard combined components of two proven V-1500 engines to create a new 24-cylinder engine. The new engine was designated the Packard 1A-2775, but it was also commonly referred to by its Navy designation of X-2775.

The X-2775’s hexagonal, barrel-type crankcase, timing gear drive and housing, connecting rods, and crankshaft. Note the walls inside of the crankcase, and the crankshaft’s large cheeks that acted as main journals.

The Packard X-2775 was designed by Lionel Melville Woolson. The engine was arranged in an X configuration, with four banks of six cylinders. The upper and lower banks retained the 60-degree bank angle of the V-1500. This left 120-degree bank angles on the sides of the engine. As many V-1500 components were used as possible, including pistons, the basic valve gear, and the induction system. At the front of the X-2775, the propeller shaft ran in an extended housing and was coupled directly to the crankshaft, without any gear reduction. The extended housing allowed for a more streamlined engine installation.

A single-piece, cast aluminum, hexagonal, barrel-type crankcase was used. Two engine mounting pads were provided on each side of the crankcase, and a third pad was incorporated into the side of the timing gear housing, which mounted to the rear of the engine. The crankcase was designed to support landing gear or floats connected to the forwardmost engine mounting pad. Seven integrally cast partitions were provided inside the crankcase. The partitions were hollow at their center and were used to support the crankshaft. The seven single-piece main bearings were made of Babbitt-lined steel rings, shrunk into the crankcase’s partitions, and retained by screws from the outer side of the flanged partition. The partitions had a series of holes around their periphery that allowed for the internal flow of oil as well as enabled assembly of the engine’s connecting rods.

Upper image is the valve port arrangement that was integral with the valve and camshaft housing. The drawing includes the ports to circulate hot exhaust gases around the intake manifold to ensure fuel vaporization. The lower image is the unique valve spring arrangement designed by Lionel Woolson. Helically-twisted guides (left) held the seven small springs (center) to make the complete spring set (right).

The crankshaft was positioned about 1.5 in (38 mm) above the crankcase’s centerline and had six crankpins. The crankshaft’s cheeks acted as main journals. The cheeks were perfectly circular and were 7.75 in (197 mm) in diameter. This design increased the main bearing surface area to support the engine’s power but kept the crankshaft the same overall length as the crankshaft used on the V-1500 engine. A longer crankshaft would result in a longer and heavier engine, as well as necessitating the design and manufacture of new valve housings and camshafts. At 161 lb (73 kg), the crankshaft was around twice the weight of the crankshaft used in the V-1500 engine. The X-2775’s crankshaft was inserted through the center of the crankcase for assembly.

Each connecting rod assembly was made up of a master rod and three articulated rods. The end cap, with its two bosses for the articulating rods, was attached to the master rod by four studs. The articulated rods had forked ends that connected to the blade bosses on the master rod. The forked end of each articulated rod was tapped and secured to the master rod by a threaded rod pin. Once assembled, two bolts passed through the connecting rod assembly to further secure its two halves and also secured the pins of the articulated rods. To accommodate the crankshaft being approximately 1.5 in (38 mm) above center in the crankcase, the lower articulated rods were 1.5 in (38 mm) longer than the other rods. When the engine was viewed from the rear, the master rods were attached to pistons in the upper left cylinder bank.

Sectional view of the X-2775 engine. The engine mount is depicted on the left, and the landing gear or float mount is on the right. Note the spark plug position. The revised engine had provisions for four spark plugs—two on each side of the cylinder.

Individual steel cylinders of welded construction with welded-on steel water jackets were mounted to the crankcase via 10 studs. The cylinder’s combustion chamber had machined valve ports and was welded to the top of the cylinder barrel. Five studs protruded above each cylinder’s combustion chamber and were used to secure the cast aluminum valve and camshaft housing. Each bank of six cylinders had a single valve and camshaft housing.

Each cylinder had two intake and two exhaust valves. The valves were arranged so that one intake and one exhaust valve were on the Vee side of the cylinder, and the pairing was duplicated on the other side of the cylinder. The valve and camshaft housing collected the exhaust gases from two adjacent cylinders and expelled it out one of three exhaust ports. The valve and camshaft housing also had an integral intake manifold that fed three cylinders. The valves for each cylinder bank were actuated by a single overhead camshaft driven by an inclined shaft at the rear of the engine. The two inclined shafts for each Vee engine section were driven by a vertical shaft geared to the crankshaft. The lower vertical shaft was extended to drive one fuel, one water, and four oil pumps. The shafts were enclosed in the timing gear housing that mounted to the back of the engine. The valve covers of the lower cylinders also formed sumps for engine oil collection. Oil was circulated through various passageways in addition to the hollow crankshaft and hollow camshaft. The exhaust valve had a hollow stem for oil cooling.

