In early 1968 a Soviet submarine sailed from its base in Kamchatka in the far east of Russia to take up a station in the Pacific. From that position it could, if ordered by Moscow, launch the three nuclear missiles it carried to strike American bases in Hawaii.

Within days the submarine, with 98 officers and sailors aboard, disappeared. It failed to transmit scheduled radio messages, and the Soviet Navy became alarmed. The K-129, a reliable sub of the Golf class II which had conducted missions in the Pacific for eight years, would never be heard from again.

Soviet ships, submarines, and airplanes were dispatched to search vast stretches of the ocean, which, of course, drew the attention of the US Navy. It became apparent that a Soviet submarine had suffered a catastrophe. And it seemed that commanders in Moscow had no idea where it was.

The CIA

The Americans, however, had picked up some clues. And over the course of the next few years, the Central Intelligence Agency, the CIA, would engage in one of the most elaborate and audacious operations it ever attempted. It would build an enormous ship designed for one highly unusual task. They would assemble a crew sworn to secrecy. Then weave a plausible and very public cover story with the help of the legendarily eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes.

Six years after a disaster sent the Soviet submarine to the bottom, the CIA would sail its huge ship to the spot. They’d reach down three miles, and try to snatch the Soviet sub. At the end of the mission, the CIA would obtain only part of the sub. And the Americans would also conduct a solemn burial at sea service for the remains of Soviet sailors found in the raised wreckage.

Clues and a Secret Search

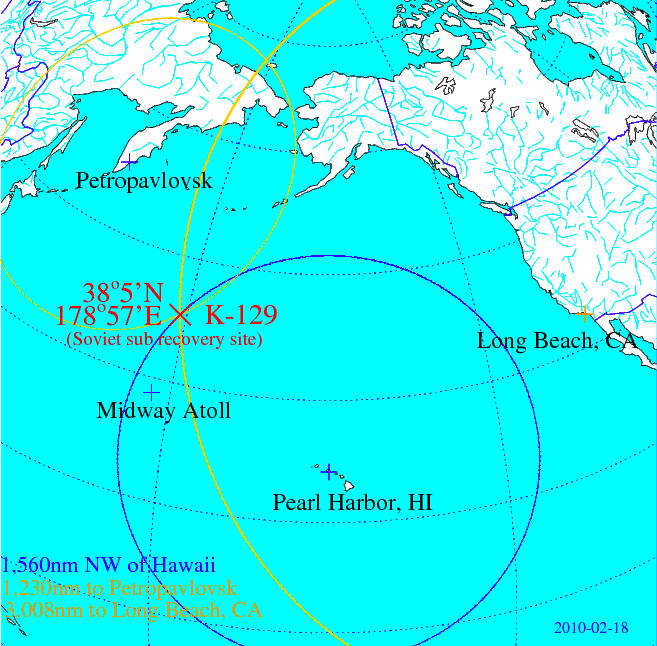

Thanks to a network of underwater sensors designed to capture the sounds of Soviet submarines, the US Navy had detected sounds of the K-129’s destruction on March 8, 1968. By calculating how long it took for the sounds of apparent explosions to reach various listening posts, the Americans were able to narrow down the location where the sub went down.

The US Navy happened to have a submarine, the USS Halibut, which had been repurposed from a missile launching ship to a deep water surveillance sub. The Halibut could tow a deep water vehicle that could search the ocean floor. This could be done without anyone on the surface knowing a search was taking place.

Using the Halibut’s capabilities, the Americans managed to locate – and photograph – the wreck of the Soviet submarine on the ocean floor. It did this in more than 16,000 feet of water in the summer of 1968.

The mosaic of photos studied by American intelligence analysts revealed something astounding. It appeared one of the tubes which held a Soviet nuclear missile was intact.

The CIA wanted to grab that missile and examine it. And the National Security Agency, the highly secret American codebreakers, wanted to obtain any cryptographic material that would be aboard the submarine.

Planning for a wildly ambitious mission, code named Project Azorian within the CIA, began.

A Fake Cover Story and a Real Ship

The photos of the wrecked Russian sub obtained by American intelligence in the summer of 1968 showed that the aft section of the sub had broken off. But approximately 130 feet of the sub was intact, though badly damaged. CIA and US Navy scientists began to calculate how the wrecked sub could be lifted off the seabed.

It was decided that the best method would be to use what’s known as a drill string. This was a series of connecting pipes, that would reach down from a surface ship. A specially made structure designed to grab the sub’s wreckage would be lowered down on the drill string. This would secure the submarine. Then the capture vehicle, with the sub in its grasp, would be raised upward.

This entire project had to be conducted secretly, of course. First of all, seizing another country’s sunken ship violated international law. And the consequences could go beyond diplomatic complaints. It was assumed the Soviet Navy would not stand by idly while the US Navy tried to raise the wrecked submarine.