The valve springs were designed by Woolson and were a unique design. Rather than the valve stem passing through the center of one or two valve springs, a set of seven smaller springs encircled the valve stem. Each of the seven springs was mounted on a guide, and the set was contained in a special retainer. The seven spring guides were given a slight helical twist. The special valve spring set distributed the spring load evenly around the valve stem, reduced the likelihood of a valve failure due to a spring breaking, prevented valve springs from setting, and also rotated the valve during engine operation. The valve rotation was one revolution for about every 40 revolutions of the crankshaft.

Front and rear views of the original X-2775 illustrate that the engine was narrow but rather tall. The ring around the propeller shaft was a fixed attachment point for the engine cowling.

Each cylinder’s combustion chamber had a flat roof with a spark plug on each side of the cylinder. The spark plugs were fired by a battery-powered ignition system via four distributors driven at the rear of the engine. Two distributors were positioned behind each 60-degree cylinder bank Vee. In each cylinder, one spark plug was fired by an upper distributor, and one spark plug was fired by a lower distributor. Separate induction systems were positioned in the upper and lower cylinder Vees. Each system consisted of a central inlet that branched into a forward and rear section. Each section had a carburetor and fed six cylinders. This gave the engine a total of four carburetors—two in each upper and lower vee. Control rods linked the carburetors to the distributors so that ignition timing was altered with throttle position. A port in the valve and camshaft housing fed exhaust gases through a jacket surrounding the manifold to which the carburetor mounted. The exhaust gases heated the intake manifold to better vaporize the incoming fuel charge.

Packard’s V-1500 engine had a 5.375 in (137 mm) bore and a 5.5 in (140 mm) stroke. The X-2775 had the same 5.375 in (137 mm) bore, but the stroke was shortened to 5.0 in (127 mm). However, the three articulated connecting rods had a slightly longer stroke of 5.125 in (130 mm). Each of the six cylinders served by a master rod had a displacement of 113.5 cu in (1.86 L), and each of the 18 cylinders served by an articulated rod had a displacement of 116.3 cu in (1.91 L). The total displacement for the engine was 2,774 cu in (45.5 L). The X-2775 produced a maximum of 1,250 hp (932 kW) at 2,780 rpm and was rated for 1,200 hp (895 kW) at 2,600 rpm. At 2,000 rpm, the engine had an output of 800 hp (597 kW). The X-2775 was 77.5 in (1.97 m) long, 28.3 in wide (.72 m), and 45.2 in (1.15 m) tall. The weight of the initial X-2775 was 1,402 lb (636 kg).

The second X-2775 incorporated a Roots-type supercharger driven from the propeller shaft. Difficulty was encountered with fuel metering since the carburetors were positioned on the pressure side of the supercharger. The supercharged engine was never installed in an aircraft.

The X-2775 engine was completed in June 1927 and subsequently passed an acceptance test, which involved the engine running continuously at full throttle for one hour. Williams was involved with testing the X-2775 at Packard to gain experience with its operation. The engine was then shipped out for installation in the Kirkham-Williams Racer, which was finished in late July. The racer and the X-2775 made their first flight on 25 August. Despite achieving speeds around 270 mph (435 km/h), the racer had issues that could not be resolved in time for the Schneider Trophy contest, scheduled to start on 23 September. The Kirkham-Williams Racer was subsequently converted to a land plane, and Williams flew the aircraft over a 3 km (1.9 mi) course unofficially timed at 322.42 mph (518.88 km/h) on 6 November 1927. However, that speed was with the wind, and Williams later stated that the true speed was around 287 mph (462 km/h). Higher speeds had been anticipated. The aircraft was then shipped to the Navy Aircraft Factory (NAF) at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Around late June 1927, rumors indicated that the Schneider competition would be faster than the Kirkham-Williams Racer. As a result, the Navy added a second X-2775 engine to its existing contract with Packard. The second engine incorporated a supercharger for increased power output. In the span of 10 weeks, Packard had designed, constructed, and tested the new engine. The second X-2775 engine was, again, direct drive. However, the propeller shaft also drove a Roots-style supercharger with three rotors (impellers). A central rotor was coaxial with the propeller shaft, and it interacted with an upper and lower rotor that supplied forced induction to the respective upper and lower cylinder banks. For the upper Vee, air was brought in the right side of the supercharger housing and exited the left side, flowing into a manifold routed between the upper cylinder banks. For the lower Vee, the flow was reversed—entering the left side of the supercharger and exiting the right. The supercharged X-2775 weighed around 1,635 lb (742 kg).

Because of the very tight development schedule, the rotors were given generous clearances. This reduced the amount of boost the supercharger generated to only 3.78 psi (.26 bar), which increased the X-2775’s output to 1,300 hp (696 kW) at 2,700 rpm. Tighter rotor tolerances would yield 4.72 psi (.33 bar) of boost and 1,500 hp (1,119 kW) at 2,700 rpm. However, it is not known if improved rotors were ever built. Although completed around August 1927, the supercharged engine was never installed in the Kirkham-Williams Racer.

The first X-2775 engine was reworked with a propeller gear reduction, new cylinders, new valve housings, and a new induction system. This engine was installed in the Williams Mercury Racer. (NASM image)

The Navy felt that adding a propeller gear reduction to the engine would be more beneficial than the supercharger. To this end, the unsupercharged engine was removed from the Kirkham-Williams Racer as the aircraft was disassembled in the NAF around early 1928. The engine was returned to Packard for modifications. A new aircraft, the Williams Mercury Racer, was to be built, and the first X-2775 engine with the new gear reduction and other modifications would power the machine.

A planetary (epicyclic) gear reduction was built by the Allison Engineering Company in Indianapolis, Indiana. This gear reduction mounted to the front of the engine and turned the propeller at .677 crankshaft speed. Other modifications to the X-2775 included using cylinders and valve housings from an inverted 3A-1500 (the latest V-1500) engine and revising the induction and ignition systems.

The new cylinders increased the engine’s compression (most likely to 7.0 to 1) and had provisions for two spark plugs on both sides of the cylinder. Still, only two spark plugs were used, with one on each side of the cylinder. The new induction was a ram-air system with inlets right behind the propeller. The air flowed into a manifold located deep in the cylinder bank’s Vee. Two groups of two carburetors were mounted to the manifold. Each carburetor distributed the air/fuel mixture to a short manifold that fed three cylinders. The revised ignition system used two magnetos and did away with battery power. The magnetos were mounted to the rear of the engine and driven from the main timing gear. The improved X-2775 was occasionally referred to as the 2A-2775, but it mostly retained the same 1A-2775 Packard designation of its original configuration. The geared X-2775 produced 1,300 hp (969 kW) at 2,700 rpm and weighed around 1,513 lb (686 kg). The gear reduction added about 3 in (76 mm) to the engine, resulting in an overall length of 80.5 in (2.04 m). The width was unchanged at 28.3 in (.72 m), but the revised induction system reduced the engine height slightly to 43.25 in (1.10 m).

The revised X-2775 took advantage of ram-air induction. Intakes directly behind the Williams Mercury Racer’s spinner fed air into manifolds at the base of the cylinder Vees. Note the spark plugs on both sides of the cylinders. (NASM image)

The updated X-2775 engine was installed in the Williams Mercury Racer in July 1929. In early August, flight testing was attempted on Chesapeake Bay near the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. While the aircraft was recorded at 106 mph (171 km/h) on the water, it could not lift off. The Williams Mercury Racer was known to be overweight, and there were questions about its float design. The trouble with the racer caused it to be withdrawn from the Schneider Trophy contest, scheduled to start on 6 September in Calshot, England. Later, it was found that the Williams Mercury Racer was some 880 lb (399 kg), or 21%, overweight. Some additional work was done on the aircraft, but no further attempts at flight were made.

Of the original X-2775, Woolson stated that the engine ran for some 30 hours, and at no time was mechanical trouble experienced or any adjustments made. Williams made some comments about the X-2775 losing power, but he otherwise seemed satisfied with the engine and did not report any specific issues. Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Aeronautics David S. Ingalls did not make any negative comments about the engine, but he said Commander Ralph Downs Weyerbacher of the NAF felt that the engine was not satisfactory. However, the basis for Weyerbacher’s opinion has not been found.

There were essentially no X-2775 test engines. Only two engines were made, and the second engine was never installed in any aircraft. The very first X-2775 built was installed in the Kirkham-Williams Racer, and the majority of the issues encounter seemed to come from the aircraft, and not the engine. This scenario repeated itself two years later with the Williams Mercury Racer. The X-2775 did not have any issues propelling the updated racer at over 100 mph (161 km/h) on the surface of the water, but it was the aircraft that was overweight and unable to take flight. If the engine were significantly flawed, it would not have survived its time in the Kirkham-Williams Racer, have been subsequently modified, and then installed in the Williams Mercury Racer. This same engine, Serial No. 1, was preserved and is in storage at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Packard offered to build additional X-2775 engines for anyone willing to spend $35,000, but no orders were placed. In the late 1930s, Packard investigated building an updated X-2775 as the 2A-2775. The 2A-2775 was listed as a supercharged engine that produced 1,900 hp (1,417 kW) at 2,800 rpm and weighed 1,722 lb (781 kg). Some sources indicate the engine was built, although no pictures or test data have been found.

Top view of the X-2775 illustrates the two sets of two carburetors, with each carburetor attached to a manifold for three cylinders. The intake manifold can be seen running under the carburetors. (NASM image)