The Covert Operation

The solution was to build what appeared to be a civilian ship for the job. It had to be massive, and with a peculiar custom design that included retractable doors on the bottom of its hull.

The wrecked submarine would be lifted, unseen, into a gigantic bay in the ship. Then it could be examined by American intelligence officials.

The cost of the project, of course, would be astronomical. And there also had to be a way to explain an enormous and peculiar ship taking up a stationary position for a week or two in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

The solution was a grandiose cover story. The new ship, it would be publicly announced, was a commercial venture. It was to conduct a deep sea mining operation which was the latest brainchild of Howard Hughes. When the CIA approached him, the notoriously eccentric Hughes was happy to help.

Hughes Glomar Explorer

Construction on the ship, which would be called the Hughes Glomar Explorer, began in May 1971 at a shipyard in Pennsylvania. It was launched in late 1972. The ship was more than 600 feet long. To ensure the opening in the bottom of the ship (known as a “moon pool”) was large enough to accommodate the capture vehicle with the Soviet sub in its grasp, the ship had a beam of 115 feet. That made it too wide to travel to the Pacific Ocean via the Panama Canal.

After some testing in the Atlantic Ocean, the ship sailed around the tip of South America to California. It was fitted out at a facility of the Summa Corporation, which was owned by Howard Hughes. Truckloads of classified equipment was needed to complete the mission. This included such items that could stabilize and restore paper which had been submerged, was loaded onto the ship.

The cover story that the Hughes Glomar Explorer had been built as a deep sea mining ship was accepted by the press and the public. The cover story proved ingenious. An enormous deep sea mining ship seemed like the kind of peculiar project that would be run by Howard Hughes.

In California, the capture vehicle, a large contraption wielding claws which had been specially designed to grab the wreckage of the Soviet sub, was placed inside the large surface ship. The cover story was that the equipment was some sort of giant vacuum. This would pull pieces of manganese from the ocean floor. And it was technology being kept secret for commercial reasons.

The Mission at Sea

In late June 1974 the ship sailed off into the Pacific. But only after a shipboard reception at which employees of Howard Hughes sipped champagne and sliced a large cake. The cover story was working.

Soon after the Hughes Glomar Explorer reached its intended position over the wreck of the K-129 in July 1974 it received an unexpected visitor. A British merchant vessel, the Bel Hudson, approached and radioed that it needed medical help for a crew member who was believed to have suffered a heart attack.

The CIA had planned for this eventuality. The Americans responded in a friendly manner and offered to send the ship’s doctor to the British vessel.

The British ship asked what the American ship’s business was. The Americans said they were testing experimental deep sea mining equipment. It was hoped the Soviets were listening in to the radio traffic, as it would bolster the mission’s cover story.

The American doctor examined the British sailor on board the Bel Hudson, and then the sailor was taken to the Hughes Glomar Explorer for X-Rays in its onboard clinic. The crew of the American ship made sure the visitors never saw any classified equipment. The ships parted amicably, and the CIA assumed the encounter had bolstered the cover story.

Other visitors to the recovery site were far less friendly. A Soviet Navy ship, the Chazhma arrived on July 18, 1974. The Chazma, a guided missile support ship, was 459 feet long and carried a helicopter.

An Unwelcome Visitor

CIA personnel became wary that the helicopter from the Chazhma might try to land on the helipad on the stern of the Hughes Glomar Explorer. Crates of equipment were piled onto the helipad to make that impossible.

The Chazhma came within a mile of the American ship. Its helicopter took off and approached. Crew members, including some CIA security people, assembled on the deck in case the Soviets tried to land any personnel on the deck.

The helicopter, with men onboard taking photographs of the American ship, flew in circles in a harassing manner. But eventually the helicopter returned to the Chazhma. Another flight by the helicopter occurred later in the day, but the Soviets did not try to board the American ship.

The Soviets, via radio, inquired what the ship’s business was. The Americans responded that they were testing experimental deep sea mining equipment. The Soviets soon sailed off, headed back to its home port (which had also been the home port of the ill-fated K-129).

A few days later, on July 22, a 155-foot Soviet salvage tug, the SB-10, approached the Hughes Glomar Explorer. The Soviet boat began a series of harassing moves, sailing within 500 feet of the large American ship. The SB-10 then sailed to about a mile away, where it stayed for days, conducting surveillance.

While the recovery team kept lowering the drill string, the Soviets kept watch. But there wasn’t much they could see. US Navy divers were part of the Hughes Glomar Explorer crew, in case they needed to watch for Soviet divers nosing about.

Lifting the Soviet Sub

On August 1, 1974, the recovery vehicle, with the wreckage of the K-129 in its jaws, slowly began to be lifted from more than 16,000 feet under the sea. On August 4 there was a shudder throughout the ship. It seemed that a large amount of weight on the end of the drill string had fallen away. The view through closed circuit TV monitors confirmed that most of the hull of the K-129 had broken away and fallen back to the ocean floor.

Only the most forward 38 feet of the hull of the K-129 remained in the grasp of the recovery vehicle. That meant the coveted Soviet nuclear missile, and any cryptological material, had been scattered back to the ocean floor.

During the following days the lifting continued. At times the Soviet SB-10 tug came close to the American ship. Finally, after 13 days of surveillance, the SB-10 sailed off. As it departed, the wreck of the Soviet sub was getting close to being lifted inside the Hughes Glomar Explorer. While they didn’t know it, the Soviets had witnessed one of their subs being lifted off the ocean floor.

Rising From the Deep

On August 6, 1974, the 38-foot bow section of the K-129 was brought up into the hull of the Hughes Glomar Explorer. There had been a fear that the wreck would be highly radioactive, but that wasn’t the case. The crumpled section of hull was drained of sea water, and American intelligence officials began inspecting it.

The Hughes Glomar Explorer, after sending coded messages back to the Summa Corporation headquarters in California, began its return voyage on August 9, the same day President Richard Nixon’s resignation took effect. After he took the oath of office, it is assumed the new president, Gerald Ford, was made aware of the CIA’s operation in the depths of the Pacific.

Accounts of what was found in the crumpled wreck of the submarine are purposely vague, but it is known that the bodies of several Soviet sailors, including some that were badly mangled and two that were nearly intact, were located.

The Evidence

The bell of the K-129 was located, as were some paper documents, which were hurried to the technicians tasked with paper conservation. Other items of interest were saved for further study. Othertems thought to be of no intelligence value were broken up to be disposed of at sea.

In the following days the Hughes Glomar Explorer sailed to a position about 500 miles from Hawaii. At that spot some items were placed in crates to move to an intelligence facility somewhere in the western United States. Other items were jettisoned.

And the bodies of the six Soviet sailors, three of whom could be identified, were buried at sea by the Americans on September 4, 1974. The ceremony, which included an honour guard and the placement of Soviet naval flags over the bodies, was carefully scripted and filmed. It was assumed that some day the video of the service would be given to the Soviets.

Legacy of Project Azorian

The Project Azorian mission concluded and the enormous ship returned to its home berth in California in late September 1974.

Not surprisingly, it’s not known how useful any of the material obtained from the K-129 was to the CIA or the NSA. It’s safe to assume that the large section that broke away contained most of what the operation hoped to obtain. So in that sense the mission had failed.

There have been suggestions over the years that the story of the submarine breaking up while being raised is itself a cover story meant to obscure how much intelligence was actually obtained.

However, the story of the sub breaking up while being raised seems to be true. It is known that the CIA began planning for a second mission, code named Project Matador, which would seek to raise the rest of the sub.

Astonishing public revelations about the raising of the wrecked submarine began in February 1975 with a story in the Los Angeles Times. In a bizarre series of events, a break-in at the offices of Summa Corporation the previous summer meant that the CIA saw a need to inform some top officers in the Los Angeles Police Department of the company’s links to the secret project.

It is believed the initial leaks about Project Azorian came from, of all places, local police sources.

A large story in the New York Times in March 1975 made the project so widely known that the CIA scrapped any further plans to return to the wreck site. Project Matador was shut down.

The Story Takes a Twist

Debates about the funding of the project, as well as the ownership of the Hughes Glomar Explorer, continued. The large ship was eventually officially acquired by the US Navy, and later by the National Science Foundation. It was sold to private owners who operated it as an oil drilling ship. The big ship was scrapped in 2015.

An unusual sequel to the CIA’s deep ocean operation occurred in 1992. The director of the CIA at the time, Robert Gates, presented the film of the burial at sea of the Soviet sailors to Russian president Boris Yeltsin as a gesture of good will.

In 1993, a panel of Russian scientists presented a report to President Yeltsin which claimed that the Americans had successfully recovered two nuclear warheads from the wreck of the K-129. When the New York Times reported on that in an article on June 20, 1993, the CIA, of course, refused to comment.

There is even a dispute about what sent the K-129 to the bottom. The Soviets always claimed that an American submarine collided with it, causing catastrophic damage. The Americans have always denied that. And the CIA seemed to believe the K-129 was fatally damaged by an explosion of propellant for the submarine’s missiles.

An article about Project Azorian written in 1985 for an in-house CIA journal was declassified in 2010. The document the CIA released is highly redacted, and does not address some of the questions that have lingered for decades. How much of the Soviet submarine and its sunken secrets were raised may always remain a mystery.